“The wealth of African countries does not have to do with money, it is their culture and their traditions. Therefore it is so important that we process traditional culture in our work and at the same time show that we are open for external influences.” Abdoulaye Konaté

Rob Perrée on the Malian artist Abdoulaye Konaté

L’Oisseau Rouge, 2016.

(first published October 3, 2017)

ABDOULAYE KONATE

“Artists have to be socially engaged.”

The Balla Fasséké Kouyaté Conservatory, near Bamako, the Malian capital. Photograph: Banning Eyre.

The subtitle of this article is a quote of Abdoulaye Konaté (1953), an artist from Mali. In 2004 he founded Balla Fasséké Kouyaté Conservatory, an institute in Bamako dedicated to ‘arts et metiers’, in particular fine art, theatre, dance and music. It is more than an art academy, a theatre school or a regular conservatory. It is an institution that wants to build on the long cultural tradition of the country; it wants to create jobs for their students and it wants them to serve the cultural heritage of their country by staying there. There is room for a maximum of 300 students. About 80 teachers are involved. Konaté not only thinks that “it is important that (students) understand the techniques and concepts behind their own culture,” he also underlines the importance of staying in touch with and being informed about global developments in the arts. Therefore the institute invites artists and musicians from other countries to give classes, workshops and presentations. Foreign ‘teachers’ are responsible for about 20% of the program.

In 2012 a military coup took place in Mali. Since then they talk in Bamako in terms of: ‘before the war’ and ‘after the war’. Tourism collapsed, the economy – weak in the first place – went more down the hill, and the north of the country is still kind of a mine field where thousands of UN military people try to keep the peace. The war did not take Konaté off track; he is even more convinced that “arts are a key weapon for peace”. Retired now, he still is backing and supporting ‘his’ institute in all possible ways.

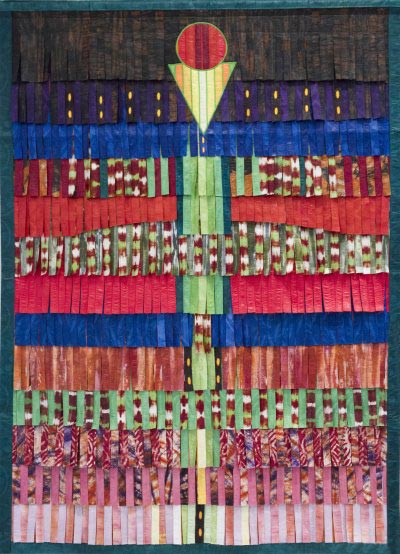

Composition avec Cercle et Trangle, 2017.

It is perhaps hard to believe, but next to his activities as an educator and director he managed to have a very successful career as an artist. Especially the last five years his work is shown in galleries and museums all over the world.

Although originally educated in Bamako and Havana as a painter and sculpture, in the 90’s he decided to use fabric (cotton) for his art. “Fabric is my palette. I paint with fabric.” He is influenced by the layered clothes of the traditional Senufo musicians. For a number of reasons it is not so strange that the Senufo musicians were the basis of the change in his work. First of all, music permanently fills the space as he works in his studio. More important perhaps is another reason. One of his basic principles is to make art in which the culture of his country meets global cultures. The music of Mali is the ultimate ‘export product’ of his country. Cotton is one of the lifelines of the economy. The production of it is still according to a long African tradition: women dye the cotton, men work with it. His work fits the Malian culture also because in big parts of Africa textiles are still means of communication. To communicate with art is an important goal for Konaté.

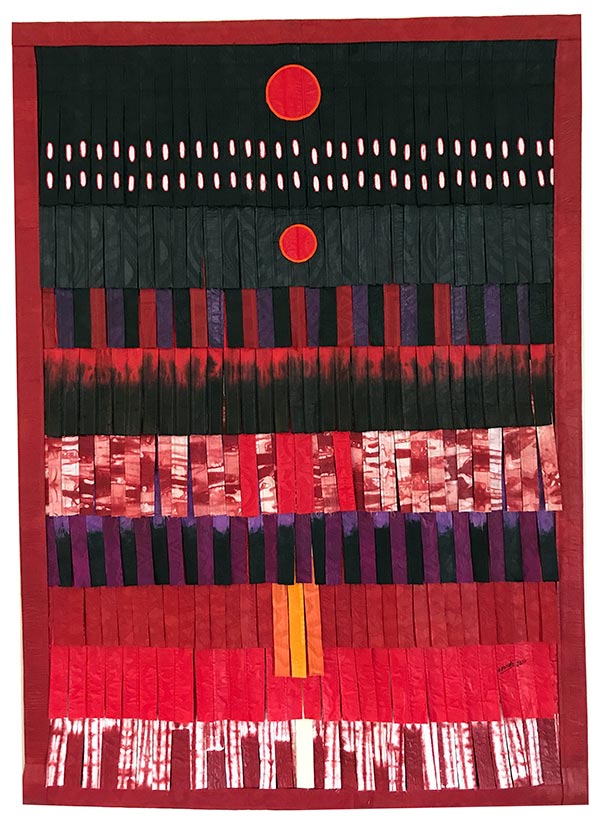

His works look like wall tapestries. Most of the time they are composed of layered, hand-embroidered cotton ribbons. The colors play a big role. He works with several colors and these colors are stitched in many shades. The choice of color depends not only on the composition he has in mind – “compositions that remind me of carefully composed scores “– also the symbolic meaning can direct his choice. If he uses red it is possible that he refers to violence, white has a more positive connotation, black refers to death, indigo is the national color, symbolizing the country itself.

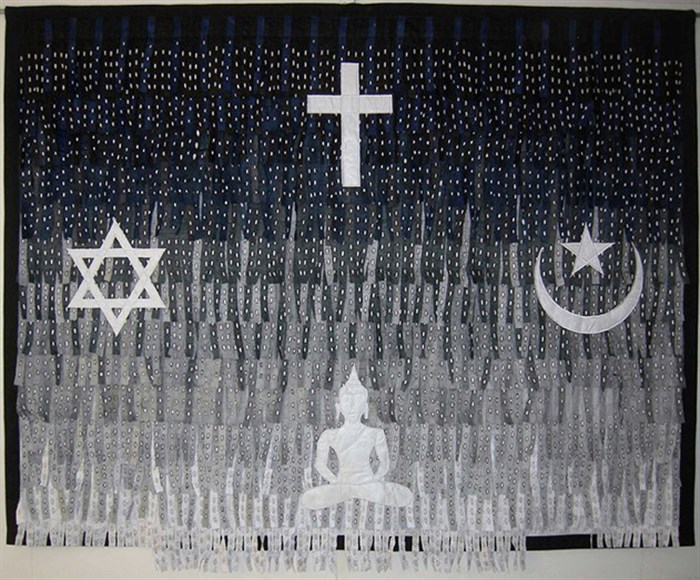

Tolerance Religieuse, 2013.

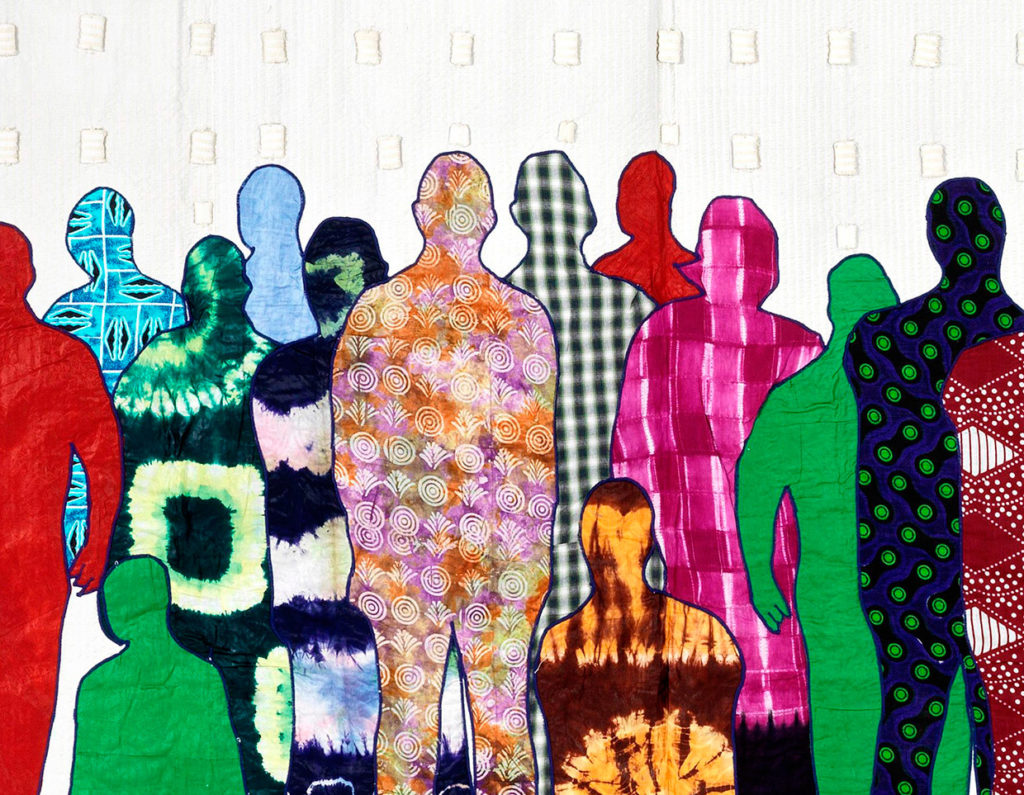

Biometric Generation No 5, 2008.

His works can be figurative, abstract or a combination of both. In his figurative works he shows his ‘engagement’. He reacts to all kind of problems and issues, inside and outside of his country: war, immigration, social welfare, abuse of power, terrorist attacks, AIDS and the lack of awareness of it , etc. “To empty his head”, as he calls it, he wants to tell stories about these problems. Stories need people, living creatures and symbols, more than forms. He is very serious about that part of his artistic practice. “Artists have to be socially engaged.” He strongly believes for instance that “art is a key weapon for peace”. In 2002 the Africa Cup started in Mali. He covered the whole soccer field with an enormous work – 6000 square meters – that promoted AIDS awareness. With ‘The Pencil’ (2015) he reacts on the Charlie Hebdo murders; religious fanaticism he berates in ‘Tolerance Religieuse’, an in gray- and black shades composed work from 2013. In 2008 he made a series of works on immigration. He calls them ‘Biometric Generation’ because the destiny of immigrants depends on the outcome of biometric measurements of eyes and fingerprints.

Deux Cercles Rouge, 2017.

In his abstract works he connects African symbolism with Western Modernism. Several critics use the expression ‘symphony of colors’ to describe these works. A symphony of shades is perhaps more accurate. These works are more than compositions of and with color. The layering makes them sculptural, tactile, Tapies-like and creates a playground for light and shadow. It is not much of an exaggeration to stipulate that these works translate his fascination for Rembrandt.

Homme Nature II, 2015.

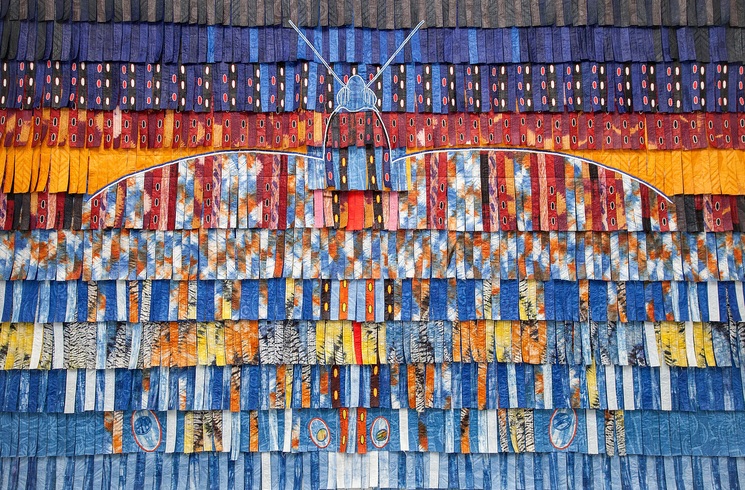

Le Papillon Blue, 2016.

Often works that look abstract on first sight hold details that add inevitably narrative elements to it. “Because I have to do it on that very moment”, he says, almost as an excuse. Sometimes he adds these elements also as a way of involving aspects or characteristics of the country that commissioned the work. At the bottom of ‘Homme Nature II’ (2015) the issue of the vulnerable environment breaks through the abstraction; in ‘Le Papillon Blue’ (2016) shine the outlines through of a butterfly as a symbol of fragility, but also as symbol of transformation; the crown in ‘Power and Religion’ (2011) refers to the questionable or at least ambiguous relation between religions (cross and crescent) and power and the layered from-white-to-gray-to-black ribbons refer to the plumage of the Guinea Fowl, a bird that features in many traditional African stories.

*

According to Abdoulay Konaté African art still has a backlog on art of the West, not because of a lack of quality, but because most African countries don’t have the publicity machinery and the infrastructure that Western countries take for granted. “The wealth of African countries does not have to do with money, it is their culture and their traditions. Therefore it is so important that we process traditional culture in our work and at the same time show that we are open for external influences.” By doing that, artists like Konaté show implicitly that the boundaries between art and craft are ambiguous, not more than a Western concept.

Power and Religion, 2011.

The works of Konaté are often compared to the tapestries of El Anatsui. The Ghanese artist transforms found materials – mostly bottle-tops or bottle caps – “into large shimmering forms by assembling elements into vibrant patterns with unique visual impact.” He also intertwines traditional culture with Western elements. He also works with local people to put his works together. However, his work focuses mainly on the visual impact, the aesthetic richness of poor material. Unlike Konaté his ‘engagement’ is indirect. He does not want to convey a message.

Since Abdoulaye Konaté retired from his director job, he has more time for his art projects. Together with his 4 assistants (male) and the company around the corner of his studio in Bamako that dyes cotton (female), facilitated by his laptop (the designs are developed on the screen), he will create more tapestries that impress because of their formal beauty but also because of the stories and the references they contain.