When and how do we address subjects as race and nationality in the global contemporary art context? The Canon should never be cast in stone. The current times call for new definitions and wording that are accepted and intelligible by all working in the arts internationally. Wording that reflects our time, is decolonized, inclusive and self-evident of our global context.

Is contemporary African Art a hype? Sasha Dees ‘feeds’ the conversation.

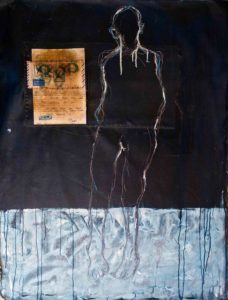

Onyis Martin, Untitled, 2016.

Contemporary African Art a hype?

or

Don’t believe the hype.

Somerset House, location of 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, London.

On my way to London Frieze and 1:54 Art Fairs, Rob Perrée (editor-in-chief of Africanah.org) asked me to write about the state of African Art. Perrée, just back from a month-long stay in France, shared with me his discussions in Paris on the subject. Artists he met in Paris felt African Art is just the latest hype in the “Western commercial market.” 1:54 Art Fair (London / New York), in its third year, which features artists from the continent, was mentioned as proof of the hype, as in their view there is little to no entry to “Western not commercial spaces,” hence the need for dedicated platforms.

Addis Fine Art booth at 1:54 Art Fair, London, 2016

Power, and with it ownership, is not something people give up voluntarily or even share. This month the annual Art Power 100 by the British art magazine Art Review* came out. On the list are artists Zanele Muholi (95) and William Kentridge (62); founding artistic director of Raw Material Company, Koyo Kouoh (75); and Okwui Enwezor (20), director Haus der Kunst Munich and curator of the 2015 Venice Biennale. The four in the list indeed deserve their place and respect in general. That said 4 vs. 37 from Europe and 26 from United States is definitely skimpy in terms of power and Enwezor in actuality is counted as from the United States (the list uses nationalities). Kouoh and Enwezor however are excellent examples of curators that open many doors and have given artists from the African continent greater visibility in not commercial spaces internationally in the past two decades.

The collectors on the list are known to have an international vision rather than exclusively buying works from white European** artists. Is that hype or something that has been going on for a longer time? Is it reflective of other collectors? What happens with the art in the collections and how visible are the artists in those collections to others? How much influence do collectors have in what we the audience see?

Georges Adeagbo installs his work, 2016, Photo: Stephan Kohler.

Two recent exhibitions I saw immediately came to mind. The first, Wir nennen es Ludwig is a retrospective of 40 years of Museum Ludwig (on till January 2017). In 1976 collectors Peter & Irene Ludwig donated their collection and founded Museum Ludwig. They have always collected from international artists, not hindered by any political position in their country. Case in point, they kept collecting Cuban artists during the boycott (as seen in the exhibition). Also in this exhibition, Georges Adeagbo installed part of his “Explorer and Explorers Facing the history of Exploration” (bought by the museum in 2003) throughout the museum in dialogue with works of Joseph Beuys. The international vision of Peter & Irene Ludwig is set in stone in the bylaws of the museum and applies to future purchases by the museum. The other, a solo exhibit by Dinh Q. Le: The Colony presented by ArtAngel in London, draws works primarily from collector Han Nefkens (H+F Collection) who also has participated in the comission of this project. Nefkens purchased international contemporary art with the express purpose of giving it to museums on long-term loan. As Nefkens explains, “For me it’s about much, much more than owning a work of art: it’s about sharing a vision with other people.”

Do other people in power on the list have an international gaze and vision? During the London Frieze I was invited for a breakfast to honor Prospect P4 Triennial hosted by Victoria Miro Gallery. I meet multimedia artist Syowia Kyambi, in London for her project at Serpentine Gallery.*** Serpentine’s director is no less than Art Power 100 number one, Hans Ulrich Obrist. Kyambi lives and works in Nairobi, Kenya and is a widely-presented, international multimedia artist. No hyperbole, her calendar at the moment shows her work being presented in India, Germany, Zimbabwe and Ireland.

Syowia Kyambi, WoMen, Fräulein, Damsel & Me, 2014.

Kyambi is making her work on her terms on her turf. Yes, she goes to places where artists want to be seen, but she clearly chooses to work and live in Nairobi which feeds her artistic urgency. Kyambi leaves her space only to collaborate with others as an equal partner. Meeting her provided a window into the future that I hope to see become reality and a reason to believe that a future of equality instead of otherness can be.

Living and working internationally, I prefer to write about art, artists, the work they make and its meaning in this time in this context. Only if the work calls for it do I talk about a specific location or the ethnic background of the artist. Getting an assignment to write about the state of African Art has proven to be challenging: I write and rewrite and rewrite again.

Myriam Mihindou, Terre cicatricée / wounded soil (ongoing).

What is African Art? What do I compare African Art to? Western Art? Asian Art? Pacific Art? What do these terms mean in the world today? I believe we should leave these old definitions and wording behind in the 20th century. In talking about African Art in the current times do I address William Kentridge as William Kentridge, Jewish, South African, African, white, African-born, or of European descent and Okwui Enwezor as Okwui Enwezor, Igbo, Nigerian, American, black, African-born or of African descent? When and how do we address subjects as race and nationality in the global contemporary art context? Canon should never be cast in stone. The current times call for new definitions and wording that are accepted and intelligible by all working in the arts internationally. Wording that reflects our time, is decolonized, inclusive and self-evident of our global context.

It also affirms my belief that the pressing question is not what is the state of “African Art” or any other “Otherness Art”. The pressing questions are: What is the definition of Contemporary Art? And should anyone have the exclusive right to even define it?

Within all the confusion I like to keep things simple and inclusive so I use the definition: “Contemporary Art is art produced at the present period in time.” It personally guarantees me walking into any contemporary art exhibition with an open wondrous mind without judgment. Better yet, it’s a definition that has no owner and therefore can be used in a global context.

Emo de Medeiros, Vodunaut, 2015.

This October, Okwui Enwezor opened the exhibition Postwar: Art between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1946-1965 in Haus der Kunst (14.10.16 — 26.03.17). Hans den Hartog Jager wrote a review for the Dutch daily newspaper NRC.**** The headline of his article reads: “The western view of art is no longer tenable”. At the end of reviewing the exhibition he concludes: “The exhibition aims to show the overarching power of art around the world, Alle Menschen werden Bruder, by showing that artists everywhere touch at the same time on the same phenomena. Postwar indeed counters the theoretical perspective of the West as the center of all major new artistic developments emphatically confirmed by practice and shows that artistic innovation and quirkiness is not exclusively a Western phenomenon.”

An open door to some white Europeans, this is still a new perspective to many others. To that point in his last paragraph he gives words to the confused state white Europeans and Americans are in: “Only, the exhibition fails to formulate new criteria. This exhibition that convincingly shows that the exclusive western view of art is no longer tenable, should at least give a hint on what new ways in which we, with such different background, can view art that comes from such different cultures. Enwezor and his followers clearly think that is a step too far: in fact, you can argue that the criteria used in the exhibition (realism, abstraction, modernism) push the innovative story back in the old western standard.”

Hartog’s last paragraph reflects how difficult it is to really understand and implement the consequences of a no longer tenable western view of art. Hartog points out the question: how do we push the innovative story globally? It would be interesting to see how, after Munich, Enwezor’s exhibition would be received when shown in Nairobi, Teheran or Beijing. For theorists to explore questions as: what is the definition of avant-garde art in different locations, in different contexts. However Enwezor’s exhibition shows a standard of global equality, in his view of art. It confirms that there is no exclusive western view of art and standard because of showing the innovative story using realism, abstraction and modernism. No matter that it might be easy and safe to do so in Munich, Enwezor and his followers actually have set some new criteria: 1. Contemporary Art is not exclusively made, owned or defined by white Europeans. 2. White Europeans can no longer exclusively set standards, decide on definitions, develop theories and archive history.

Ajarb Bernard Ategwa, Untitled, 2016.

Is white Europe and North America capable to make the necessary transition into the global equality? Are we willing to decolonize and question our way of thinking and behavior, our institutions, our funding systems, our educational systems? Are we willing and able to make the needed changes and reform ourselves before our old systems crumble and fall apart?

The global world is an irreversible fact. We live and work in an incredibly exciting time, as we never have been this internationally connected as people. Yet, right now more often than not the starting point for conversations by white Europeans is still that those who are not-Europeans and white Europeans are seen as different, but this is not necessarily so. These times call for critical thinking and theory by open-minded global scholars and critics of all races and nationalities that reflect on differences starting first from equality and similarities. In doing so we might discover the riches that come with that.