The work of M2 is sited (or at least plays a part) in the culture of the city; it is produced as a response to the urban and as a result contributes to producing city life. In this case, the future of art may well be urban. However, if this is to be the case, I would argue that art’s role relies in its ability to not only depict everyday life but to also disturb it – to give it new meaning and purpose. The work of M2 achieves this.

Craig Halliday on the Maasai Mbili Artists’ Collective.

Maasai Mbili Artists’ Collective: The city and contemporary art

“The future of art is not artistic, but urban” declared Henri Lefebvre.(1) While the field of contemporary art cannot be reduced to what happens in the cities of the world today the phenomenon of urbanisation (the most important transformation occurring in Africa (2) is influential in contemporary art practice. Artists create new relations and understandings to urban living, culture, art and city life. This short article examines the work of the artists’ collective ‘Maasai Mbili’ whose practice is deeply connected to their perceived, conceived and lived experience of “slum” life in Kibera – one of Africa’s largest informal settlements in Kenya’s capital city Nairobi.

What is Maasai Mbili?

Maasai Mbili (M2) (3) was founded in 2001 by Otieno Gomba and Otieno Kota. The pair began by selling novel hand-painted signs along Kibera drive, before acquiring a permanent site in 2003.(4) This became the M2 Art-centre; serving as a studio cum gallery and a juncture for many creatives and artists in the area. The M2 Art-centre was a pioneering visual art space in Kibera; initiating opportunities for participation, collaboration, teaching and socialisation – as well as providing a space to work. Today there are approximately 20 members. (5) Painting is at the heart of M2’s artistic practice – some artists continue sign-writing. However M2 also venture into community outreach projects, conceptual work, fashion, film, mixed media, music, photography and sculpture. The work they create, along with the artists, traverse local, national and global art worlds.(6)

Unsurprisingly, as was the need for such a space, the M2 art-centre attracted many artists – most of whom come from this informal settlement. Consequently, M2 has a continuous and authentic relation with the neighbourhood and its people – remaining the most significant artists’ collective in Kibera (7). Though spend a day at this centre and you will notice another element – its positioning in community life. With doors always open, countless members of the public drop by M2 daily – some discuss problems and seek advice, others socialise, and for some a moments respite is treasured. All however experience the art of M2, in some form or other, and it is evident that this art-centre is a valued cultural space in the community.

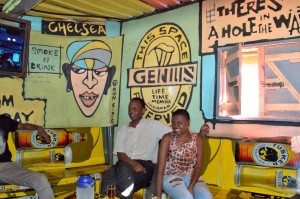

However the art-centre is only one story, or perhaps better phrased one location, of this collective. A short walk from their art space you come across their “second studio” – a local bar selling the illicit home-brewed spirit Changaa. It is here where some artists come for “art supplies” (Changaa) which helps to “kufungua Kichwa” (open the head). While there may be a link between artistic inspiration, heightened creativity, and the use of alcohol, this “second studio” is also a rousing social space – stories are told, opinions shared, quarrels settled (though sometimes made) and concepts conceived. It is easy to see how this space becomes a fitting extension to the M2 art-centre. Though there is an additional space which is central to this story – perhaps a ‘third studio’ – where community life is played. This space is Kibera. There is a certain juxtaposition of beauty and ugliness found here. Nevertheless, however one may characterise Kibera, the home of M2, it is certainly never dull or sterile.

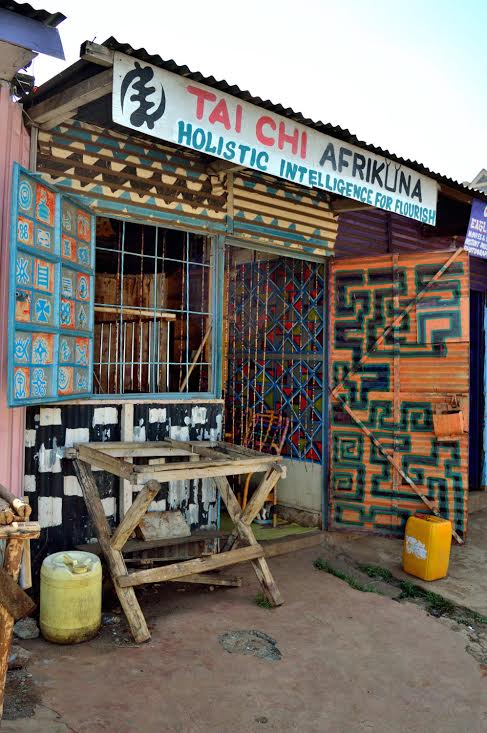

Sign painting in Kibera

It is these three sites which make M2; a collective of artists who yearn for a creatively profound existence and express this through diverse art forms. However, while the art may move from Kibera (or as they call it “the ghetto”) it remains deeply rooted in its social, political and cultural realities. The result is distinctive artwork that provides a critical perspective and commentary – told through their own intelligent and ingenious visual language – concerning this neighbourhood of Nairobi. M2 is characteristically different from Nairobi’s larger and well-resourced art-centres. (8) M2 is a community, with a convincing family feeling and impression of belonging – perhaps strengthened due to its independence from donor funding. As such self-sufficiency is paramount, which requires trust and co-operation between members. Everyday life in Kibera is demanding, it can be relentless and unforgiving. Choosing the life of an artist is gutsy – though perhaps it chooses you. For these artists this often means going through periods of financial strain. It is during these times that the sense of family is most evident. Despite hardships M2 has survived when others art spaces have fallen.

“Bringing the streets to the gallery and the gallery to the streets”

Moving through Kibera the commercial work of sign-painting is still practiced and visible. (9) The scope of imagery and styles demonstrate the encounter between modern life, commodity, form and artistic imagination. It is this creative practice which informs the development of artistic styles and philosophy at M2.

Sign painting in Kibera

Sign painting in Kibera

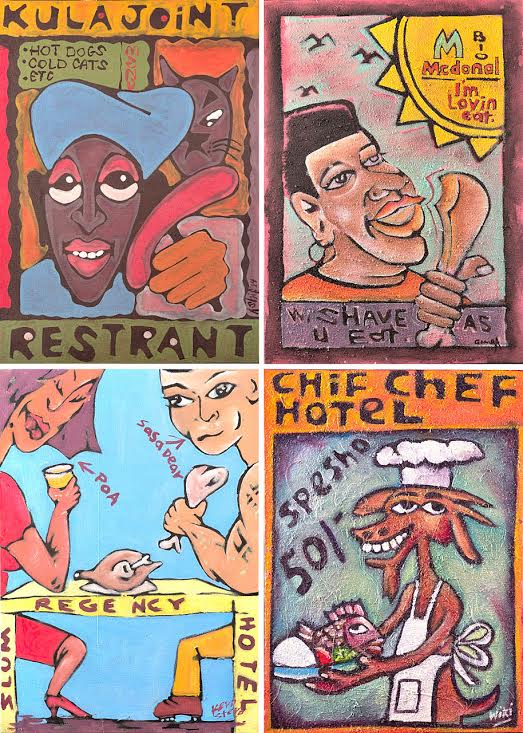

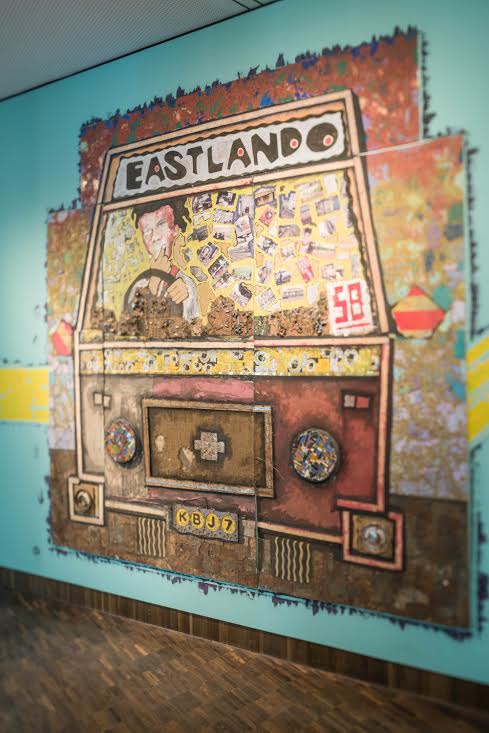

In the work of M2 artists (Gomba, Stero, Opondo and Malamba) elements of text and the flat imagery typical of sign-painting is continued and incorporated into paintings on board, metal chests and canvas. The narrative portrays “the ghetto” through a socio-political lens; text reinforces the imagery – though words are deliberately misspelt. For Gomba this conveys the local slang, perhaps that of Sheng (10), which he sees as “a kind of poetry”. (11) However, the misspelling also references the semi-literate population. Such imagery did not initially sit comfortably in Nairobi’s galleries. Gomba recalls M2’s first exhibition in 2004: “the reception was like this is not art, you can’t put text on paintings”. Today however, these characteristics and references to Kibera (that are incorporated in art forms beyond painting) create work recognisably M2 – a style which they self-describe as “Ghetto Art” or “Street Art”. At times this work is created in the ‘slum’ – for example through the practice of sign-writing for local businesses, the creation of public murals, performance work reclaiming public space, or artistic explorations based on the lives of Kibera’s resident. However, work also travels outside the ‘slum’ into gallery spaces, creating a new audience and aesthetic experience. The late George (Ashif) Malamba (12) described this as “bringing the streets to the gallery and the gallery to the streets”. As such, there is a dynamism to M2’s art practice, an iterative cycle between the street and gallery, one that continually informs and re-informs the other.

From top left clockwise: artwork by Ashif, Gomba, Opondo and Stero. Photo courtesy: Circle Art Gallery.

“You will not pass a day in Kibera without seeing or experiencing something that you can put in a painting”

An undeniable influence for M2 is the characteristics and nuances of Kibera life. Speaking of this, Stero says “A big inspiration for me is noise. Here, in Kibera, they talk and talk, everything is humorous, even when it’s serious.” This inspiration is evident in Stero’s ‘Daily Kibera’ painting series (13) which “talks about what the media doesn’t want to talk about or the things that the media misses”. Stero’s positive representation of everyday life – what may seem mundane or non-sensationalist – is a reflection of the artist’s own experiences and also his almost ethnographic study of Kibera’s residents. His work celebrates everyday occurrences – vendors in the street, friends socialising, people in the bar, games being played, music and dancing. Since 2014 Stero has also been working on a project chronicling the lives of idlers through a satirical NGO called ‘Jobless Corner Campus’, which fights for their rights of idleness. This project – which begins life in the community and later moves to galleries – looks into the emotional wellbeing of idlers (an ‘indicator’ rarely used by development organisations) and questions who the really benefits from the ‘NGO business’.

Kevo Stero at work.

Kevo Stero at work.

Artist Otieno Rabala is not a sign-writer. In 1993, while working as a security guard for Nairobi’s top art gallery, the director bought his work. From then Rabala took art seriously. He joined M2 after befriending Gomba and Kota in 2003 – introducing them to selling work at sites across Nairobi. He says “I get inspired by what is happening in the streets. You will not pass a day in Kibera without seeing or experiencing something that you can put in a painting.” While the stimulus of Kibera is evident, Rabala’s work is split between his representation of family life up-country and that of the metropolis of Nairobi. It is this juxtaposition which leads the artist to question the rural/urban divide and the qualities of life available in each place.

The artist Gomba uses his art to “show what is coming out of Kibera, to show it is happening, it is alive, the vibrancy, and the humour”. While filled with wit, his work also highlights socio-political issues. For instance, the painting series ‘Vote for Mai Self’ seemingly attack personality politics, questioning who you vote for and why. Speaking of another series ‘Save Our Soles’ Gomba says “I would walk around the street and find many used soles, just thrown away. For me they represented human souls.” Gomba incorporated these into his work – which, through a humorous tone, empathised with those downtrodden or less fortunate. He says “whether it is a lost soul, an abused soul, or whatever, it should have a chance of a new life or beginning.” Like Gomba, other artists at M2 (such as Chakara) also re-use found materials – generally what other people see as waste – creating artworks directly from the environment in which they live. A newer generation of M2 artists also contribute their own style – such as Anitah Kavochy who creates portraits in pen and sometimes paint using a style she calls ‘scribbling’; or performance and installation work of Tola.

While M2 members persue their art practice individually, some of their most notable work has come from collaborations (between members, institutions and artists outside of M2 (14). An early example was a public sculpture – Tree of Life – created in 2006 from used materials and installed along Kibera Drive. (15) When travelling further afield M2 continue to creatively and aesthetically reveal aspects of urban culture. For instance, at Donau festival M2 created a life size installation of a Kibera street corner (constructing a pub, shop, and gallery); the exhibition ‘Karibu Mtaa’ (Welcome to the Neighbourhood) saw mixed media artworks referencing characteristics of different neighbourhoods in Nairobi; the show ‘Warosho’ (backstreet) saw paintings, in the form of signs, investigate the meanings and origin of place names from across Nairobi. (16) M2’s continuous exploration of the urban – using the city and their experience of “the ghetto” as a reference point – creates a truthfulness and refreshing perspective of urban life and culture; particularly one which the media regularly portrays negatively or through stereotypes.

Mixed media work from the exhibition ‘Karibu-Mataa’. Courtesy: Uebersee Museum, Bremen

“We want the community to feel that they are just as much a part of us as we are of them”

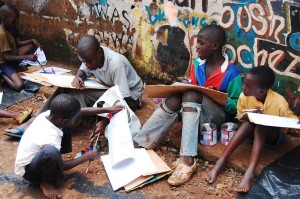

M2 began working with the community in 2005, offering art classes to children – which continue today on an ad-hoc basis. This work was strengthened through partnerships with organisations like Harambee Arts. (17) These efforts are significant as teaching art in school is generally de-emphasised. Many young people have discovered and grown their talent in art thanks to M2. For instance, the young artist Saviour Omondi was able to realise his artistic abilities at M2 – and has since become somewhat a sensation. (18)

It is perhaps the community work that M2 did following the 2007/08 post-election violence that they are most renowned for. Gomba recalls this period saying “I came to my studio and looked at my pieces and I felt I am cheating the world. Inside here [The M2 Art-centre] it was calm and peaceful. But outside there were ruins, people angry, kids traumatised. So at that time we used art as a healing tool.” M2 member Solo 7 (Solomon Muyundo) had already begun painting hundreds of peace slogans, such as ‘PEACE WANTED ALIVE’ and ‘KEEP PEACE’, all over Kibera. Shortly after this M2 developed the project ‘Art4Peace’ – running children’s art workshops and mural painting along Kibera drive and in burnt out buildings. The project re-humanised these spaces through colour, imagery and text which was intrinsic to peacebuilding efforts. The process of art was therapy for children who were traumatised. Rabala recollects the Art4Peace project saying “Through their art children were discussing their possibilities and hopes. Even the parents saw that the work we were doing was something that could bring peace and harmony.” These initiatives were covered widely in the media (19) and cemented the artists into community life. Residents who had been curious before, though were never too sure as to what these artists did, now saw M2 as role models in society.

Saviour Omondi, outside M2 art centre. Photo courtesy: Sanaamtani.

Children Art Workshop outside M2 art centre. Photo courtesy: Harambee Arts..

Writing of Keep Peace by Solo.

A more recent example of community involvement is the project ‘Chokora Wear’. (20) Stero describes it as “a conceptual art piece that deals with fashion and identity and how these are constructed internally and externally”. The project works with film makers, models, photographers, visual artists, and tailors from the community – where shows are performed before moving into gallery spaces. Speaking of community participation Gomba says “if you involve the community then they get to know what you are doing. Many artists just paint in their studios, which doesn’t involve their community. M2 is different in the fact that we are very much community based, we want the community to feel that they are just as much a part of us as we are of them.”

M2’s community art projects have been successful due to the fact that they are built on a foundation of knowledge about the community and stem from the community members themselves. Their work has pursued goals of education and awareness raising, peace and reconciliation, art education and youth empowerment – providing new ways of creative community development. The work of M2 does not simply exist in public space, but instead they have worked towards creating a public and as such can be seen as playing vital roles in generating a heightened understanding and appreciation among the local populace to art’s value.

“Being an artist is a life sentence and we are serving it”

What role an artist has, or plays, in society is always an intriguing question. In the book ‘Artist the Ruler’ the Ugandan poet and novelist Okot p’Bitek speaks of artists as “the imaginative creators of their time, who form the consciousness of their time. They respond deeply and intuitively to what is happening, what has happened and what will happen”. (21) Artists from M2 clearly share an element of this. Likewise, at times, they are evidently agents of creative social change. Though these artists are modest when speaking about their role in society. For instance, an artist according to Mbuthia is “someone who doesn’t live in the system. But you suffer in this role”. Similarly Stero states “I think the first role is to suffer, because you notice everything. You know the artist is always awake, looking around, seeing and understanding what is happening all the time.” This constant observer/reporter position was described by Ashif who stated “I think as an artist it is much more like being a journalist. It is connecting yourself to the people around you and all over the world.” Rabala adds there is also an element of generating ideas for society saying “the role is to make people think independently…to make people create their own way of seeing things and thinking”. These artists clearly see their role beyond that of someone who creates or gives creative expression to works of art. It is a role they have consciously chosen and as Gomba says “being an artist is a life sentence and we are serving it”.

Understanding the collective’s artistic practice

M2 and their work encapsulate many of the tropes often associated with contemporary ‘African art’ – such as ‘self-taught’, ‘naïve art’, ‘transnational’, ‘Jua Kali’ or ‘popular art’. However, in this short essay I have chosen to avoid using these terms. This is partly because such language has been used to denote quite different things by various people. These strict terms are also laden with weaknesses often ignoring the fluidity of artists and their work. John Picton describes such classification as the ‘Jack-in-the-Box syndrome; where the artist is thrust in a certain category, ready to jump out and dance only when the art historian springs the catch’. (22) As a result, such terminology would hinder understanding M2’s artistic practice.

Rather, this essay has presented the artists and their work through their own voice. From the Daily Kibera paintings and Jobless Corner installations by Stero; the Save our Souls and Vote for Mai Self paintings of Gomba; Rabala’s paintings juxtaposing the urban with the rural; the collective’s work in the community and their representation of Nairobi at international venues; or the artists continuous practice of sign-writing. The broad spectrum of work created by M2 is united by their association to the “slum” and their critical and creative understanding of the city. The artists portray their vision through their own “street” or “ghetto” art language which is closely related to contemporary social and political issues, with a healthy dose of humour.

Sign painting in Kibera

The work of M2 is sited (or at least plays a part) in the culture of the city; it is produced as a response to the urban and as a result contributes to producing city life. In this case, the future of art may well be urban. However, if this is to be the case, I would argue that art’s role relies in its ability to not only depict everyday life but to also disturb it – to give it new meaning and purpose. The work of M2 achieves this. Their art practice resists a seemingly ever encroaching danger of cultural homogenisation – experienced in globalised cities where there is a risk of everyone leading a uniformed urban existence. The artists’ activity of M2 – which is carried out in the everyday space of the street and then once again in conventional art spaces – provide alternative models of thinking and knowing when it comes to urban living. Their artwork offers new perspectives and understandings of street, or ‘ghetto’, life. They and their work, after all, embody visual representations and the voice of Kibera. In essence these artists celebrate their “right to the city”(23) in which we have the freedom, through collective action, to transform ourselves and our urban environment.

Notes:

-

See Lefebvre, 1996, ‘Writings on cities’, Blackwell, Cambridge, MA

-

See World Bank report, 2013, – ‘Harnessing Urbanization to End Poverty and Boost Prosperity in Africa’, Africa region sustainable development series. Washington DC https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/16657/815460WP0Afric00Box379851B00PUBLIC0.pdf?sequence=1

-

The name Maasai Mbili means Two Maasai in Kiswahili. Initially Gomba and Kota would dress as Maasai (although neither were) to attract customers to their signwriting – hence the name.

-

The group began by renting a space which before was a notorious drinking spot. Though soon the owner decided to put the premises up for sale. M2 held an art exhibition and managed to raise half of the funds required. Some well-wishers were able to support M2 with the remaining funds to buy the premises. Over the years Maasai Mbili have continued to develop the site. In 2011 the space was restructured, the building which was once made mainly from corrugated iron sheets is now brick. M2 now hope to create a second floor to their art-centre.

-

At the Core of Maasai Mbili is a group of consistent members who in a sense hold the collective together. These include Otieno Gomba, Otieno Kennedy Rabala, Kevin Iringa (Kevo Stero) and Mbuthia Maina. Some early members have moved from the art centre – such as Otieno Kota who works remotely in various studio settings across Nairobi and Wycliffe (Wiki) Opondo who now works from a studio at Kuona Trust.

-

Maasai Mbili have exhibited extensively in Nairobi as well as internationally. To date, M2 have worked, or exhibited, in, Austria, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Norway, Sweden and the United States of America.

-

Other visual art spaces in Kibera include ‘Uweza Art Gallery’ (established in 2013) which nurtures young artists and provides a space for them to create and market their work. The current art teacher at Uweza is Faith Atieno, who was a member of M2 in 2011. Another space is ‘Nyota Art Gallery’ (established in 2015) which works creatively with children and young people from Kibera.

-

For example spaces such as ‘Kuona Trust’ and ‘The GoDown Art-centre’ – who to a degree are reliant on donor funding and whose members generally do not come from the community in which these art centres are situated.

-

In Nairobi sign-painting dates back to the early 20th Century. As the city grew so too did the need for inexpensive commercial signs, murals and billboards. Artists specialising in this form of painting and lettering soon emerged. The practice is still continued despite authors, since 1990, speaking of the threat from new digital technologies – which are generally much cheaper than hand painted signs.

10. See ‘Sheng: Language of Empowerment or Disobedience?’ Craig Halliday (2012) – https://web.archive.org/web/20140803191814/http://thinkafricapress.com/kenya/sheng-language-empowerment-or-disobedience

-

When not referenced, quotations come from personal interviews with members of M2, dating from 2010 to 2016.

-

Ashif passed away May 30th, 2015. He is remembered fondly by the Kenyan art community and his home community of Kibera

-

Stero started the series ‘Daily Kibera’ following the post-election violence of 2007/8 and he continues it today. The series is created both on canvas and in the street

-

Sam Hopkins has been a notable collaborator with the collective M2. The collective has also worked extensively with Kuona Trust and Goethe-Institut Nairobi, among others.

-

Unfortunately this public sculpture did not last long. Rabala recalls it being removed by Nairobi City Council – perhaps, he says, they thought it was part of a business constructed without permission.

-

Donau festival is one of Europe’s largest art and culture events in Austria – which M2 attended in 2009. ‘Karibu Mtaa’ (Welcome to the Neighbourhood) was held in 2013 at Ubersee-Museum (Bremen, Germany). Also in Germany, the ‘Warosho’ (backstreet) exhibition took place in 2010 at the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum.

-

Harambee Arts uses art to help those who have suffered trauma caused by violence, illness, poverty, trafficking and other crises. The artists Mbuthia Maina introduced Harambee Arts to Maasai Mbili in 2008 and they have since worked on a number of community projects, which have included running art workshops for children, working with women prisoners and with vulnerable children in school

-

After working at M2 Saviour Omondi started attending Kuona Trust at the weekends. A short interview by Saviour can be found here http://sanaamtaani.org/art/Kunstler-innen/Savoiur%20Omondi.html

-

Even the American ambassador came to visit M2 to thank them for their peace-keeping activities.

-

Chokora is a slang term used to describe street people. The project has had three seasons and in addition to Nairobi, Chokora Wear has also been taken to Austria. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubVMW4areD4

-

P’Bitek, O (1986) – ‘Artist the Ruler. Essays on Art, Culture and Values’, Nairobi: Heinemann. pg.39

-

John Picton, 1999, ‘In Vogue, or The Flavour of the Month: The New Way to Wear Black’, in Olu Oguibe and Okwui Enwezor, eds, Reading the Contemporary: African Art from Theory to the Market Place, Institute of International Visual Arts (INIVA), London; MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, pg. 119

-

See David Harvey, 2008, ‘The Right to the City’, New Left Review 53, September-October