New York is the hometown of art. Also the hometown of Trump. A city that loves art and a president who does not know and does not care about art. He wants to cut art funding completely. These last weeks New York could prove that it does not care about Trump.

Rob Perrée reports about recent art activities in New York

NEW YORK IS CALLING

From Miko Veldkamp to the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair

With more than 300 galleries, more than 10 museums and thousands of artists the chance that you see good art in New York is big. In the last couple of weeks the city had even more to offer: a biennial, 6 art fairs, a film festival and an international literature festival.

It was physically but also mentally impossible to visit all these venues and activities. I have selected a small, promising selection.

.

The Whitney Biennial

The Whitney Biennial has a tradition of controversy. Whatever it shows, critics either love it or hate it. The (guest)curators are always under fire. This time the opening had to be postponed because of an unexpected springtime snowstorm. When the biennial finally opened it seemed to become a ‘normal’ event: a solid show, interesting selection, high quality art, nice variation in the use of media, young and older artists, and a necessary dose of engaged art. All lives seemed to matter. But, looking back, it appeared to be silent before the storm.

It is fair to say that Henry Taylor was playing the leading role in the biennial (the oldest in the US). Because of the amount of works, the huge format of some of them but especially because of the (painful) content and the unique quality of his pieces. Taylor is based in Los Angeles. In most of his paintings his family and friends are featured. Not this time. The most impressive painting for me was of Philando Castile who was killed in his car by a police officer while his girlfriend was behind the wheel and his little kid was on the backseat. The girlfriend filmed the killing. Taylor used rough strokes to paint this shocking incident. A few functional details (eyes, a white hand holding a revolver), hardly any nuances in color. Just the plain facts, so to say. It had a highly confronting effect on me. Form and content reinforced each other.

Henry Taylor, The Times They Aint Changing Fast Enough, 2017.

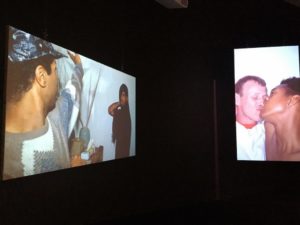

Lyle Ashton Harris presented a remarkable installation: ‘Once (Now) Again’ (2017). A slide work, projected on several screens in a darkened space, of archival images of friends, family members, lovers, landmark events shot between 1986 and1998. A very personal, sometimes touching, documentation of an often turbulent time for gay men (AIDS). Of course it reminded me of ‘The Ballad of Sexual Dependency’ by Nan Goldin, but the way it was presented – qua rhythm and qua interaction between the images – gave the work its own, unique quality. There were some nude images, but they did not cause angry reactions by visitors. However, when I posted a selection out of the images as an Africanah.org post on Facebook, I was forced by the ‘Zuckerberg censor committee’ to remove that one-out-of-five nude image before I could go back to that ‘open’ platform…..

Lyle Ashton Harris, Once (Now) Again, 2017 (detail)

But, none these works caused the commotion. To my surprise it was a painting of Dana Schultz, an artist from Brooklyn. Not because it was stunning – Henry Taylor is a far better painter – but because it was a response to the famous photo of the brutally killed Emmett Till, a southern black child who was – in 1955 – accused of flirting with a white woman. Schultz’ painting is an almost abstract registration of a very shocking moment in black history. The mother of the victim promoted the publication of the photo at that time to show the world what white people did to her son. I don’t know the motives of the artist and of course she should (and perhaps must) have realized how sensitive a subject like that would be, but to ask for the destruction of the painting “because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time” (text of the Open Letter to the curators), was not a very smart and a strongly exaggerated reaction. It was that same conflict that made all the headlines and overshadowed the show.

A pity, because all in all it is a good show.

Dana Schutz, Open Casket, 2016.

Miko Veldkamp

Veldkamp was born in Suriname but he lived almost all of his life in the Netherlands and, since 2014, in the US. First in Baltimore, and now in New York. Some of his works on the internet triggered my curiosity. I decided to do a studio visit. A small loft in an apartment on the Upper West Side.

Miko Veldkamp, Pope Francis and his followers posting selfies, 2016

Miko Veldkamp, The Media on its Way to Baltimore, 2016.

The paintings I saw were small. He assured me that there was no relation between the size of the studio and the size of his paintings: big frames were leaning against the wall, waiting for the next series of work. What I was able to see were scenes that suggested a reality, but never wanted to be realistic. Veldkamp called them products of a mental reality. They are the result of moods and ideas fed by his daily life, the world around him, things he reads and sees. They tell stories, are poems even, with ‘blanks’ in it. The viewer is invited to fill the gaps. The literary titles confuse and help at the same time. Sometimes a work has a political reference (Trump), more often the paintings are like fantasies going out of hand. Veldkamp does not mind inconsistency. His painting style moves between figurative and abstract. Objects, people, urban landscapes are recognizable as such but they are never painted in a precise, detailed way. People are dots of paint, buildings are reduced to contours. He uses a limited amount of colors. Among other things, he does not want to feed the cliché that artists born in a tropical country are characterised by colorful work. In every painting he juxtaposes just a few modest colors.

Some of his works seem to be influenced by folk art painters like Grandma Moses, others remind me of artists like Philip Guston.

Intriguing work that deserves more exposure.

William T. Williams

William T. Williams, Blues Labyrinth, 1991.

Williams (1942) is not a very known African-American artist. He has his own explanation for that fact:

“One of the things I remember most is … people asking me … ‘Why are you making abstraction? It’s not African American art.’ And I would always say, “Well … you tell me what it should look like. Jazz is the most abstract of all music. Music is totally abstract. How can you not say there’s a tradition of abstraction?’ I would talk about quilts, point out that the geometry of quilts is certainly coming out of abstraction. There is this rich tradition; all you have to do is see it and to use it.”

For years he had to fight this prejudice. He chose for abstraction, because it gave him more freedom to experiment. With colors, with forms, with ways of painting. His work is never cold and it does not simply refer to itself. There are personal references integrated: his love for Jazz, for the landscapes of the South of the US and also his love for the patterns used by traditional quilt makers. The titles of his work – Blues Labyrinth, Harlem Angels, Texas Lady etc. – make that all the more clear. Abstraction and narratives can go together.

The exhibition ‘William T. Williams: Things Unknown. Paintings 1968-2017’ in the Rosenfeld Gallery was a wonderful tribute to an ‘unknown’ artist.

We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-1985, Brooklyn Museum

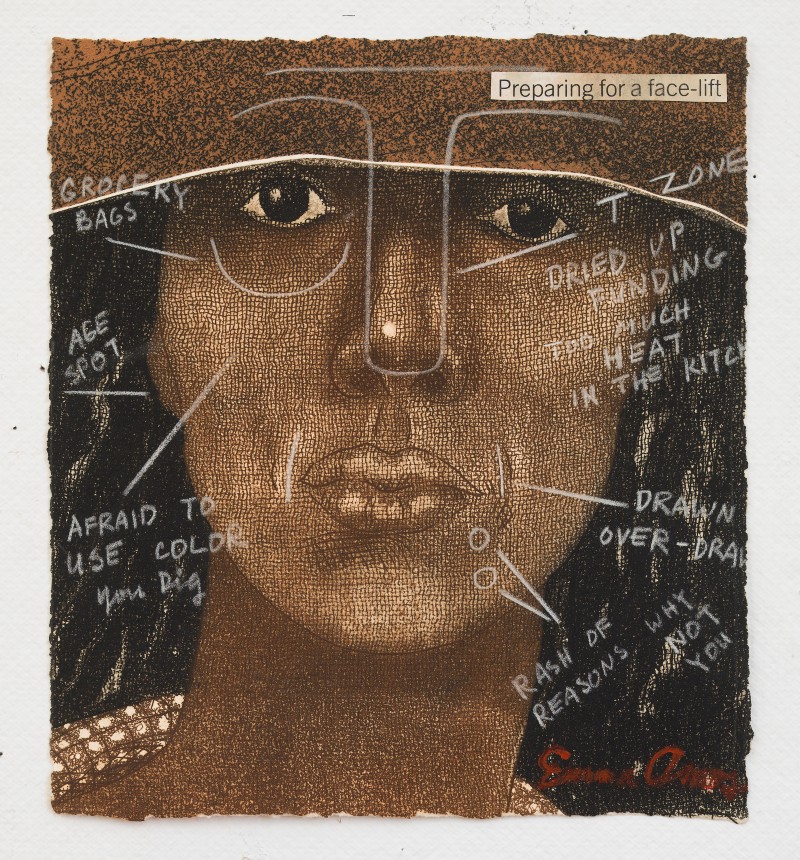

Emma Amos, Preparing for a Face Lift, 1981. Courtesy: the artist.

“Focusing on the work of black women artists, We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 examines the political, social, cultural, and aesthetic priorities of women of color during the emergence of second-wave feminism. It is the first exhibition to highlight the voices and experiences of women of color—distinct from the primarily white, middle-class mainstream feminist movement—in order to reorient conversations around race, feminism, political action, art production, and art history in this significant historical period.”

This quote of the staff of the Brooklyn Museum says it all. It is important to pay attention to an almost ignored group of black female artists that was very active at the same time that their white counterparts were on the street protesting and getting all the art world and media attention. However, I am not sure if this exhibition will reach its goal. It is a combination of documents, posters and artworks. The selection seemed random and out of balance. Why so many Horace Pippins for instance? The quality of the artworks was not that great, except Betye Saars works (91 now and still making amazing work). Especially her short video with gruesome historical images of slavery presented as a clip with exciting music. The shortcomings were caused – I think – because the exhibition was based on the obviously limited collection of the museum. A pity for a show that had to convince the viewer and set the record straight. It did not.

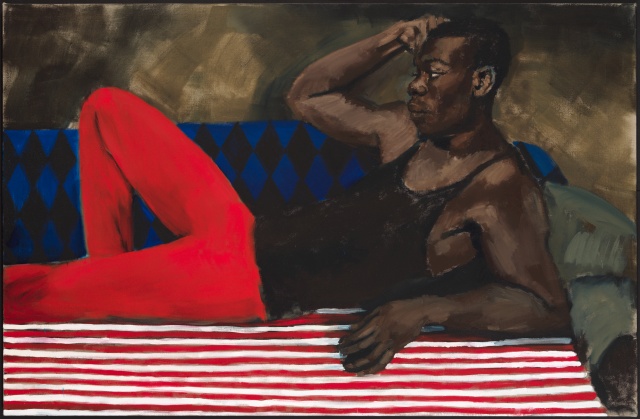

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

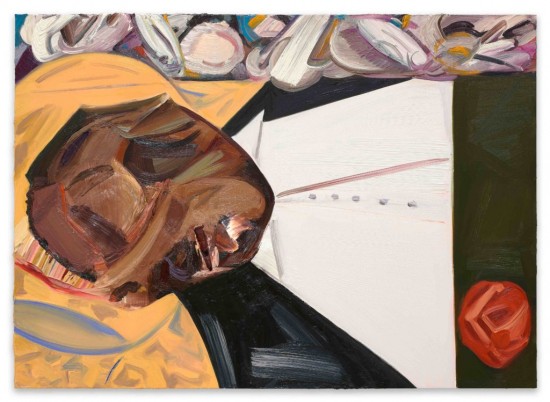

Vigil For A Horseman, 2017.

In the New Museum I saw a new series of portraits by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (1977). Large, lushly painted, dark works of mostly black men and some black women, presented in a darkened room. One would think that friends were posing for her, but the men and women are products of her fantasy. It is not so much about these people, it reflects a strategy to bring more black portraits into the overly white canon of Western art. That could explain why their environment does not have an identity. Locations and spaces are not important within a strategy like that. It also explains why her portraits seem to play with the traditional, Western codes of the genre.

Because of the way the artist paints – as if it is easy – the portraits are very lively and almost relaxed. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye is one of the most interesting painters of her generation.

1: 54 Contemporary African Art Fair Brooklyn

The 1: 54 started in 2013 in London. In 2016 it expanded to New York. This year it returned because the first presentation was successful. In spite of the deep-into-Brooklyn-location: Red Hook. 19 galleries – 12 from non-African countries – showed the work of more than 60 artists.

The space – Pioneer Works – is beautiful, but not very big. The fair feels full. Most of the works presented are of a high quality.

Armand Boua, Gnaga koi, 2017,

A few examples: The cardboard paintings of Armand Boua (1978) are interesting because of his technique – he uses a combination of tar and acrylic, he scrubs and repaints the layers – and because of their content: street kids of Abidjan, the city where he lives. Paul Onditi (1980, Kenya) also works with layers. He uses polyester inkjet plates as his canvas. He puts layer on layer, not only paint, but also for instance dots of pigment. Some parts are tactile, some are transparent. There is always a human figure overseeing an apocalyptic landscape. Stories of loneliness, of isolation?

Paul Onditi, Alien Blot, 2015.

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, Eve on an apple bottom, 2016

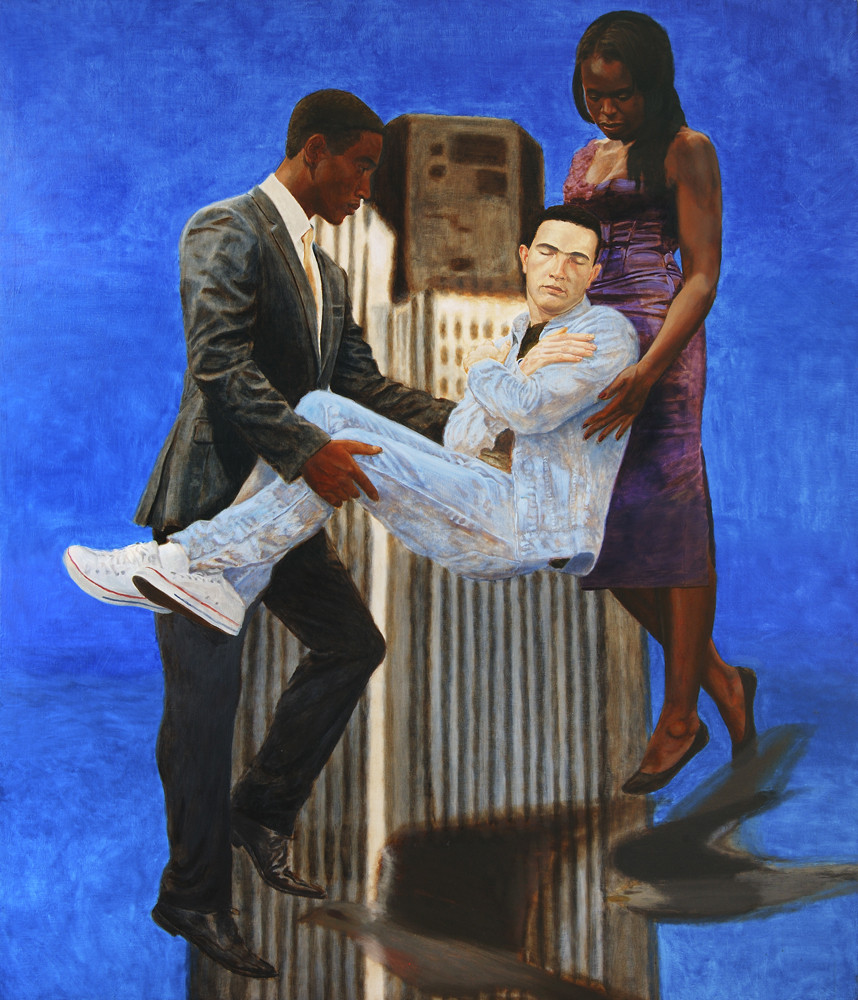

The strong, often large paintings of Kudzanai-Violet Hwami (1993, Zimbabwe) remind me of Henry Taylor’s work. Hwami’s subjects also originate from her daily life, but her life was – she lives in London now – dominated by sexual discrimination. As a lesbian she was forced to be part of a hidden subculture and, at the end, forced to live in diaspora. Kimathi Donkor’s paintings are more realistic. His narratives refer sometimes to the art history, to famed figures, but also to violence and brutality.

Kimathi Donkor, Jean Charles de Menezes Borne Aloft by Joy, Gardner and Stephen Lawrence, 2010

Aida Muluneh, Memories in Development (Part One), 2017,

Mohau Modisakeng Lefa 6, 2016

The new photo works of Aïda Muluneh are stunning. The bright colors are gone, identity and memory are now dressed in the whitest white. In contrast: Mohau Modisakeng’s self-portraits are as black as black can be. His face is squeezed by a wearing, traumatizing environment of ‘things’ (coles?).

Contemporary African art may be more and more popular now, that was not the case a number of years ago. It is impossible to prove, but fairs like the 1:54 have played a role in the acceptance and appreciation of African art. No doubt about it. It is also true that these fairs are not a fair representation of the continent. The galleries that are participating are mainly European or American, African countries without an art infrastructure or galleries (and their artists) that don’t have the money to participate are not represented. Internationally operating galleries like Stevenson, Goodman and MOMO from South-Africa or October from London are absent too, for whatever reason (against segregation?). The concept of 1: 54 is a relative success.

.

New York is the hometown of art. Also the hometown of Trump. A city that loves art and a president who does not know and does not care about art. He wants to cut art funding completely. These last weeks New York could prove that it does not care about Trump.