Horror is often cited as the genre that reflects our deepest, darkest and most base fears and this is why it is the rawest platform to explore society. The best films evoke the visceral, emotional and mental demons that reside within us and as such it is clear that race is a demon that still frightens society. The catch is that ‘society’ has meant white society and so the threat of the Other has always been present. Therefore the two-dimensional, reductive portrayals of black and minority characters have endured.

Christabel Johanson on Black Characters in Scary Movies

Still from ‘Get Out’, 2017

Oh the Horror!

Black Characters in Scary Movies

What better occasion than the month of Halloween to explore the cinematic traditions and trappings of Horror, especially when it comes to representing the black community.

It has long been an eye-rolling bad joke that the black person always gets killed. These devaluing traditions have replayed through countless sub-genres of horror, particularly slashers which echo a brutality that sits too close for comfort.

With the lack of character development, black people are the best friends, the comic relief, street thugs and sometimes even the root of the evil. This is particularly true for cultural plot devices such as a Voodoo curse, which plays on the Otherness of African and Caribbean origins. This is further proliferated through horror tropes like cannibalism and witchcraft/Satanism (see Abby, 1974) making black, aboriginal and minority spaces appear feral, dangerous and occult.

These patterns form the basis that black and minority characters are supporters rather than survivors, corrupt rather than moral and villains rather than heroes.

Bearing this history in mind, here is a look at a few Horror films with notable representations of black people and their treatment. (Warning: Spoilers ahead).

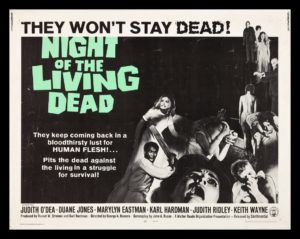

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

George A. Romero’s classic hit that arguably put zombies into mainstream consciousness featured an African-American hero. Duane Jones plays Ben but his introduction isn’t until a little later in the film. In fact there is no clue that the film would contain any non-White characters. The story begins with brother and sister duo Johnny and Barbara visiting a cemetery where they are attacked by a zombie. Johnny is taken and Barbara flees, eventually stumbling across an abandoned house. She ventures inside and is attacked again by these ‘monsters’. This is when Ben appears and saves her life.

Originally the film would have garnered a lot of controversy as its leading man was black. There would undoubtedly be an air of tension amongst white audiences when Barbara finds herself alone in the house with a black man. Yet it is Ben who secures the house and Ben who protects and comforts her as shock and trauma sink in. Throughout the film Ben remains level-headed, heroic and reasonable against the odds and is the obvious hero amongst his white counterparts who exhibit immature, selfish and cowardly traits.

As the horror of the situation unfolds Ben and Barbara discover a family in the basement; a man and wife with their ailing daughter who were attacked earlier. Then a teenage couple seeking refuge appears at the house and are taken in. As the evening draws in there is an uneasy struggle of power as the group squabble amongst themselves until a plan is hatched to refuel one of the cars. The plan goes fatally wrong resulting in an explosion, followed by a horde attacking the house. All of the survivors are killed as they fight off the zombies, including Barbara who is taken by the horde near the end of the film.

As the house is overrun, Ben barricades himself into the basement and falls asleep from exhaustion. The next morning a gang of vigilantes and sheriff’s men gather in the area, shooting the zombies in an attempt to control the outbreak. Ben calls out for help, relieved to see the rescue party but he is mistaken for the undead and shot in the head. The film ends with his body being added to a pile of corpses ready to be burnt.

The pathos of killing such a resilient hero is palpable. After my first ever viewing of the film I was shocked at the ‘twist’ ending but of course would Ben’s survival as a black hero have been too ahead of its time? Probably. It is also hard to shake the association of barking dogs and men with Southern drawls with the lynch mobs coming for black victims. Romero states that he chose Duane Jones (a former theatre actor) because he simply auditioned the best. Even if Ben wasn’t supposed to become a counter-culture icon, Romero’s judgement was rewarded by box office success accumulating $30 million in domestic and international sales as well as becoming a cult classic.

*

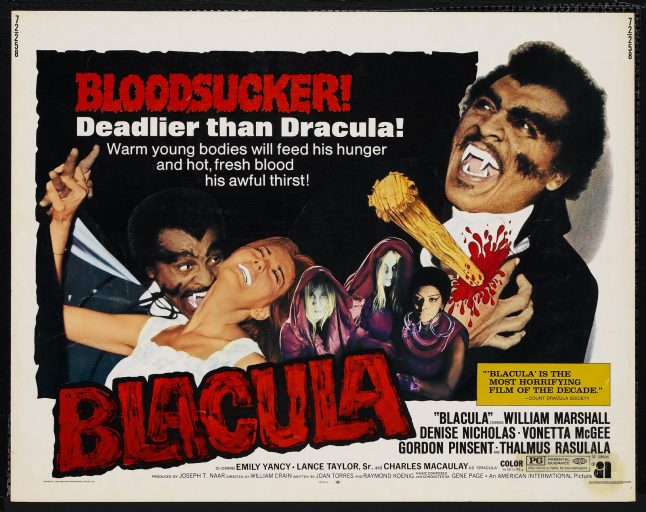

Blacula (1972)

Blaxploitation was a sub-genre emerging in the early 1970s that catered to urban audiences with plotlines involving Martial Arts (Black Fist, 1974), Action, Crime (Foxy Brown, 1974) and Horror (Blacula). The latter Blacula became a hit amongst the fleapit cinema moviegoers.

The film revolves around Mamuwalde (William Marshall) an African prince who visits the infamous Count Dracula, appealing for help in quashing the slave trade. Dracula refuses and instead turns him into a vampire, dubbing Mamuwalde as ‘Blacula’ and entombing him in a coffin. His wife Luva is also captured and dies in imprisoned by his side.

Fast forward to the early 1970s when two interior designers Bobby and Billy unsuspectingly ship the coffin over to Los Angeles. Upon opening it they release the prince and become his first victims. From then on Blacula wreaks havoc around L.A. after finding who he believes is a modern-day reincarnation of his wife Luva.

The film is now regarded as a classic of the genre, winning legions of fans through the decades. It even won the Saturn Award for Best Horror Film. So what makes it so special? Here we see a contemporary black man, a leader of his people, seek help in freeing a black community from the scourge of slavery. Dracula who has always been presented as an aristocrat is the white establishment; he is Old Money and privilege. Instead of helping Mamuwalde, Dracula regards him with contempt and curses him with vampirism.

This was topical for a society living with the recent memories of Civil Rights marches and protests, fighting resistance from the status quo that were threatened and troubled by their cause. The film also portrays a smart and powerful black leader forced into the role of villain. Blacula’s actions in America are evil but he is a monster produced by the establishment. He is named ‘Blacula’ which he does not use himself and it is an easy analogy to make; Mamuwalde was the man, Blacula is the monster and it is his ‘slave name’ which he does not identify with.

Blacula was a success through and through and spawned a sequel as well as launched the popularity of Blaxploitation around the USA and the world, even lingering in popular culture today.

*

Get Out (2017)

*

If being a black person is scary then Get Out portrays that experience with satirical success. The film begins with interracial couple Chris and Rose. Rose is played by Allison Williams of Girls fame which alone proves good casting; Williams’ character from the show Marnie personified white privilege and this heritage is carried over into the film. The couple are planning a trip to Rose’s family estate in the country to meet her parents. Chris is nervous at the prospect, especially as he is the first and only black man Rose claims she has dated.

On their way there they hit a deer and as a police officer comes over, he racially profiles Chris and Rose has to step in to intervene. This is a knowing scene, a nod to the stories of car-side police shootings flooding America recently.

At the estate Rose’s parents welcome Chris blunderingly. The atmosphere is awkward in a way that perhaps many interracial couples can understand, especially when white characters handle the situation with ‘sensitivity’. That night Chris is unwittingly hypnotised by Rose’s mother. He wakes thinking it was just a nightmare but strange occurrences appear at the family get-together; an event which Chris has not idea was planned.

The black characters at the gathering act strangely and after calling his friend Rob, a police officer back in the city, Chris takes a photo of one of the men to send. However the flash of Chris’ phone sends the man into an ‘epileptic seizure’. After this episode Chris decides to pack and leave but is stopped by Rose and her family. Unknown to him he has been auctioned off, the agenda not yet revealed. This is another racial motif; auctioning off black bodies to white bidders. The outcome is still a type of enslavement, whether physical or in this case mental.

As Chris is captured it is revealed that the family is hiding a secret; they are transferring the consciousness of older white people into the bodies of young black victims. When asking the motivation for capturing black people, the group respond that there are aspects of black people that they are happy to appropriate. This begs the questions; is appropriation connected by the same thread to slavery? It is the possession of another’s culture/identity and the coveting of their perceived privileges. Black people are here to be harvested and enslaved for the benefit of white people.

Chris is selected for this process but escapes, managing to kill everyone except Rose. As he is fleeing he meets Walter, one of the enslaved black characters and uses his flash to break the hypnotic hold. This allows Walter to shoot Rose and himself. Still alive from the wound Chris is forced to strangle Rose but cannot finish the job. Just then a police car pulls up and Rose tries to portray Chris as the attacker. However it is Rod, Chris’ friend from the city and the pair escape whilst Rose dies.

Director Jordan Peele also wrote the screenplay and the story is full of references to topical contemporary issues. From the humorous (meeting the white parents) to the serious (racial profiling), Get Out is a visitation of the milestone issues in the black experience. It was also released amidst the political backdrop of race riots and a Trump presidency. The film is so consciously a ‘black movie’ that the final escape and survival of its black protagonist is cathartic. Chris is an ‘Everyman’ character for black males trying to survive the odds.

Horror is often cited as the genre that reflects our deepest, darkest and most base fears and this is why it is the rawest platform to explore society. The best films evoke the visceral, emotional and mental demons that reside within us and as such it is clear that race is a demon that still frightens society. The catch is that ‘society’ has meant white society and so the threat of the Other has always been present. Therefore the two-dimensional, reductive portrayals of black and minority characters have endured.

Get Out is a film which bucks the trend by presenting the threat from the status quo. The figure of the black man is a more accurate reflection of our zeitgeist. The figure is dualistic; simultaneously desirable and strong but also threatening and endangered. The result is satire and political commentary grasped in the heavy-fisted delivery that only a Horror movie can deliver. So we are left with an ambivalent reaction, an uncomfortable understanding that of course something must be done but the change must come from the establishment itself. Therefore the question we must ask in these stories is not why do the black characters always die, but who is killing these black characters? I think we will find that the answer itself is art imitating life.