“If one can search beyond that particular veneer, one would find a version of Martens’ critique articulated not by the Dutch spokesman, but by the individual creators of the sculptures on view. The most rewarding result of this minimizing of Martens’ authorship is that this gesture allows the opening up a whole new view of the works themselves, which have been shown in previous exhibitions but, it seems, never confronted deeply and in their own right.”

Allison Young on the Congo project of Renzo Martens.

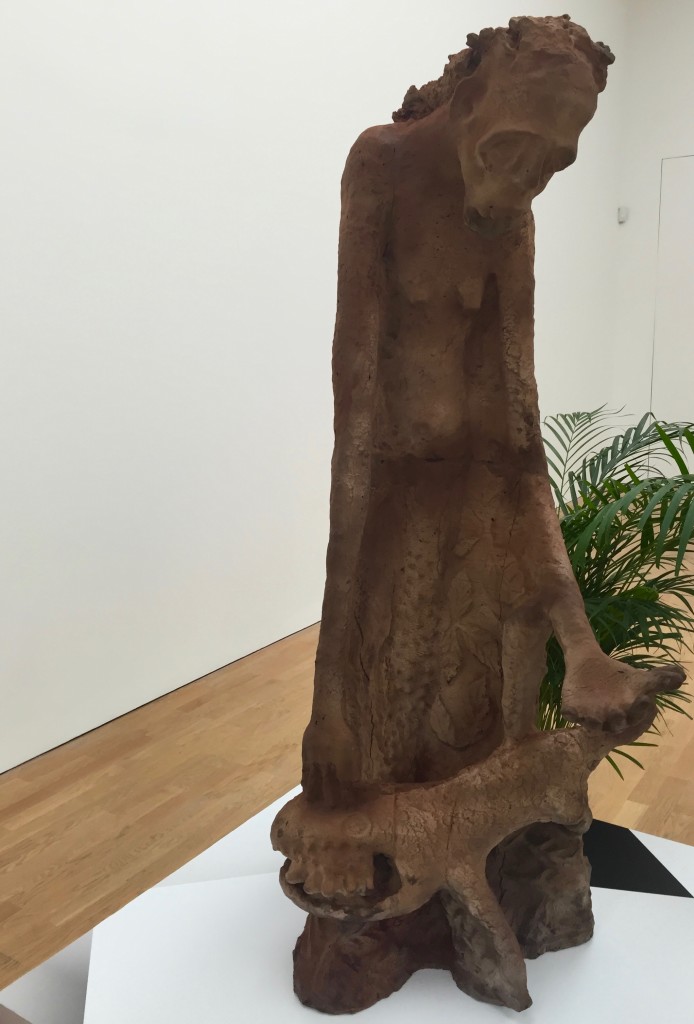

Thomas Leba, A Poisonous Miracle (detail), 2015.

A Poisonous Miracle

On Art and Labor, from the Congo River to the River Tees

I.

In a figural sculpture by Thomas Leba, originally modeled with Congolese river mud but later cast in raw chocolate, an elderly woman stands in an unsteady, hunched position, gazing down at her left arm which is being attacked by a monstrous creature. Her left shoulder hangs heavier than the right, and the expressive molding of her face can easily arrest the viewer: her mouth agape with awe, her downcast eyes enclosed by a cavernous and sunken bone structure. There is a sense of paralysis to her distress. According to a nearby label, the piece illustrates an allegorical narrative in which a grandmother “was bitten by a chameleon and subsequently possessed by evil.” The story, we learn, “emblematises the moment when an earlier generation first came into contact with money, introduced to the Congo by Belgian colonizers.” The sculpture is entitled ‘A Poisonous Miracle’.

A Poisonous Miracle, 2015.

A poisonous miracle. The phrase itself encompasses so much about the long and troubled relationship between Africa and the West, and about the consequences—both short-term and lingering—of several centuries of missionary activity, European colonization, Western involvement in de-colonial processes and the impoverishing effect of World Bank and IMF policies, all allegedly meant to help “civilize” or “modernize” the continent but, of course, to dire and irreparable effect. In the art world, this power dynamic persists in other ways: Western curators, critics and collectors since the early twentieth century have sought to discover, describe, traffic, promote and possess works of African art, all without allowing the African artist to speak on his own behalf. Only recently have we begun to engage in serious, deconstructive dialogues that force us, in this field, to acknowledge our own prejudices, to become aware of hidden agendas (both personal and institutional), and to try, sometimes failing, to be better allies and advocates without forcing ourselves into all of the speaking roles.

A recent exhibition of sculptures by members of the ‘Cercle d’Art Travailleurs de Planatation Congolaise’ (CATPC) at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (MIMA) represents a perplexing addition to this discussion. The artists are workers on a palm oil plantation, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which was originally owned and run by Unilever, a British-Dutch corporation founded in the early twentieth century by Lord Leverhulme. The workers have begun to make art in recent years under the auspices of the ‘Institute for Human Activities’ (IHA), an organization founded by Dutch artist Renzo Martens, who himself has been criticized for his ambitions to “gentrify the jungle” through the establishment of rural art workshops.

Emery Muhamba working on self portrait.

Before discussing the exhibition at MIMA, a bit of backstory may be in order. Martens’ aims are, somewhat naively, humanitarian: proceeds from sales of artworks return to the artists, and the facilitation of creative self-expression is seen as a step towards cultural regeneration. Much ink is spilled on the European theft of Congolese artworks during colonialism, as well as the subsequent role such artifacts played in fueling the development of modernist art in Europe. The initiative is premised on the inherent value in a community’s ability to claim and create its own visual history and culture. (This doesn’t seem entirely thought-through, however, since the artworks are subsequently sold in Western markets, just like their predecessors in the nineteenth century.)

One sympathetic commentator on Martens’ recent exhibition in Berlin explains that the workers are now “able to speak for themselves through art, to take control of their identities, and the way they are perceived without the exploitative presence of a middleman.”(1) I believe wholeheartedly in the importance of self-expression, and the artists have asserted that their experience has been positive. But, of course, there is a middleman, and he has not been invisible. It seems difficult to comprehend that a Dutch artist based in Brussels would not understand his mere presence in rural Central Africa to be fraught with historical baggage—Holland’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade predates colonialism by several centuries, and Belgium’s own brand of imperialism in the former Belgian Congo was one of the most violent in history.

Installation view, 2016.

As such, some critics have questioned the artist’s own positionality as a white, European male; his attempt to improve the lives of disenfranchised workers in Africa as part of a project for which he has ultimately been given credit (and career gain) has especially been subject to scrutiny. Even a seemingly “benevolent” Western presence, in this context, ultimately repeats the power dynamics established by colonialism. The artist’s self-assigned role as a kind of savior is troubling in this regard, and his unblinking employment of the term “gentrification” sits poorly even with viewers in cities like London and New York, where the appearance of an art gallery or a coffee shop in a low-income neighborhood often foreshadows the raising of luxury apartments and the displacement of long-time residents. It is difficult to tell if Martens is serious when he says things like, “I’m basically putting a white cube in the forest to see what it does.”(2)

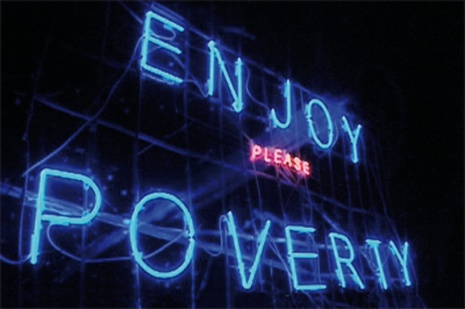

There is also the question of Martens’ identity as an artist, rather than the director of an aid organization or NGO. As an artist, he sometimes obscures his motives in the language of performative critique, blurring the boundary between art and life, satire and reality. One of his most provocative ventures was the mounting of a bright-blue fluorescent text in the Congolese rainforest—à la Bruce Nauman, Glenn Ligon or Tracey Emin—that read ‘ENJOY POVERTY’. It was meant to suggest that Central Africa’s main “exports” are images of war or disease, which increase Western sympathy but ultimately generate no returns for the people in question. The catchphrase was directed towards the Congolese community in which his installation was embedded. While the imbalanced representation of Africa in the media is an important topic, I can think of projects that deal with it in more palatable ways, such as Everyday Africa, a collective of photojournalists who work to challenge stereotyped images of war and starvation by uploading digital images of “everyday” life, in all its diversity.

Renzo Martens, Enjoy Poverty, 2010.

As Berlin’s KOW gallery admitted in 2015, “no artistic critique of living and working conditions in the Congo changes those conditions.”(3) Joe Penney also wrote in 2010 that Martens “has gone to the country to lift them out of poverty, made a film that he will earn his living from, and given nothing but a meal in return.”(4) Martens does so self-consciously, but is it ethical to keep such critical distance when in such close proximity to one’s subject?

Installation view, KOW Gallery, Berlin, 2015.

In light of the very polarizing reception to-date of Martens’ practice, the present exhibition marks a significant shift in the presentation of his work, and has the potential to improve the discourse around the project at large. The curatorial staff at MIMA are well aware of the controversies surrounding Martens and the IHA, and rather than shying away, they lean in and embrace a strategy of full transparency.

Most importantly, it is the excision of the artist’s own name and his claim to authorship that makes this iteration so unique. For the first time, the promotional material states that this is an exhibition of sculptures by Congolese artists, full stop. Also for the first time, the names of artists like Thomas Leba are recognized in the galleries, and the artists’ voices are heard: each wall label offers a short biographical paragraph and a transcription (in English, from Kikongo, via French) of the artist’s thoughts about his or her sculpture or about the process of making art, in general. Michael Kasiama, for instance, states, “I spent a lot of time with deep thoughts. Now, art enables me to express them. I hope this project will continue, because man is what the head is.”

Installation view, 2016.

The choice to remove Martens’ name from the promotional material (save for some fine-print facts about the IHA) originated with curator Miguel Amado and director Alistair Hudson, who worked closely with the artist to change the tenor of his work. They were interested in the questions that Martens raised about the role of art in transitional societies, but they encouraged him to reflect more deeply on the politics of his own centrality in presentations of his work. Most crucially, I think, they also considered how themes of economic globalization and disenfranchisement might speak to the experiences of their own local audiences. In order to understand some of the nuances of this exhibition, one actually needs to know a little more about MIMA.

II.

I arrived in Middlesbrough, a post-industrial city in North Yorkshire, England, on an overcast and blustery “spring” day. Despite the lackluster weather, the atmosphere at MIMA was lively, buzzing with activity. Just outside the building, the grassy area adjacent to the entrance was being dug up, seeds deposited into its soil, as part of an initiative to convert the space into a community garden that will produce vegetables, flowers and food for shared meals in the museum. The garden is being tended by museum staff as well as volunteers from Middlesbrough, many of them refugees from Africa and the Middle East who have settled here in recent months. The city, in fact, is the only locality in the United Kingdom that has actually exceeded the set “population ratio” enforced by the government as a guideline for placing new asylum seekers.

MIMA is a regional art museum situated amidst the seaside “steel towns,” as far as conceivable from Britain’s art capital of London. Last October, greater Middlesbrough was devastated by the closure of Teesside Steelworks, a conglomeration of blast furnaces and coke ovens that have fuelled the job market here for about a century—that is, until the industry turned to China.

MIMA, Middlesborough.

In the context of a city struggling to rebuild, MIMA aspires not to mount expensive, blockbuster exhibitions, but instead to be a “useful” museum, to demonstrate that art can work in society to facilitate social change or revitalize communities. If one distills the raison d’être of Martens’ IHA to its most basic form, it echoes MIMA’s own hypothesis that making and interacting with art can improve one’s quality of life and effect community-wide social change.

Recently, Middlesbrough’s newer residents seem to have helped jumpstart the local economy. The promenade nearest the museum is brimming with Turkish restaurants and small business owned by African and Asian immigrants. When I met with Hudson, he acknowledged the many ways in which this small, predominantly white, working-class English town has itself been so tangibly impacted by political and economic events in East Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

As such, one of the merits of the exhibition at MIMA is that it establishes a dialogue about globalization and the invisible networks that link disparate parts of the world, from the DRC to Middlesbrough.

The production process of the CATPC sculptures speaks to such international labor networks: the works are created in Congo River mud, hand-layered over metal armatures, and then 3D-scanned on-site using iPads. This data is then sent to the Netherlands, where lost-wax molds are 3D-printed, allowing the sculptures to be re-cast in raw chocolate. In both concept and materiality, the project reflects themes surrounding capital, circulation and consumerism.

Integral to the display is an acknowledgement of all forms of labor involved in the creation of the exhibition—artistic, intellectual and menial. In place of the white plinths on which the CATPC’s sculptures are typically mounted, MIMA has commissioned Metahaven, an Amsterdam-based design studio, to print motifs that decorate the pedestals, which now bear the graphic logos of the IHA, the CATPC itself, and the exhibition’s primary sponsor, Barry Callebaut, a multinational cocoa manufacturing giant. A full list of corporate partners is listed on a vinyl text at back, alongside production credits for everything from “plinth motif conceptualisation” and “chocolate casting” to shipping and insurance.

In the United Kingdom, at the moment, museum sponsorship is a hot topic: in early March, it was announced that the Tate would finally cut its long-standing and controversial ties with the oil giant BP after a succession of headline-making campaigns and protests. Tate Modern is still, however, partnered with Unilever in its sponsorship of an annual commission in the Turbine Hall, and this fact is not lost on MIMA. The exhibition guide explains that the members of the CATPC “lack the resources to break free from a purely extractive economy, yet they have been contributing to the funding of phenomena such as the Unilever Series at Tate Modern,” which has supported projects by artists like Olafur Eliasson, Anish Kapoor and Tino Seghal.

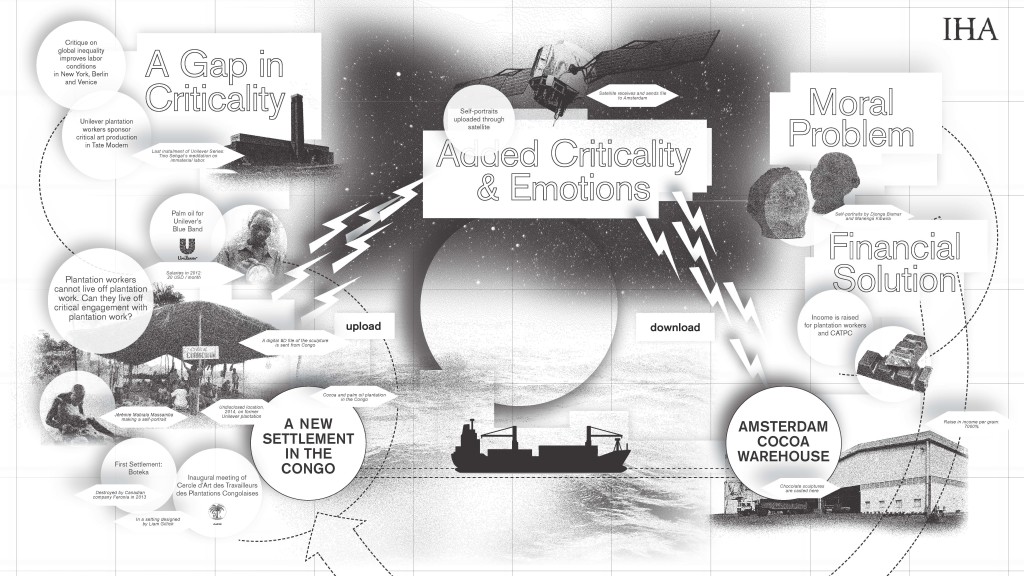

Infographic.

To the left of the entrance, an infographic flow-chart visualizes the complex network in which the project is enmeshed: viewers can note the entanglements that link the art market, the palm oil plantation, the CATPC, the cocoa manufacturer in the Netherlands, alongside many other nodes of production and consumption (or, in the graphic’s terms, “uploading” and “downloading”) between Holland, the United Kingdom and the DRC. The chart excludes the municipal context, but could easily be expanded to encompass the globalization of the steel industry and its impact on labor in Middlesbrough. The corporate aesthetic of the vinyl texts, logos and infographic—echoed, as well, by the interspersing of Ikea house plants throughout the gallery—seems to contrast the organic, hand-made aesthetic of the sculptures, but ultimately we re reminded that these, too, were mechanically reproduced in a transnational context.

One bubble on the left-hand side of the infographic proposes the following: “Plantation workers cannot live off plantation work. Can they live off critical engagement with plantation work?” It is important to note, despite all censure, that the workers are paid for their artistic labor and receive proceeds from sales, and that this supplemental income makes a significant difference in their quality of life. Of course, the plantation itself is not pressured to reform, so ultimately, our complicity in the structural maintenance of poverty needs to be addressed.

Amado and Hudson know that transparency alone cannot erase the controversial terms of Martens’ presence in Africa, but they are interested nonetheless in starting an open conversation about art and patronage, and about how economic networks bind life in London, Amsterdam or Middlesbrough to the Congolese rainforest.

Installation view, KOW Gallery, Berlin, 2015.

III.

In 2014, Jerry Saltz characterized Oscar Murillo’s exhibition, ‘A Mercantile Novel’ at David Zwirner Gallery in New York, which re-staged a Colombian chocolate factory in a white cube in Chelsea, as “a nightmare of self-congratulatory hubris” and “pretend activism at its most deluded.”(5) What seemed unsettling to the critic about A Mercantile Novel was not necessarily the artist’s exposition of factory labor in his hometown of La Paila, Colombia, but the performance of this topic for the 1%, in a Western financial capital. The question must be asked whether an artistic critique of inequity that is staged before an audience of financial elites (or by a Western-outsider artist) can ever do more than repeat the transformation of poverty into a spectacle, or serve as a conscience-clearing exercise for the privileged-but-socially-aware among us.

The exhibition at MIMA, in this sense, does benefit from its location in Middlesbrough (as opposed to London) and from its integration with MIMA’s investment in art as a tool for social change. The city is home to a large community of Congolese immigrants, who were invited to participate in arts programming and family workshops in conjunction with the show. But I can’t help but wonder whether this kind of engagement would be better suited to less controversial projects: Kim Berman’s Artist Proof Studio in Johannesburg, South Africa, for instance, comes to mind as an example of a community-run printmaking workshop founded on democratic ideals of collaboration, reconciliation and healing through art. Some of the language in APS’s mission is consistent with Martens’ promotional materials—APS hopes, for instance, that its members may “reach self-actualisation and make a difference in society” through printmaking—but the initiative, refreshingly, lacks the veneer of market-savvy postmodernism projected by the IHA.(6)

If one can search beyond that particular veneer, one would find a version of Martens’ critique articulated not by the Dutch spokesman, but by the individual creators of the sculptures on view. The most rewarding result of this minimizing of Martens’ authorship is that this gesture allows the opening up a whole new view of the works themselves, which have been shown in previous exhibitions but, it seems, never confronted deeply and in their own right.

Mbuku Kimpale, Selfportrait without Clothes, 2015.

The sculptures are moving and unexpectedly modern, and reflect a diverse range of experiences and concerns. One of the only female sculptors, for instance, Mbuku Kimpala’s ‘Self-portrait without Clothes’ depicts a naked woman sitting upright atop the pedestal; her feet are planted in front of her and her knees are raised and opened, revealing the parted lips of her vagina. Her right arm is bent and rests on her knee, her hand whimsically bent at the wrist as if she were laughing in conversation amongst friends. Kimpala writes, “A woman must always be proud of her body, even if she owns only one single dress.” In just one short sentence, she manages to preach a universal gospel that all women can understand, but also to remind those of us who own more than one dress of our Western privilege and the reality of global inequality.

Many sculptures attest that the artists are well-aware of the ways in which their condition of subjugation is a lasting result of colonialism. Cédric Tamasala’s ‘How My Grandfather Survived’ illustrates the story of a Belgian missionary who “rescued” the artist’s grandfather from poverty, but in so doing, alienated him from his own community. A poisonous miracle, indeed.

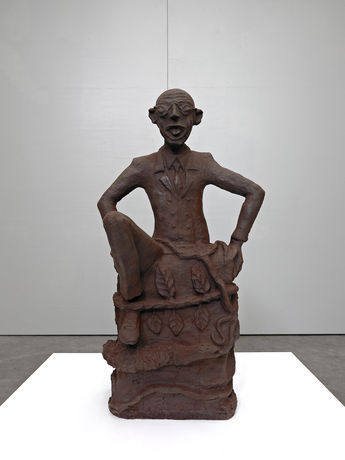

Jérémie Mabiala/Djonga Bismar, The Art Collector, 2015.

The Art Collector in Congo.

One of my favorites is the sculpture that immediately faces the viewer at the entrance to the gallery. Made by Jérémie Mabiala and Djonga Bismar, it is entitled ‘The Art Collector’ and depicts a bald man in glasses and a suit. His posture is confident and he rests his hands firmly on his hips as he faces forward, in confrontation. Mabiala and Bismar write that this character must decide whether to covet or distribute his wealth. It is as if these artists, in the depths of the Congolese rainforest, have held a mirror up to Martens himself, and to all of the European viewers who they will never meet in person. This is by far the most potent form of critique that the exhibition performs.

(1) Nora Kovacs, “Review // Discussing the Matter of Critique with Renzo Martens at KW Institute for Contemporary Art,” Berlin Art Link, May 26, 2015, http://www.berlinartlink.com/2015/05/26/review-discussing-the-matter-of-critique-with-renzo-martens-at-kw-institute-for-contemporary-art/

(2) As quoted in Stuart Jeffries, “Renzo Martens – the artist who wants to gentrify the jungle,” The Guardian, December 16, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/dec/16/renzo-martens-gentrify-the-jungle-congo-chocolate-art

(3) http://www.kow-berlin.info/exhibitions/renzo_martens__institute_for_human_activities

(4) Joe Penney, “Enjoy Poverty: Interview with Renzo Martens,” Africa is a Country, July 2007, http://africasacountry.com/2010/07/poverty-for-sale/

(5) Jerry Saltz, “Seeing Out Loud: Why Oscar Murillo’s Candy-Factory Installation Left a Bad Taste in My Mouth,” Vulture, May 7, 2014, http://www.vulture.com/2014/05/saltz-on-oscar-murillos-candy-art.html

(6) See Mission statement on the website for Artist Proof Studio, http://www.artistproofstudio.co.za/about-aps

Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise ran at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art from 6 February – 29 May, 2016.