“In spite of the gaps, the missing opportunity’s and the uneven quality of a number of works on display. ‘Represent’ is an exhibition that is worth visiting. For visitors who are not familiar with art of black American artists it makes a good introduction , for specialists, the exhibition leads to a wider discourse on African American art.”

Rob Perrée reviews ‘Represent: 200 years of African American Art’ in Philadelphia Museum of Art.

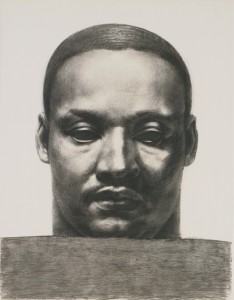

John Woodrow Wilson, Martin Luther King, 1981.

Represent: 200 years of African American art

MORE OR LESS

A couple of years ago I had an interview with the Dutch novelist, poet and art critic K. Schippers. At the time he had just published the book ‘The Bride of Marcel Duchamp’, a personal search for the artist, in particular for his famous work ‘The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even’ (1915-1923). As part of his research Schippers made a trip to New York and had located one of the studios of Duchamp. By accident . From there he travelled to Philadelphia to visit the Philadelphia Museum of Art to see ‘The Large Glass’, which is how ‘The Bride Stripped Naked….’ is nicknamed. A valuable moment. “The large glass. Finally I can see it. I have waited for this moment for years. (…) It is much bigger than I had in mind, two glass plates, one above the other, divided by a silver-colored horizon. About three meters high and two meters wide.” He describes it as “A love story, an erotic fairytale”. His fascinating book and the enthusiasm of the writer enticed me to go back to the museum to view the amazing Duchamp collection again.

Moses Williams, Charles Wilson Peale, 1800?

Moses Williams, Charles Wilson Peale, 1800?

What I did not know at the time was that the Philadelphia Museum of Art owns a large collection of African American art, covering a period of more than two hundred years. It is more than 750 pieces. In the past I had seen individual works spread over the rooms of the museum, but I did not realize that most of the 750 works were stored in the vaults of the museum. Several years ago the staff decided that the collection needed a book to make the works more accessible to the public and to give specialists the opportunity to discuss the policies that shaped the collection. Through the course of working on the book they came to the conclusion that it would be a good idea to combine the publication with an exhibition of a representative selection of the collection. The thought was that it would make a strong statement to the public at large, and especially to the sizable African- American community in the area as well as drawing attention to the book.

The book – ‘Represent: 200 years of African American Art in the Philadelphia Museum of art’- is now available and in January the exhibition – ‘Represent: 200 years of African American Art’ – opened. The book gives more than the title promises, the exhibition gives less.

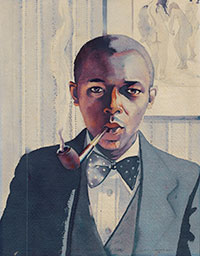

Samuel Joseph Brown, Smoking my Pie, 1934

Samuel Joseph Brown, Smoking my Pie, 1934

The exhibition is presented near the west entrance of the giant building on the ground floor. The room is opposite of the museum store. Piles of the new book wink at the guileless visitor. Strategically planned? Could be. The exhibition room is as big as the shop. Big for a shop, limited for an exhibition with ambition. The consequence is that only 10% of the collection is on display. If the perforce strict selection has increased the quality is open for discussion. Therefore you need to know the full collection.

The works are grouped by period. Themes characterize the five periods on the timeline: Early America, Imagining Modernity, Abstract Approaches, Past Made Present and Facing the Collection. It helps to put the works in perspective, but it also creates a somewhat dutiful, almost educational exhibition. Surprises caused by unexpected combinations fail to happen. The last part is an exception on the rule. A collection of portraits from different artists, in different styles and from different times fills the walls. An exciting palette of artistic possibilities and means. From a mysterious photographic triptych of Dawoud Bay to a life-size photorealistic painting of Barkley L. Hendricks, to a vibrant, expressionistic portrait of James Baldwin by Beauford Delaney to a painterly photo-self-portrait by Donald Camp.From a ‘clumsy’ but touching little painting of Bill Traylor to a classic woodcut of a preoccupied Countee Cullen by Aaron Douglas. A presentation that moves and intrigues me more than the rest of the exhibition. It is the most original and clearest collage of 200 years of African American art.

Glenn Ligon, Untitled, 1992.

Glenn Ligon, Untitled, 1992.

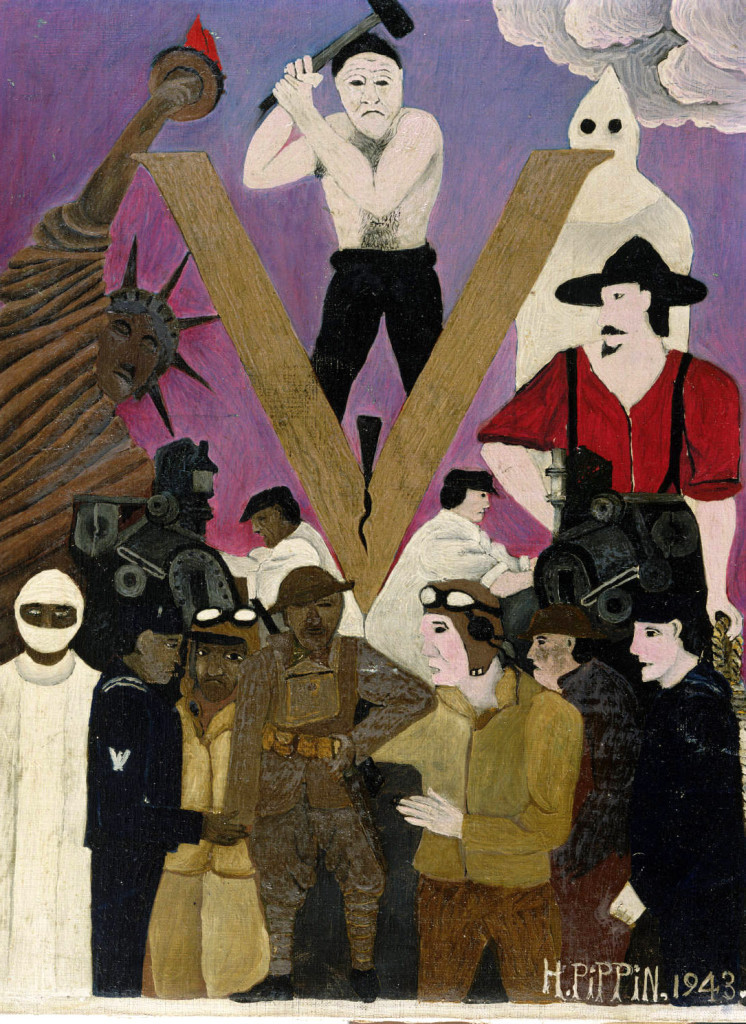

For visitors who are not familiar with African American art, ‘Represent’ gives an interesting and valuable introduction. More informed visitors will enjoy the pleasure of the reunion with known works, of the coming-to-life of works they only know from pictures, of the relations between works or between artists they never thought off before. The silhouettes of Moses Williams (1775-1825), enslaved by the family of Philadelphia artist Charles Willson Peale, lead to the silhouettes of Kara Walker; the beautiful painting ‘Annunciation’ of Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937) shows that the artist who moved to Paris was influenced by the Western art tradition; ‘The End of the War: Starting Home’ (1930) of Horace Pippin (1888-1946) is a good example of the commitment of many African American artists, regardless of the time in which they were active; the beautiful ‘Old Mole’ of Martin Puryear (1941) blurs the presumed divide between art and craft and shows his interest “in a broad conceived cross- cultural heritage of preindustrial and tribal arts”; the exhibition as a whole illustrates how figurative African American art in general was and still is. The wall painting of Odili Donald Odita (1966) not only attracts attention because of the bright colors, but also because of the exceptional, abstract and conceptual nature of it.

Alma Thomas, Hydrangeas Spring Song, 1976.

Alma Thomas, Hydrangeas Spring Song, 1976.

The title of the exhibition suggests that it is a representative survey of 200 years of African American art. That is debatable . The content of a museum collection depends on the policy of the staff, the time period in which the collection is put together, the available financial means, the influence and power of advisory committees etc. It is seldom representative. This exhibition is the product of a system in which all of these forces have acted. The first 100 years are represented with a relatively small amount of works. Also in the contemporary part of the exhibition I didn’t see important, iconic artists like David Hammons, Kerry James Marshall, Adrian Piper, Fred Wilson, Gary Simmons, Lyle Ashton Harris, Kehinde Wiley and Leonardo Drew, to mention a few. I know that the art market makes it very difficult for many museums to keep their collection up to date, but why not be more modest in presenting surveys if you are an innocent victim of that problem? Strangely enough, the book that was the main motive to organize the exhibition is more modest. It has a longer and therefore a more limited title than the show – ‘200 years of African American art IN THE PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART’ – while the texts in the book, especially the extensive introduction of Richard J. Powell, succeed in covering a much wider field.

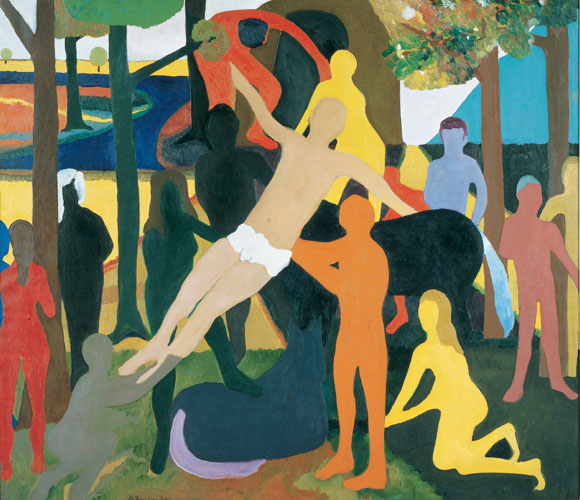

Bob Thompson, The Deposition, 1961.

Bob Thompson, The Deposition, 1961.

The status of a museum depends not so much on the size of its collection but on the quality of it. The Marcel Duchamp collection raised the status of the Philadelphia Museum of art, no question. I have my doubts about the role of the African American art collection. It is absolutely a plus that the museum collects African American art for such a long period of time. Many American museums were late and safe starters to this process . They only showed their interest in the 1990’s when it became impossible to ignore the artistic success of artists like Hammons, Walker, Ligon, Wilson and Drew. But, if the acquisitions of the Philadelphia Museum were the best selection of pieces to get……??? I am not convinced. Jacob Lawrence made better works; the photos of Roy DeCarava, James Vanderzee and Gordon Parks don’t show the unique quality of their makers; of Sam Gilliam, Kara Walker and Alison Saar for instance there are only prints and etches, the real works are missing; where are the installations or videos of the collected artists?

Horace Pippin, Mr. Prejudice, 1943.

Horace Pippin, Mr. Prejudice, 1943.

In spite of the gaps, the missing opportunity’s and the uneven quality of a number of works on display. ‘Represent’ is an exhibition that is worth visiting. For visitors who are not familiar with art of black American artists it makes a good introduction , for specialists, the exhibition leads to a wider discourse on African American art.

The very informative book is a must have. It fills the gaps of the exhibition. The exhibition is not so much supporting the book, the book is necessary for the full understanding of the exhibition.

Kara Walker, No World, 2006.

Kara Walker, No World, 2006.

The exhibition is still on till April 5, 2015 in Philadelphia Museum of Art.