Petersen is a multi-disciplinary artist whose discourses focus on photographic ‘self-portraits’, installations and multi-sensory based performance. Her work has been a journey through her Muslim, Cape Malay, South African, and Indonesian past, with the hope of constructing a better future by taking back what has been robbed from her culture – heritage, history, pride, self-worth and dignity.

Candice Allison on Thania Petersen.

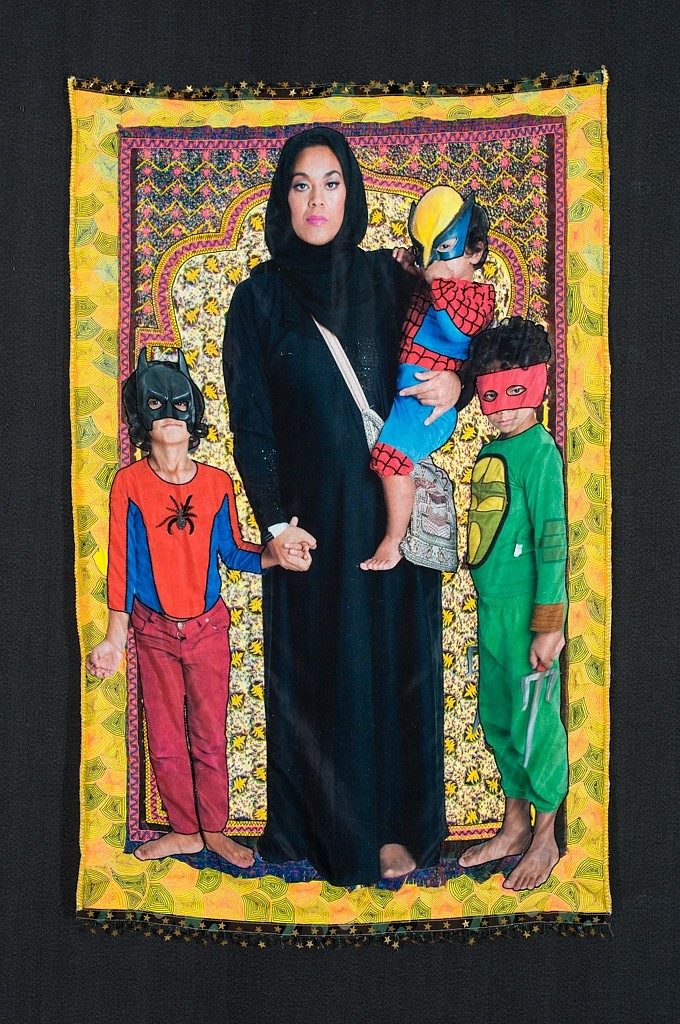

Remnants, 2016.

Thania Petersen

Our religion is being so misrepresented in the media now, and we are always being spoken of as being so oppressive and sexist towards women, and I just refuse to believe that.

I have arranged to meet Thania Petersen at 8.30am on a Monday morning. Between us we had made and broken several promises to meet (because of the Cape Town Art Fair). She has three young boys, so I had, unfairly, expected her to be late. She arrives right on time, whirling in on a breeze of color, wearing a bright lipsticked smile. Thania is cheerful, authentically charming, and flamboyant. Like the extravagant entrance to her exhibition Remnants (2017) at Everard Read Gallery in Cape Town – an installation of thousands of flowers covering the front facade of the gallery – no announcements are necessary. Thania has arrived.

Born in 1980 in Cape Town, Petersen’s father was a political exile and she lived in the UK for nearly twelve years. She studied at Central Saint Martin’s College of Art in London from 2001-2003, then trained in both Zimbabwe (2004) and a year later in South Korea (with renowned Korean ceramist Hwang Yea Sook). She subsequently participated in the South Korean Ceramic Biennale that same year. From 2000-2007 Petersen remained the resident painter of props and costumes for the London based Yaa Asantewa Arts Group at the Notting Hill Gate Carnival, before settling back in Cape Town full time. In 2015 Thania has been featured with Brundyn+ at the Cape Town Art Fair and with the AVA at Johannesburg Art Fair. I Am Royal marked her first solo exhibition at the AVA Gallery in August 2017. This year I saw her partake in various exhibitions including Studio at the South African National Gallery and her first solo presentation at Everard Read, Cape Town.

Petersen is a multi-disciplinary artist whose discourses focus on photographic ‘self-portraits’, installations and multi-sensory based performance. Her work has been a journey through her Muslim, Cape Malay, South African, and Indonesian past, with the hope of constructing a better future by taking back what has been robbed from her culture – heritage, history, pride, self-worth and dignity. To create visibility for the invisible, the ‘other’ on a continent which fails to notice its children. The Nameless people who are neither white nor black. A nation born on the soil of Africa but never accepted – ‘the bastards’, the ‘other coloreds’, the ‘mixed breed’, amongst many other derogatory classifications which in the new South Africa are considered politically incorrect, leaving an entire cultural/racial group effectively nameless. A direct descendant of Tuan Guru (an Indonesian Prince in the late 1700’s brought to South Africa by the Dutch as a political exile), she explores the universal themes of personal and historical identities by reconstructing herself in varies guises often invoking ‘what remain from our ancestors rituals and history in our lives today’. From an intensely personal perspective as an Indonesian ‘Malay’ woman and mother, Petersen adopts a breadth and diversity of theatrical personas – a mythological Queen, a botanical Goddess, to various personal reflections of her childhood growing up as a girl in a secular Muslim society. Her reference points include the history of African colonial imperialism, contemporary westernized consumer culture, and the legend and myths of Sufi Islamic religious ceremonies.

She drinks black tea sweetened with honey while we talk about memory and ritual in her work. The importance of redressing history and reclaiming heritage. Reclaiming pride in her religion as a Muslim woman. Her anger at the injustices, the hurt and pain caused by colonialism. Her struggle for self-worth, and helping her children find self-worth, as part of a historically and almost perpetually displaced community. What I keep drawing from the conversation is that she is searching for an acceptance, for herself, her children and for her community, within the broken shards of South Africa’s multi-cultural promises.

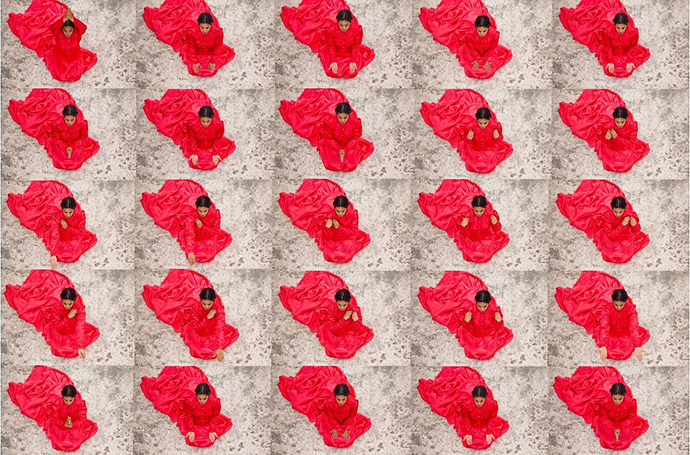

Avarana, 2016.

CA: You have just closed you first major solo show, Remnants (2017), at Everard Read. Can you tell me briefly what the show was about?

TP: There were three different parts to the show, and they all combined in the end, but they dealed with different aspects of whatever conflicts me. The room upstairs, which I said was my inner conflict and downstairs was my outer conflict. Upstairs there were two bodies of work, the one being Remnants (2016), and the other one called Avarana (2016). Avarana is about an issue that I needed to deal with last year which made me contemplate the role concerning women in society today. I used the hijab as a metaphor to address certain issues. Visually, the hijab is very prominent in the works, but the work is not about the hijab, it’s purely just a metaphor for something that is meant to protect women, but even what is meant to protect women is often used to oppress women, you know, to betray women, like our safest spaces. It came to me after I got news that someone very close to me had been abused as a child, in a place that was supposed to be safe. I tried to speak of this by using a global narrative where women are flocking to the West because they think it is a place of liberation, and now they (Muslim women) are being forced to take their clothes off, while in the East they are forced to put their clothes on. Something even as superficial as your clothing is dictated to you still, which just addresses something so much larger, so much deeper, than just clothing, because where is our voice actually still heard in society? It’s not even about just Muslim women, it’s about all women. I think the world is becoming more and more right wing, and in a sense, we are more under threat than men are in this sort of right wing movement.

I try and address all of these things, but I also try to address our role in a spiritual sense, and so in the film I walk through the Castle of Good Hope, around an empty fountain, because the Castle is, for me, I think it is an incredibly masculine space, and it is also a space that symbolizes an oppression that we all understand, whether you are male or female, black or white, or orange, or yellow; and so I navigate my body through this space the way we navigate our bodies through society. The way I walk around this particular fountain, is reminiscent of the way we do our pilgrimage, the way we walk at our Ka’ba, and what I try to address by doing that is to show that when we do this particular movement around the Ka’ba, we actually pay homage to a woman, her name is Hajar, and the only reason we pay homage to her is purely for being a woman and for being a mother, not for being a conqueror or a world leader.

Avarana, 2016.

CA: She was just a normal everyday woman and there was nothing uniquely special about her?

TP: Yah, but that’s just it, maybe being a mother and being a woman is special. Our religion is being so misrepresented in the media now, and we are always being spoken of as being so oppressive and sexist towards women, and I just refuse to believe that. So I questioned whether or not it is truly that way if in our sacred rituals it speaks of something else. Maybe there is a misinterpretation that has happened somewhere deeper than the media, long ago.

.

CA: Within your religion as well, or do you think it is something applied from outside?

TP: I think it’s everywhere, you know, not just from the media, but from academics and scholars. There are so many ways of interpreting things, and things maybe get interpreted for something other than the benefit of the religion. I think we all feel that in society, all the time, not just with religion but also things like struggle or political movements, things just get a little bit tangled – what did Trump say recently, which is a different kind of a truth..?

Remnants, 2013.

CA: Oh, you mean alternative facts?

TP: Yes, it’s like alternative facts. And so somethings just get left out conveniently as, well you know alternative facts.

.

CA: The facts are changed to suit a particular narrative.

TP: Exactly, and I think it is something that has existed for a long time. So I just tried to address these things, particularly in this body of work, with reference to us as women. Even though I did say I’m not into gender politics, here we go.. (laughs).

Remnants, 2016.

CA: You don’t wear a hijab.

TP: No, I don’t.

CA: Is that your choice or is it just not required of you in your particular religious sect?

TP: It’s just my choice. I don’t have a problem with the hijab. I don’t think there is anything wrong with it. I think there is something wrong with judgement, and I feel that I am ok. I feel it’s what is inside that is important. Maybe one day I will put on a scarf when I feel I need to. Or maybe one day I won’t.

.

CA: How did you identify with it in your work then?

TP: Because I understand what it is for, and I don’t think there is anything wrong with it. I know women who wear it and I know why they wear it. I find it beautiful and it is something I can relate to, maybe it is something I will end up doing, but it is not something I feel like doing right now, you know, we are all at different stages in our life and I think we all practice spirituality in a different way. That is what needs to be respected more than anything else. It’s that idea again that takes you back to judgement. Maybe that woman isn’t any more religious than I am, you know, I think we just need to do different things for our soul sometimes. Some people need to do it physically, and other people maybe need to do it in a more abstract manner. Maybe I do it through my art. But we all find ways to practice what our soul needs.

Botanica l imperialism, 2017.

CA: You have talked about the two spaces in your exhibition, the inner and outer conflict. I think that was very effectively conveyed, it actually almost felt a bit jarring, like it was two completely different shows. Do you think those two conflicts, do they exist together in harmony, or do they exist in conflict for you as well?

TP: Conflict, definitely, but I am starting to find harmony within it. It’s always been a conflicting space for me, because I have always felt torn between the two. I think that’s why the work downstairs is so important, because we all have desires, right? And because we grow up in a certain way, where we are brought up to believe certain things, and we think certain things are right and certain things are wrong, and you can’t help the desire to sometimes want what’s wrong. It’s like being on a diet. Every morning you wake and say ‘I’m not going to eat cake’, and then you say, ‘oh I’ll just have a little piece’, and you know the consequence is that you’re going to pick up weight but you don’t mind, it’s just a little bit. I think it’s about trying to understand yourself, it’s about growth, and then in the end you realize maybe there’s no such thing as right and wrong, only consequence.

.

CA: You dealt with that a lot in the first body of work, the Barbie & Me (2015) series. Tell me more about that.

TP: I think that’s quite a domestic project, because it is something that is in your home. It’s just about the daily things of growing up in a secular society. Not only trying to help myself understand but also trying to make everyone else understand that we do struggle. You know, it’s the small things that make life a little bit harder sometimes, and it would be nice if people could maybe be a bit more empathetic towards us, because especially now you find there is zero tolerance towards anything that doesn’t conform to secular ways. We do try, and I think if people understood that we do try, then we wouldn’t be seen as always trying to instill our own beliefs. You know, you hear things like ‘here they’re coming’, you get this kind of attitude now.. like ‘they are going to come and bring their ways here, and try to instill their beliefs here’.

.

CA: Force women to wear hijab..

TP: Yah, force women to wear hijab, and why is their mosque so loud? You know in Bo Kaap now the mosques have been asked to lower the calling to prayer, because there are so many foreigners who have moved to the area..

.

CA: But that is the fabric of that part of the city..

TP: I know, exactly. So it’s these kinds of things.

Barbie & Me Series, 2015.

CA: That is exactly the thing that people everywhere seem to be so afraid of, that Muslim immigrants will come to their country and try instill their radical beliefs, but here there are foreign people moving into a Muslim area and trying to impose their own wants and desires on to the area.

TP: The sad thing is that in our own spaces we are now becoming the minority. So this is what I address with the work upstairs, the idea of always being the minority, of always being invisible and always being unheard.

But going back to Barbie & Me, this is sort of my daily conflict, just struggling with small things. I always say that something like banking is such an appropriate example. You can’t get a job without having a bank account, but the entire banking system is Gharaam to us, because we don’t know where our money is being invested. It could be invested into arms dealings, or alcohol companies, whatever we don’t agree with. We are not allowed to invest our money into anything that could potentially be harmful to humanity. Every time we swipe our card, I’m thinking, did I just kill a child? And I know it sounds extreme, but this is the reality of the situation. I think it’s just about also being conscious, because these things aren’t only relative to being Muslim, but maybe it is just a sort of consciousness we are brought up with that allows us to feel bad within this space. So even something as simple as putting a scarf on, you asked me earlier, sometimes I am conscious of it.

Barbie & Me Series, 2015.

CA: If you’re going to the mosque for example, how many women would be wearing a headscarf?

TP: In the mosque everybody wears a headscarf. But then they take it off, well some, well I do.

.

CA: And does that make you feel guilty when you’re walking out and you’re taking off your headscarf?

TP: I guess it does in a sense. When you’re walking through the mosque it’s out respect for the space, it’s not about anybody else. But when you go out, then it’s about others. You do, you’re kind of conscious about these things. It’s a hard place to be. So yah, that’s what Barbie & Me is about.

.

CA: You’ve said before that raising boys in a secular society is difficult enough, but would you be more concerned if you had girls?

TP: No, I don’t think so. We all have challenges in the space. I don’t think it’s actually so much about gender. I do think that it’s just about maybe being Muslim right now. I mean, my little boy who is eight years old, asked me the other day, I don’t know if I told you, he asked me in the car, “mum are we bad people?” And I said, why? And he said, “because why does everybody want to kill us? Like, all the good guys, like the presidents and stuff, they all want to kill us. Why? Are we that bad?” And I just sat there thinking gosh, how do I explain this to him? You know, he’s only eight years old. And I had to explain to him that ‘no, we’re not bad, Trump is bad’ (laughs). You know, and trying to make him see that it’s not just us, it’s also Mexicans. There are lots of people out there who have done nothing wrong. But they watch movies, they watch cartoons, and they come to these conclusions that these American presidents and figures are the good guy. And then there are the bad guys, and the good guys want to kill the bad guys. You know, there’s this sort of, I don’t know, recipe (laughs).

Portrait of Motherhood, 2016-2017.

CA: When I first saw the Barbie & Me series they were just photographs, and now you have reworked them into tapestries.

TP: Yes, because of taking it back to the domestic space. Actually they are prayer mats. A prayer mat is something you will find in everybody’s home. Even if you don’t pray, you will always find a prayer mat. I mean, I have friends who are anything but practicing , but they still have a prayer mat in their house, just in case one day they are going to need to pray. So it’s about the consciousness that is always at the back of your head, no matter how you live, or what you choose. I know people who were born Muslim but now they’re Buddhist, and they still keep their prayer mat because deep down they know that one day they are going to need it. It’s something that never falls, it never goes away. It’s something that is within yourself. I don’t know, it’s your inner conscience.

.

CA: You have come to an art career quite late in life…

TP: (laughs)

.

CA: ..especially when we look at home many fresh graduates in South Africa are walking straight out of university and into a solo show with an art gallery.

TP: Yah, that’s true.

.

CA: But looking at this exhibition, what I found interesting is that in a very short space of time you have matured, from the Barbie & Me series to Remnants, upstairs. That’s a very short space of time to maturity that you’ve had to go through. For these younger artists it might take five to ten years to do that, and you’ve had to do it in, two years? Do you feel like you have to play catch up or that there was a lot of pressure on you to have done that, or do you feel that it was just a natural process?

TP: No, it was just a natural process. I think, I was not working for so long, that when I did start working I just could not stop. I was like a train just with no stops. It was like one-way to Simon’s Town. Everything inside was incubating.

Queen Colonaaiers and her Weapons of Mass destruction, 2015.

CA: You’re a wife, and a mother with three boys, and you have responsibilities that many younger artists don’t have yet. How are you finding the time and the energy to give to your practice?

TP: Gosh, I don’t even know how to answer that question. I’m quite lucky, I guess, because my husband is extremely supportive, and he pays the bills (laughs).

.

CA: He looks like someone who just loves being a father. He often talks about how much he loves being with his boys, and I see him all the time going past on his skateboard with the little one on the board with him and the other two following.

TP: Yah, he really is, I could not do this without him.

.

CA: In your opinion is that rare? Because the perception you have from a ‘western’ point of view is that Muslim men are not involved in raising the children, that it is the women’s job?

TP: No, I don’t think so at all, and that is one of the reasons why I wanted to stay away from gender politics. I had not come from a home, or place, and especially in our community, you know, the Cape Malays as we say, I never found us to be patriarchal or anything like that. People had their roles in the family, but I think it was chosen, and often the mother wore the pants in the house. I mean, I have two uncles and a million aunts, and the aunts rule. I have six sisters and one brother. In every space I have lived, the women have always been dominant, in everything, so I find it very hard to relate to this idea of Islamic men always being oppressive or all these things. It was not something I ever witnessed or was ever victim to, in a sense, not with anyone I grew up with and not with my husband. Although my husband was raised Catholic, he only became Muslim after meeting me.

Saman, 2016.

CA: Tell me about history and memory in your work.

TP: The reason why I draw on our history so much is because I try and stress for how long we have been invisible, and how wrong history is. How badly history has portrayed us, and in a sense how history has betrayed us; betrayed our legacy and our past, and so I try and re-address history. By doing so I hope to instill a sense of pride within myself and within my children. I’m not talking for other people, but I think I try and create visibility for the invisible, for whoever feels invisible, in a sense. When I arrived back in South Africa after living abroad for so long, I felt robbed, in a sense. Because I came here and I felt like we were not noticed, we were nothing, and I felt robbed. So I decided to delve more into our history, although I knew a lot already from my father because he had done so much research. I felt a need to re-align ourselves with something other than slavery, because firstly, my lineage were never slaves, we were free, you know, Tuan Guru was imprisoned as a political exile on Robben Island for seven, or twelve years, some people say seven, some say twelve, and then he lived in Bo Kaap as a free man. He was an incredibly influential man and he contributed largely to Cape Town and to what Cape Town is today. We would all be speaking Afrikaans today if it wasn’t for him, because he was strategic when it came to the Dutch and the English. He had joined forces with the English to help get the Dutch out, because we were a third of the population. So if we had gone with the Dutch, they would have still been here, but he bargained with the English who allowed us to keep our religion when the Dutch wouldn’t.

I am Royal. Self-Portrait, 2016.

CA: That is really interesting because obviously white settler history has been written about and recorded, and in the last twenty years there has been an effort to redress black history that was written about incorrectly, and so you are having to go into your past and present these stories of history that haven’t been recorded. Who were you speaking to, who were your sources for information?

TP: I have friends who helped me a lot, one was doing a PhD in History in the other was doing a PhD on Islam in South Africa. Also just reading a lot. The Indonesian Embassy helped me a lot and also my father, because there isn’t a book on the Earth that he hasn’t read. So I have collected information from lots of places, but it was always the same, it was always the same story, which made me feel this is good. It’s accurate, you know, it’s the real thing. Why I chose to do something called I Am Royal (2015) is because it is the complete opposite of ‘I am a slave’. More than anything, it stresses the distance of how far we are from our history, you know, we are actually on the opposite end. So now I walk around and I tell my children, guys, you come from royalty, and they love it. They go to school and their friends ask me, ‘is he really a prince’ and I say yes (laughs). But it’s funny, because it changes the way people feel about themselves. I can see it in myself and I can see it in my kids. If I had to keep telling them every day, you know, boys, your great-great-grandfathers they were all slaves, they’re not going to feel good about their past. Some of it they’re going to want to bury. The sad thing is that, ok, there were a lot of people that were enslaved, but there was more to them before. They didn’t start their existence through slavery. They also have a past, a history, we all do. This is something we need to start drawing on. It is something older than our colonial past, because we are all older than our colonial past. Look, colonialism, in a sense, did give birth to us, because that is the reality that I think I try and conclude with, that’s what I face at the end of my show. That’s the big question mark. But after I did all this work, what I’ve realized is that it is a journey where we start by aligning ourselves with something more than colonialism. For us to truly understand Africa, the contemporary world and the diaspora we need to look at globalization and its ongoing effects. What we need to then accept at the end of the day, is that yes we are a product of colonialism, but we don’t need to be ashamed of that. What we are now is actually indigenous; we are a mix of everything that has come. Maybe that is the difficult part, is accepting that, that we are all the same, in a sense.

In order for me to do Remnants I needed to do I am Royal first – it has been a process of personal development. Through reclaiming my heritage in that series of work I could go to India as a whole person. I was ready.

.

CA: You had a different experience when you went to Surat, and your experience of the legacy, or how do I say, the erasure of colonialism?

TP: Yes, I thought it was amazing. Surat is the oldest port and headquarters of the Dutch East India Company in India, the very first multi-national corporation. The reason why I went there was to confront history in a sense. I decided to go to the burial sites and mausoleums of the men and families who were instrumental in bringing Cape Malay people from Indonesia to South Africa, as well as moving and enslaving people from India, Ceylon, Madagascar and other regions surrounding the Indian Ocean, in the hope that being there would reveal the hurt and pain that does not go away after generations of being displaced. When I went there though, we were looking for these mausoleums which are massive, I mean, it’s huge, and it’s in the middle of town, but no one knows where it is. We were literally standing across the road from it, because the walls were quite high and there are a lot of trees, so we couldn’t see, but we were right outside of it and no one could tell us where it was. And no one could speak English, for a place that was colonized for around two hundred years or something, no one could speak any English. There was no English text anywhere, only Gujurat. It was amazing that they don’t hold on to anything from their colonial past. They’ve just moved on, as if ‘we don’t need this and it’s not a part of us. This is what was enforced upon us and we choose not to go forward with it’. It’s like it doesn’t exist. What was so amazing is, I don’t even think it was conscious to decide one day that they would take down all the monuments. I think they just couldn’t be bothered. I think they just knew, without thinking about it, that their lives didn’t need it and they just moved on. I found it so amazing, because here we are so primitive in a sense, where we are still struggling with these things, all of us, including me, we are still struggling with this past.

Bahasagalaramashari, 2017

CA: Why do you think that is?

TP: I guess maybe, I think because we are broken. I don’t think Indian people are broken, you know, they still have their culture, they still have their heritage, their history, traditions, they still have their ceremony, they still have their language, they still have all of those things, which we don’t. But also, we are a diaspora, all of us, and I think that’s the difference. That is their land, and they have remained on their land and they haven’t been moved. I mean, a large majority of people were displaced and migrated, but not everyone, it is still India. There is no place in India where you can go, like Cape Town, where you don’t see any African people. It is our reality, and it’s a sad reality, where you come to Cape Town and you don’t see any black African people. We are more like Australia, where so many people have been displaced that there is no recollection of anything authentic anymore. That is what we lack, is authenticity, there is nothing authentically African in the way that what we understand Africa to be. What has now become authentically African we don’t accept, because it is not the image of Africa that we understand. What the new image of Africa is, is us, it’s all of us. But we don’t accept that about ourselves. I think half of us feel like we can’t call ourselves that, because we don’t feel that we are worthy of the title here. I find it problematic, not so much for me, but for my kids, I don’t want them to still feel like they are unworthy of calling themselves South African. What is it to be South African? Even me, I still don’t feel fully that I am worthy of the title because I don’t understand myself. But what we actually need to realize is that we are indigenous. We have been formed here. The problem is that we still have a long way to go. It is not just about us seeing it, but about other people seeing it as well. The difficult thing with being in the middle is that you are neither white nor black. Black African people have a spiritual connection to the land, their ritual and ceremony is connected to the land; and white people own the majority of the land, so they have the financial tie to the land in a sense, they have that entitlement, the ownership. But we are sort of stuck in the middle of nowhere.

BAQA (video still), 2016.

CA: Tell me about ritual then, because you created an installation that was connected to ritual and smell as memory, not connected to the land itself.

TP: The thing with that particular work, BAQA (2016), is that once a year, since we were brought from Indonesia in the late 1700s, on the Prophet’s birthday, we collect citrus leaves, we smoke them with Frankincense, then we oil them with essential oils, and put them into little bags that we gift it to each other, usually the women to the men. This smell we then carry home with us, we put it in our clothing, and it stays with us until the following year. It is something that has been practiced literally since we arrived. For me, what it symbolizes, or what it represents, is that you can take away everything from people; you can take away their land, you can take away their freedom, their homes, everything physical, but the abstract things inside you they can’t take away. So it is almost a representation of the spirit that you can’t break. And also community, because everything comes down to the love for something larger than we are. It is this divine love that binds people. That’s where people draw their strength. You see it throughout Africa, I think that is why the churches are always full on a Sunday, it’s because people start drawing on something larger than who their slave owners were, and who their bosses are. That is something that no one can penetrate. It is something abstract, something that reflects the human spirit. When the human spirit is alive, there is nothing you can do to take it. You can beat the shit out of a man, but you won’t break his spirit if it is strong and he believes in something larger. That is what the work reflects; it really speaks about things that you can’t take away.

With all my work, I try and concentrate not on our weaknesses, but our strengths, because for far too long it’s always been about weakness and I’m tired of that narrative. We are strong. We are equally strong. We may not be visibly as strong as you in the sense that we don’t own lots of things and we don’t have lots of money; we’re not sitting in Zuma’s seat or whatever; but there are other strengths we have that may be less tangible, but are equally as strong. So when you smell that, it is a smell that has carried itself for hundreds of years. That is amazing! That scent has literally travelled the oceans, and come over, and has lasted the test of time. Even though our faces have changed, our hair has changed, and our eyes have changed, but these things have stayed the same. Even though we have all changed, there are some things that you are not going to take away from us. So I love that, I love that work. And I find that people’s reaction to it is amazing. Most people, when they walked into the room they didn’t know what it’s about and they just sit. The first time it was shown at the Cape Town Art Fair in 2016, and you know the Cape Town Art Fair, it is just mad. But people sat there for ages, and they were calm, and then they would say ‘what is this about?’ But first they would calm themselves, and they would be affected by the smell in such a positive way, and when they were ready they would come to me. When I told them, they would take the story in a different way than if I would have told them the story first.

CA: Smell is also one of the strongest links to memory.

TP: Yes, it is, so that is why, out of all the rituals, that is the one I chose, because of the reminiscence of it, the memory of it, and you can’t just remove things like that from people, it doesn’t work that way.

CA: Then on the opposite end of the spectrum, you did the Saman (2016) work and you had to learn the dance from an American girl on YouTube.

TP: Yah, that was quite funny. And this is what this all comes down to, this is what I keep saying, it was much harder for me, harder than anything else, the fact that at the end of it all, is the acceptance, that we are not what we were. Even though we are holding on to all of those things, that displays our strength, in it there is this irony as well, because it also displays this confusion, a lack, or a serious, I don’t know, like an identity crises. It is like an identity crises in a sense, because we are holding on, and it’s a bit of a pick ‘n mix, but what are we? And I think it is most evident in the Saman, it is a work made up of multiple images where I sit on the mausoleum floor in Surat and I did this dance. I remember Saman as something my grandfather and his friends used to talk about, and my uncles used to do, and they would go into a very deep, transcendental state through repetitive chanting and drumming, and then they would kind of lose consciousness. I remember it being very powerful in that sense. But when I Googled it, because my grandfather is not around anymore, and it’s something I just couldn’t find in time. I know it’s out there, but I couldn’t find people doing it in time, and I think that possibly comes down to the three kids and husband (laughs), I’ve got to work fast! So I Googled Saman, to see if I could find a group in Cape Town that does it, and what I found is that Saman is completely different to what we thought it was, we have remembered it differently. Originally, it was a dance of a thousand hands, so I had to teach myself this original Saman, but I had to teach myself from a YouTube video that was done by this American girl because the Indonesian girls were just too fast for me. I was so frustrated, but at the end of the day, I think, the performance of actually teaching myself this was in fact the most powerful part of the work, because once again it stressed how far removed we are from that.

It also brought the conversation back to globalization, that is what it all comes back to; that was the beginning, you know, to actually keep talking about colonialism and to ignore globalization, it doesn’t make sense. We are in fact a product of globalization, all of us, everybody, the whole world. What we see now started back then with colonialism. It’s actually just one massive movement and it hasn’t stopped, it still continues. But that was quite hard for me, realizing through that, what am I, who are we?

Maybe we need to all stop feeling guilty for calling ourselves African. We ourselves need to accept that. And if we accept it then other people will be open to accept it. I think that is what it actually comes down to. Unfortunately everything has been reduced to material stuff, but if we look spiritually to within ourselves, the feeling of not feeling worthy is more than material acquirements.

I think we have a long way to go, but saying that, we are still at the forefront of progression, as far as the world goes. Because when I look at everybody else, they’re not talking. At least we’re talking. I find that especially with the arts, you know, art is a healthy place because people are angry, and it’s ok. They are supported through their anger, people watch them, they come, and it’s ok. We are all angry. I was angry with I Am Royal, I was not angry with Remnants, now I’m just confused. Now I need to work on my self-worth. I think art has been a very healthy way in which South Africa has been dealing with these issues.

God Save Our Hedge (Botanical Imperialism Series), 2015.

CA: What next?

TP: I am working on something, actually, but it’s still baby steps… maybe I shouldn’t talk about it yet. But it’s a performance; it’s a performance about.. ok, I’m not ready to talk about it yet, because it’s going to change. But it will be at Rhodes University.

.

CA: Rhodes is a very contentious place.

TP: Absolutely, and with performance site is important, well my performance especially, site is very important. There is something about being in a space that is important, physically connecting in the space, because once again everything comes down to land. So connecting with land in a specific space needs to happen in the performances. I was invited to spend a month there for a residency, but I’m a bit scared, because I’ve never left my boys for so long.

.

CA: Well this is the reality of being an artist and a mother.

TP: Yah, it is, I mean this is the first time I have ever entertained the idea of doing a residency. I don’t know if I would be able to do it, I went to India for ten days and I cried my eyes out. That’s why I look so miserable in my work, people think it’s about confronting history, but I’m crying for my babies (laughs).