Africanah.org at 5: We celebrate the 5th anniversary of this magazine with the re-publication of a number of remarkable essays. This article of the South African artist and writer Thuli Gamedze was published in April 2015. It talks about the student protests in her country in that year. On a general, even universal level however it talks about the correction of the history by tearing down monuments that were once made to hero-ize a person or an event, but that now can and must be seen as symbols of a malign colonial system.

Thuli Gamedze challenges colonial and other monuments.

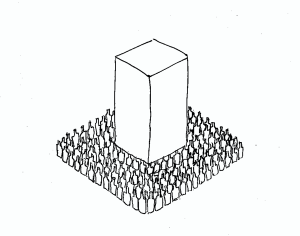

Detail of a site specific work of Lungiswa Gqunta.

To Hell With Monuments

Exploding the Monument and Considering Radical New Ways to Occupy Public Space*

A new conversation has rapidly emerged in the past while, articulating, in various ways, that the notion of the monument is one that needs to be challenged and re-understood in the South African, and global context now. However, I think this assertion quickly glosses over the kind of institutionalized and seemingly inherent place that the monument, as it has been defined by outsiders- settlers- has in colonial society. What makes the monument, what forms its valued place-ness, and would it perhaps be more useful to try to uncover the power relations forming the very notion of ‘monument’ before attempting to transform it, liberalize it, democratize it, or diversify it?

As I see it, any solidly defined, articulated and aestheticized representation of the now, that is privileged enough to presume it’s relevance in the future, is a dangerous object. As we have seen through multiple 2015 student protests, where many of us were conscientized through mobilizing around the violence of colonial symbolism, a monument is not simply a representation- it gives strength to the static, it validates regime, and affirms its own position in an attempt to prove timelessness. While the monument still stands, so then does the status quo it holds.

I suppose in trying lose the monument trope, what I am attempting to speak against is the naturalized place it has come to have in society- when we want to publicly commemorate, celebrate, or bring together, the age-old response is to construct a monument. Of course, colonial societies such as South Africa are now littered with contemporary versions of this idea that depart from western material forms of public work, but are still informed by a very binary and idealized understanding of how humans collectivize and relate to one another. I would argue that the monument has nothing to do with human collectivization, commemorating or coming together, and has only to do with an epistemological securing of dominant ideology. So we should ask whether there ways to manipulate everyday forms of living- forms that depart from the status quo- such that these become ‘monumental’? How can ‘other’ living and being practices become the central factor of new monuments? How can we give voice to monument action, prizing what the monument creates above what it imposes? And what happens when we do this?

So, to start, we are forced to engage with the notion of the monument as it stands, and of course too, we must conceptually pull it apart, imagining new ideas that we would like to occupy public space. However, if we do this with the idea in mind being to replace, we give ourselves very little space in becoming and in doing so we begin to validate a colonial action by mimicking its process of making power into object, and allowing object to be central in securing static ideology. This action of making monuments, even as current/ liberal as the particular ideology they represent might be, fits far too snugly into colonial society. It is not objects that are the problem, and neither is it power or ideology. It is the monument’s relationship with these entities that gives it the elite position it has in colonialist structures. This position seeks to still time, and asserts itself as having proud and never-ending value.

Lungiswa Gqunta, Sketch for a Sculpture, 2016

The nature of the ‘New Monuments’ exhibition at Commune 1, Cape Town, engages with the possibility of the monument ‘object’, and attempts, through multiple ‘proposals’ for new monuments, to push and pull the monument’s form, working around but within its constraints to find out whether in fact, there exists ideology or principle worth concretizing, even temporarily, and whether an object can function as a catalyst for ideas, rather than as a solidifier of ideology. The exhibition includes work that experiments with the materiality of the monument, including a sound piece by Caitlin Mkhasibe, that gives voice to new ways of making monuments, but more importantly, new ways to view or listen to them. In this sense, the monument asks the viewer to read different, creating potential new pathways that are gradual in the slow burn of the principle of monumentalisation itself.

We can attack the monument principle from many directions but central to this is the necessity to re-situate our viewer or our reader to a position that sits outside of the pre-determined relationship structure of human to monument- a relationship that defines acts of remembering, relating and celebrating as static acts, rather than as acts that are performed and that keep changing, actual actions. Of course, one such method is through materiality- as in Mkhasibe’s work, where we must listen, instead of looking at the thing which automatically allows us to relate to it in a changed way- but how else have ideas occupied monument spaces in ways that allowed them to speak more to what is held outside of the monument, rather than what is held within?

Shackville and ‘Action-Monuments’

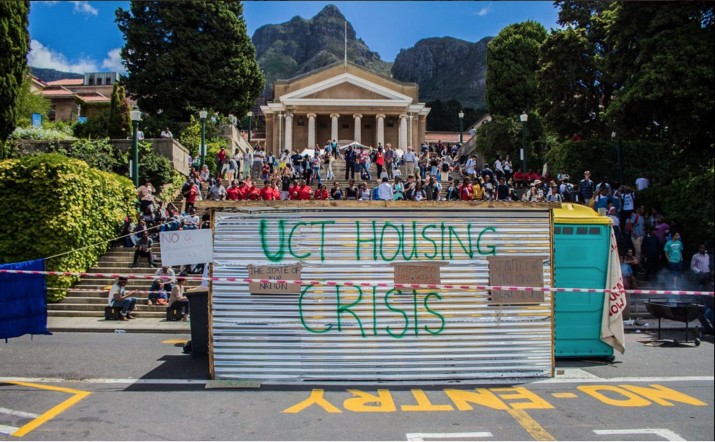

Shackville, 2015.

The RhodesMustFall movement created Shackville earlier this year, an intervention in which a shack was erected on the University of Cape Town’s upper campus. Disrupting traffic and campus activity, the Shackville intervention quickly caused much drama, anger and controversy between university management, who wanted the shack to be moved out of the way, and Black students, who had no reason to move until their demands were met. This refusal to move lead to a second intervention, where police brutality was inflicted on Black students as instructed by management forces, which then lead to a third, in which colonial paintings and photographs, a university vehicle and a bus were burnt by protesting students.

Speaking to the issue of UCT’s ‘housing shortage’, it’s failure to give accommodation to a large number of Black students, the intervention brought the supposed ’un-institutional’- South African poor working class living conditions- to the institution, making evident the oppressor-oppressed relationship of dominance between white institutional culture and Black poverty and exploitation. While Shackville stood strong as a strategically placed sculptural piece, what ensued around Shackville became the action of the intervention, and by extension, the action of the larger Shackville situation in South Africa. Shackville became not only a comment on institutionalized oppression, but an enactment, and a catalyst for the exposure of it. It created a scene of state brutality, and reaction, and functioned as live ‘performance’/ reality of current politics in Cape Town and South Africa, articulating through this the power of the action of monuments.

Rhodes Memorial Cape Town.

The work poses questions around who is allowed make monuments, and when the marginalized do make monuments, are they bound to be disruptive, and create action? The Icelandic pavilion at last year’s Venice Biennale serves as another ‘new monument’ or ‘action monument’- the work was an old church building that was converted into a functional mosque. Initially formulated as a response to an old monument- the church- the intervention functioned as ‘symbolic’, a responsive monument in a way, standing to articulate the lack of necessary infrastructure on the island for the practice of Islam, and highlight what this says epistemologically, as well is in much more practical senses, about Europe’s relationship with the religion and it’s people.

However, because the monument functioned as a space, the inevitable result was that the space becomes occupied with religious practice, and essentially its object-ness became less and less relevant in the face of its pure functionality. Similar to Shackville in the way that the work protested for a basic human right and pulled people to act in relation to it, the space was eventually shut down by the police, due to ‘overcrowding’, and risk of ‘extremist threat’, but perhaps more accurately, because it had transcended the allotted boundaries of object-ness and become a space where oppressed bodies were free- a notion that is inherently disruptive to the status-quo.

I feel that here, we deal with the notion of ‘monument’ being unlearned and exploded into functional idea and space. This leads to me to the assertion that the ‘monument’ remembers, while ‘action-monument’ lives, and creates an ongoing historical trajectory.

To Hell With Monuments?

Lungiswa Gqunta’s sculptural work ‘To Hell With Monuments’ articulates this essential idea: monuments cannot serve the oppressed, and when the oppressed do make monuments, they rarely last as monuments, but begin to function as subversive actions. A part of the New Monuments exhibition, Gqunta’s work consists of petrol bombs that lie underneath their allotted plinth. In this physical positioning of the bombs, as well in the title, the artist alludes to the very underpinnings of what I attempt to assert here- there is no ‘other’ monument that can stand in isolation from ‘other’ bodies, and the way that we move and make sense of the world. And the way that we move and make sense of the world has been constructed as disruptive to the world. In this sense, the new (monument?)- let’s think on a new word for monument- creates what does not exist, where the old monument asserts and concludes what does.

So- to hell with monuments.