“One of the aspects that I love about your work is how you use the archive, and time you spending going through the collection. You understand the importance of the visual archive because you want to examine how it reshapes the past. In addition I am interested in how you identify, locate and preserve these photographs and visual narratives. You take the text away from the advertisement in order to bring forward new information. You have this combination of not only locating the actual image, but you are also preserving that image and preserving a memory.”

Deborah Willis on the work of Hank Willis Thomas.

Hank Willis Thomas

Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915 – 2015

The archive is what becomes past as we move toward the future, and its boundaries ‘deprive … us our continuities.’ The way we access the archival past, Foucault tells us, is through motions that are at their base archeological – sifting and combing through things already left behind.” (1)

Michael Foucault

Hope and memory have one daughter and her name is art (2)

W.B. Yeats

When Hank Willis Thomas attempts to answer arduous and vexing questions, he begins with research. I have been impressed with his inquiring mind since his pre-K days as a student at the West Side Montessori School in New York City. He was fascinated with billboards, especially in Times Square and on the New York subways. He was not only fascinated with the images but also the messages found in them. He writes “I got my first pair of Nike shoes somewhere around 1981. I was five years old. At about the same time, I learned I was black. At that age I saw no connection between these two revelations. Eventually that would change. My shoes were blue canvas with white leather “swooshes” on both sides. They had blue suede patches at the toe and the heel. I remember examining them one night as my mother and I rode on a graffiti- covered New York subway train. I stared at the shoes with amazement. Something about them was special. I asked my mother what the word “Nike” meant. It was written on the back of the shoe. In that early stage of learning I had never seen that word before. She didn’t know its meaning. I asked her what the white designs on the sides of the shoe meant. She didn’t know the answer to that either. I asked a lot of questions in those days… About four years after my first purchase of a pair of Nike shoes my mother and I were at a Footlocker store in a New Jersey mall. I will never forget the first time I saw them: Nike’s Air Jordans. All I can remember thinking was “Wha” ! How did they invent such a shoe?” They are hi- top sneakers with a drawing of a winged basketball on the back and Nike Swooshes on each side. And as if the style was not cool enough, the display rocked my nine-year old word with a giant poster of a black man wearing the red shoes frozen in mid-air ! … I don’t think that I have ever wanted something more than I wanted those red shoes (red magic slippers). I was heartbroken when my mother told me that we couldn’t afford them. I could get another pair of cheaper Nike shoes though. I was bitter. There was no picture of anyone flying or even jumping high in any other pair of Nikes. Wasn’t stupid though. I figured that I would just get a cheaper pair of Nike’s such as Air Pegasus (named after the winged horse in Greek mythology), and they could act as training wheels for when I got bigger and really needed shoes that could help me fly.”(3)

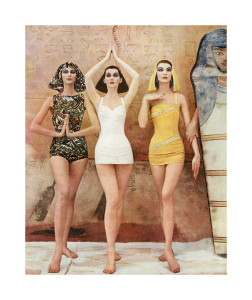

Da’Nile, 1956/2015, digital chromogenic print, 2015.

Da’Nile, 1956/2015, digital chromogenic print, 2015.

I began this conversation with my son with his own words as they guide me in connecting to Thomas’s inquisitive mind. Thomas’s work is about memory and not forgetting. His work is a cautionary tale about remembering the past and helps us to reimagine periods in history that gave us slogans such as “Beauty’s reward,” “ don’t wear a tired thirsty face,” “women and carrots have one enemy in common,” “ at last I’m Free,”and “she’s all tied up in a poor system.” Thomas redacted such benign and caustic phrases from the images and in his quest to ask questions as to what is being sold he leaves us with imagery that offers us a view of the business and culture of advertising from the early twentieth to the twenty- first century. Thomas’s works inform us of multiple stories about identity and how desire is suggested through such images. They also help us see and question what stories have been told about humanity through advertising.

*

Thomas’s earlier exploration in unearthing images from advertising history began with the Branded Series in 2002. Followed by Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968 – 2008, which looked at ads focusing on the black consumer and black subject. It is comprised of photographic images he appropriated from magazine advertisements marketed towards an African – American audience and / or that featured Black subjects. The project presents two ads for every year from 1968 through 2008. He “unbranded” or digitally erased all advertising information. No other part of the image was altered or digitally manipulated. These images informed the contemporary viewer about attracting and selling products as well as shaping cultural identities through the collective mind of Corporate America.

*

In Thomas’s most recent series Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915 – 2015, he introduces the viewer to drawings, paintings and photographs that captured a variety of imposed identities about White women during a period of time that shaped the role of women in the public’s imagination. These images conflated the image of women through the construction of whiteness as privilege and innocence; enjoyment and pleasure; leisure life and work; inhibited and immoral. These works also serve as a narrative of significant moments in history between the war years, specifically between the First and Second World Wars. And also look closely at the home front during and after World War II.

*

He makes searing connections to the plight of women during, before and after the Depression years and later through the activities of the women’s rights movements. Thomas chronicles these visual representations as they reform over time in accordance with social, ethical, cultural, political, and economic shifts in American history. This provides a spectrum of reference for the ideal feminine ‘type” that has been marketed to individuals across gender, race and socioeconomic lines for centuries.

*

By doing so he suggests that the standard of virtue of modern women has been traditionally aligned with the image of White women in advertising. American women did not have the right to vote100 years ago. Today, we are possibly on the verge of electing the first female president. Many of the amazing shifts in societal perception of women’s roles over the past 100 years were documented, and sometimes instigated in ads. At the very same time, many confining stereotypes and generalizations have persisted and are increasing framed by America’s corporate agenda. By excavating and examining commercial photographic images of the past and pairing them with popular imagery of more recent decades the viewer is provided a temporal lens for better understanding the untold part of our shared cultural history.

*

Thomas is well aware of the importance of the visual record in understanding the past. His contemporary archeological dig within the digital files of outdated magazines helps us to reimagine the period in which the photographs were presented and created. By locating and preserving the visual stories of white women, narratives that often misrepresent women, Thomas interrogates, questions, and affirms what we think we know about the history of advertising. In addition these images shed light on the economic, political, social and cultural life of all Americans. They depict notions of pleasures; they suggest crucial reflections on American History.

*

This conversation with these thoughts to suggest that Thomas’s aesthetics offers another way of viewing the constructed ideas about what it means to rebel and become part of a Twentieth century movement for equal rights and social change. He also explores the ways in which corporate America used art and photography to focus on the idea of the American consumer being seen, as they desired to be seen.

*

Thomas focuses on the overwhelmingly large number of idealized poses that suggest sexual pleasure for men with women in submissive roles. There are also iconic images of abuse directed on the female body.

He collected over 300 advertising images of “White women” as part of his initial research for the project in an effort to track the construction of a “white, female, American” identity from the final days of the suffrage movement on to the future. In doing so he highlights the effects of stereotyping, while posing provocative questions regarding these images that empower and disempower. The resonance of these images, many of which have become emblematic, extended beyond the meaning of its original purpose. With the absence of the text they take on another form of social and historic meaning. In an interview with Time, Thomas says, “Part of advertising’s success is based on the ability to reinforce generalizations developed around race, gender and ethnicity, which are generally false, but {these generalizations} can sometimes be entertaining, sometimes true, and sometimes horrifying.”

Safe, sound and dewy eyed, 1957/2015, digital chromogenic print, 2015.

In my view Thomas transforms us through this experience. Thomas believes that advertisements are bellwethers.”They not only reflect the values of the demographic they are speaking to, they also inform us about how we are positioned within the cultural and economic framework. A single ad can tell us a lot about a society’s hopes, dreams, and fears. Mass- produced ephemera are some of the most telling archival material, but also some of the most quickly discarded by historians. In this age of hyper-saturation, I think it is important that historians and artists alike think critically about the images that we as a society are producing and circulating. By “unbranding” advertisements I encourage viewers to look harder and think deeper about the empire of signs that have become second nature to our experience of life in the contemporary world.”

Deborah Willis: Your work informs the audience that there are many stories about identity and desire. It also helps the viewer see and question what stories have been told about humanity through advertising. How did you begin this new project about advertising’s role in shaping the cultural identity of White women in America?

Hank Willis Thomas: This project began with an e-mail that was forwarded to me that showed sexist advertising. You might have sent it to me. I was fascinated by the level of violence in these ads that featured primarily, or exclusively white women from around the 1930’s, 40’s, 50s and 60s. I thought about it for a while and realized that this period where white women frequently visualized in dehumanizing and sexist ways was also the same time when people of African descent, like Emit Till, were killed for merely looking or whistling at a White woman. This body that was so precious in one context was also being policed in very specific ways in another.

DW: That is fascinating. We see one aspect of the White woman as protected through the history of the Ku Klux Klan and other movies and literature about the South, through images of slavery, and the fear of looking at a White woman in the tragic example that you mention with young Emit Till. However, advertising creates a counter- image, a stereotype, and through stereotyping the aspect of desire is explored through the marketing of these images to a large, diverse, community. Again, why White women? Why not trace Black, Latin, or Asian women and their images in advertising? You have helped to define attitudes about Black Americans in advertising through your early work. And why explore this campaign in 2015?

HWT: I have done a lot of looking at blackness and what I have struggled with most about blackness is that it is a European construct. I always like to stress that the craziest thing about blackness is that black people never had much to do with actually creating it. It was actually created with commercial interest in order to turn people into property. The colonists had to come up with a subhuman brand of person and that marketing campaign was race. So much of the conversation about race is spent talking about blackness and Black people, but it does not, or rarely address whiteness. Whiteness was constructed to give certain people an upper hand, and we brown people have been contending with this oppositional hyperbole for centuries. Therefore this project focuses on the fabrication of whiteness. One hundred years ago many people that we now consider to be white would not have been. For example, Russians, Jews, Italians, Irish, Armenians, Polish, and most Eastern Europeans, would not have been considered white.

Whiteness becomes a kind of amorphous blob that people can assimilate into. Even many people who are Black have assimilated into whiteness over the course of these past one hundred years. I am interested in why people want to assimilate into whiteness. Then when I think about the “female body,” White women did not have the right to vote one hundred years ago, no women in the United States did. These valued, precious bodies presumably had very little self- determination. Now one hundred years later, a major part of the current political discussion is about electing the first female president, presumably the first white female president. I look at advertising as a means to trace this evolution through popular culture in advertising.

Just as our Forefathers intended, 2015/2015, digital chromogenic print, 2015.

Just as our Forefathers intended, 2015/2015, digital chromogenic print, 2015.

DW: One of the aspects that I love about your work is how you use the archive, and time you spending going through the collection. You understand the importance of the visual archive because you want to examine how it reshapes the past. In addition I am interested in how you identify, locate and preserve these photographs and visual narratives. You take the text away from the advertisement in order to bring forward new information. You have this combination of not only locating the actual image, but you are also preserving that image and preserving a memory.

What I see about your work is that you are not allowing us to forget and that is really important. Your work also affirms many ideas about life in general. What does the audience take away from this notion of whiteness, the fabrication of identities and the preciousness of the female body? Please talk about some of the ads you have selected to remove the text and the scenarios that you are recreating.

HWT: I thought that it was appropriate to look at 1915 and what was presumed to be the status quo. The series starts with a very popular Cream of Wheat campaign featuring, Rastus, a black servant offering hot cereal to Jack Sprat and his wife. That image is followed by a Kodak ad of a woman holding a camera, gesturing as a hunter of sorts, capturing the world around her. Photography was not considered an art form yet, it was seen as a tool of leisure. This image also elicits the idea of the woman as hobbyist.

DW: The woman in the Kodak ad is photographing a blacksmith. It’s normally the woman who is the subject. This kind of reversal in who is participating in the role of subject and object is really fascinating with that image.

HWT: Right. And then in 1920, we see women get the right to vote in the United States and there is an image of a woman driving a car – it’s for an upholstery ad – but you recognize that power is seen as being able to create your own direction in life. The driving symbolizes that. Then in a Palmolive ad there is the connection with Africa, through Egypt. Very near the time that King Tut’s tomb is found and excavated, this kind of appropriation of Egyptian aesthetic was becoming widespread.

Women’s hair gets shorter as they become more like “men” in terms of having more agency, freewill and decision making. Dresses get shorter, and women become more sexualized. During the Depression era you see women having to work but also masking this fact. There are also depictions in this time of women being served by the noble savage in tropical climates. By the end of the 30’s these women are now doing the “man’s” job- they are flying planes, they are business women, they are in soldier’s uniforms, they are in factories. It is fascinating to observe the same demographic over the course of these ten years change in advertising. White women are doing very serious physical labor until just after World War II when the ideal of the housewife returns.

DW: There is a great tension about the ads during World War II. Women were not only viewed as soldiers they were working in the military industrial complex, they were the breadwinners and making decisions about their lives. Now the male soldiers are returning home and there is a place where women should be within the home, so the ads are also restructuring the idea of how women should be seen. They are creating desirable places for women to work within the home, like the strange ball and chain Westinghouse ad, where the viewer sees slavery idealized and accepted in the domestic context. It’s constructed with a dress that has stripes that are similar to stripes that prisoners wore on chain gangs. And strangely enough, the ad shows a fully stocked refrigerator …therefore having a defrost button in your fridge gives one a sense of freedom.

HWT: It is a frost – free fridge, so she says “At last I am free”. The title is also a part of it. I’m creating titles from the language that accompanies the ad.

DW: What is being sold in the 1951 ad with a woman in a strait jacket?

HWT: The ad reads, “She’s all caught up in poor systems.” It is about business forms and bureaucracy. She works outside of the home presumably as a receptionist.

DW: What is really disturbing for me about these ads are the ones that include images of women after the 1950’s. There is a reference to violence both domestic and self-inflicted.

HWT: There is a lot of violence. In a 1955 ad for corsets there is a male body dragging a woman by her hair. The text reads, “Come out of the bone age darling.” By this time, women have served the country in wartime, and want to acquire the same authority and opportunities that men have traditionally held. Frequently, men are responding in a visually aggressive way to this notion, for example I have included a 1959 ad for sweaters that depict a man dangling a woman from a cliff.

DW: In the 1956 Kohl’s ad for bathing suits, we see the memory of Egypt again through hairstyles, King Tut’s tomb, and hieroglyphs.

HWT: One of the things that I see through the 1956 ad is the brown face painted on the tomb with Egyptian characteristics, while the hand coming out of the tomb appears to be that of a White man. We see the depiction of Africa using people with European characteristics. Even today, in the film Exodus all these Western Europeans play Africans. There is an erasure of “black history” and “black culture” in the appropriation of it.

DW: What is not being seen in your images is the text. How do you want the audience to respond to these images?

HWT: It is important to recognize that we are used to seeing these images with the text, and we don’t look at the images anymore. I want people to think twice about what they are buying into, literally and conceptually, when they buy a product. Advertising is a form of social conditioning and brainwashing. It is beautiful in its ability to communicate really complex ideas, but it is also sinister in its capacity to do that.

DW: What’s the good part about these images?

HWT: We see this battle taking place for agency and autonomy for women. The White woman starts to take a new role every fourth of fifth image. There is a fascinating one step forward, two steps back kind of oscillation among the series. It is a challenging project for me. I would rather not be associated with the overwhelming majority of images. It is weird to put your name on something that you actually disagree with in a lot of ways. The goal of making art is to provoke, to challenge and not necessarily answer questions, but hopefully to inspire really necessary conversations that are so often ignored.

DW: That is fantastic. Thank you. I see the power of your work. A number of your images have become iconic. You give the audience an opportunity to explore the messages in the images, to think about their meaning socially and historically. In so doing, you provide the viewer with a new way of constructing and reconstructing history through a sense of memory. I stated earlier, that your work is about remembering the past and the effect of racism, sexism, and xenophobia, as we think about how these ads are constructed. I really appreciate the fact that you are working in this vein.

HWT: Thank you. The work for me is really very much, as I have said often, following in your footsteps. It picks up where you left off in certain works with your books like The Black Female Body and Posing Beauty where you look at how the images that we produce , that are sometimes mundane or seem unimportant at the time, actually have a really powerful and lasting impact. I am really fascinated with the potency of the things that we ignore, and because they go under the radar they become more powerful in their influence on us.

DW: Thank you.

HWT: Thank you.

Notes:

1 Kellie Jones, Eyeminded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art, Durham: Duke University Press, 2011, p. 23;

2 The Celtic Twilight Author: W. B. Yeats Release Date: December 14, 2003 [EBook #10459];

3 Hank Willis Thomas, Swoosh: Looking black at nike, moses, and Jordan in the ‘80s, in Sight Lines Thesis Projects 2004, Graduate Studies in Visual Criticism, California College of the Arts, p. 2, 10.