These examples highlight the possibilities that art, and the process of being engaged in artistic activities, can offer an awakening conscience and awareness of citizens in areas of peacebuilding and how they encompass civic reactions to violence and conflict through calling for reconciliation and coexistence.

Craig Halliday on peacebuilding through art

Art-Based Approaches to Peacebuilding

As Kenya’s 2017 General Election on August 8 approaches, and following the chaotic primaries undertaken in April, some commentators have warned that this General Election will be violent and chaotic.[1] Since the re-introduction of multiparty politics in the early 1990s the country has repeatedly witnessed ethnic tension and violence around election time. Only the 2002 and 2013 polls stand out as being relatively peaceful. Nearly a decade ago the violence that erupted in Kenya between December 2007 and the end of February 2008 (following a disputed presidential election) left at least 1,133 people dead and displaced more than 600,000 people.[2] During this time there were cases of arson, looting of property, maiming of citizens and eviction of people from their homes. Following the post-election violence of 2007-2008 an array of peacebuilding efforts took place. These intensified again in the run up to the 2013 elections. Over this period artists used various forms of visual art to prevent, reduce, transform, and help people recover from violence. Peacebuilding expands across disciplines; however the field of the arts often receives less attention than other fields. Given the complexities of conflict and violence there is a need to adopt diverse tactics and tools that meet the challenges posed during peacebuilding.

This short article provides a brief overview of visual art-based approaches to peacebuilding that took place in Nairobi, Kenya, from 2008-2013.

The strategic what, when, where and who

A number of authors have argued that the arts can be used in peacebuilding due to their therapeutic role; as a tool for healing, expressing and describing fears, anxieties, and other feelings when talking or words fail or seem unsafe. Additionally it has also been claimed that the arts can be used to raise public awareness, to create ‘safe spaces’ (if only temporary) for a physical, emotional or psychological beak in the cycle of violence. Such approaches can provide a ‘transformative learning’ experience and lead one to see, or imagine, the world through another person’s perspective. The use of visual art forms can also be used to present uncomplete or indirect narratives, enabling people to draw their own conclusions. In doing so, this may come across as less patronizing compared with more formal approaches to peacebuilding. However, while the arts are asserted as powerful tools in peacebuilding, their destructive potential – due to their ability in opening underlying memories, emotions and trauma, or inspiring hatred and division – must not go unnoticed. As a result art based approaches to peacebuilding need be dealt with sensitively and engage in an ‘optimal tension’; too little and people will not be engaged enough to deal or confront issues of conflict and violence, though if there is too much this could threaten to escalate violence. These complexities require a strategic when to use art-based interventions (as the potential for conflict arises, during conflict, and as conflict diminishes). The when influences what approaches are best used, where to use them– in term of spaces of relevance and strategic social interaction – and who to target, taking into account who may be the biggest agents of change. By harnessing these different approaches art-based peacebuilding can have a transformative impact on peacebuilding efforts.

Art-Based Approaches during and immediately after conflict and violence

In Nairobi, the bulk of the post-election violence took place in the slums. The informal settlement of Kibera was a stronghold for Raila Odinga, leader of the oppositional Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) who had a robust patron–client relationship with Kibera’s residents. Following the results that Raila Odinga had lost the presidential elections, people in Kibera came out in large numbers to protest. Some began committing arson and looting. Violent confrontations took place between ODM supporters, and the police forces and supporters associated with incumbent President Mwai Kibaki and his Party for National Unity (PNU).

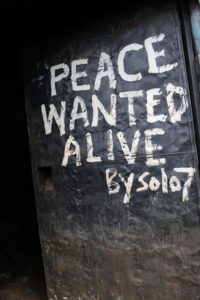

For artist and resident of Kibera, Soloman Muyundo (who goes by the name of Solo 7), something had to be done. Initially Solo 7 began writing messages of support for ODM on people’s property. He claims where he wrote ODM people would not loot there – seemingly demonstrating the power of slogans. In January Raila Odinga called for three days of mass action. Concerned that violence would intensify Solo 7 came up with a new initiative. Armed with a tin of paint and brush the artists began writing peace messages all over Kibera. These messages – which read ‘KEEP PEACE’, ‘PEACE WANTED ALIVE’ and ‘KEEP PEACE FELLOW KENYANS’ – were written on roads, walls, gates, electricity poles, buildings and fences.

Hundreds of, if not more, messages filled Kibera’s ‘public spaces’ and created a discourse of peace during a period when political negotiations had ended in failure. According to the artist the use of short and clear visual slogans were powerful because they “speak louder than our voices” and have a persuasive quality in that they force people to stop and think before acting. The work of Solo 7 shows that with minimal resources the activism of an individual can have considerable effects in creating a peace dialogue through peace slogans.

Solo 7, Kibera

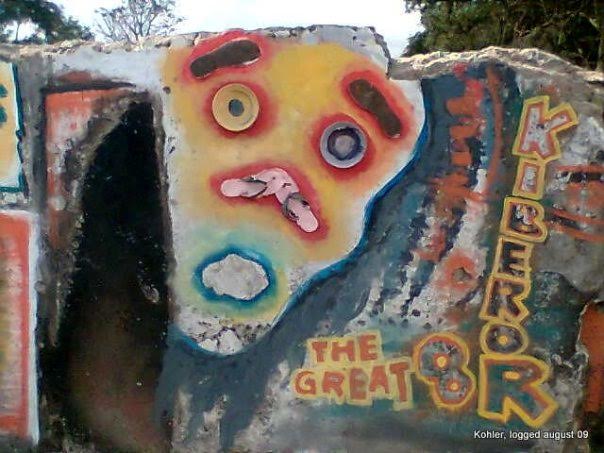

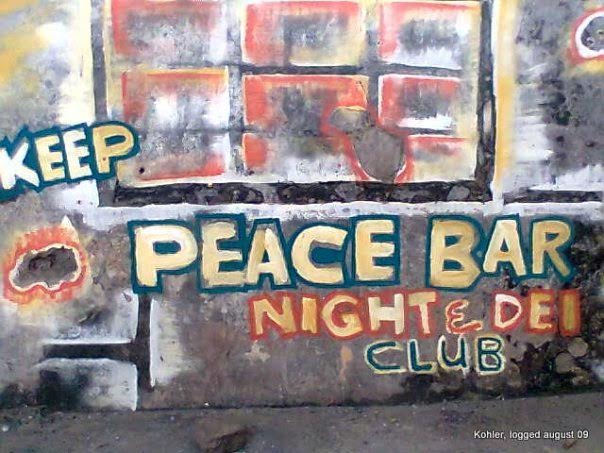

In an attempt to bring peace, a coalition government was formed between PNU and ODM at the end of February of 2008. This was largely successful in ending the violence. However the destruction was still visible and people were traumatized. Many parts of Kibera were left in ruins. The violence that had erupted in Kibera, and other parts of Kenya, had an intense impact on a group of artists based in Kibera, called Maasai Mbili.[3] These artists felt compelled to do something for their community. They decided to make a museum (albeit temporary) out of the ruins in Kibera in order to bring back harmony to the area but also to offer a space where children could come and express themselves and their emotion through painting.

Taking place at the end of February 2008 and lasting a few weeks the artists worked with approximately 30 young people from the area – many whom had witnessed some form of violence as a result of the post-election violence. The project used painting and the process of creating as a form of healing. Children were given art materials and encouraged to draw what was on their mind. Speaking with the artists involved in the project they describe how to start the children would paint events that had just occurred and memories still present in their minds. However, as the project progressed the artists describe how the participating children were painting scenes of what they would like to see, to be or to do. Through their art they were discussing future possibilities and hopes. Through painting the ruins the project was also changing the physical space. Through drawings, color and text, harmony was being brought into these spaces which gave them a feeling of value. In a sense they were re-humanizing the spaces seeing them for what they could be which was essential to the peace building efforts of the time.

Painting the Ruins, Kibera, Maasai Mibili

Art-Based Approaches as conflict and violence diminishes

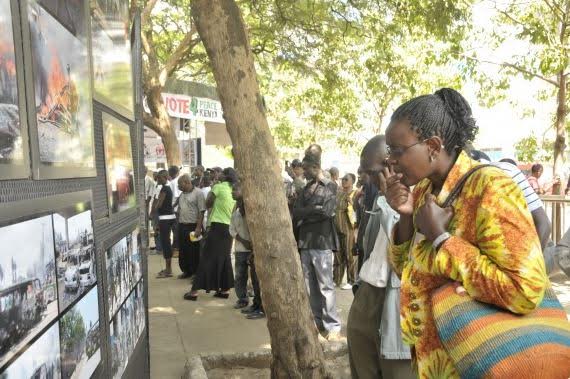

Two years on from Kenya’s 2007 General Elections the project “Picha Mtaani” was launched in Nairobi, during December 2009. Picha Mtaani, which translates loosely to ‘street exhibition’, created public platforms which initially exhibited photography taken during the post-election violence of 2007-2008. Many of the images were of a graphic nature or showed the violence and destruction that took place in Nairobi and other parts of the country. The project shared similarities to a photographic exhibition called ‘Kenya Burning’; ran by the GoDown Arts Centre which showed images, captured by amateur and professional photographers, taken during the post-election violence. ‘Kenya Burning’ was launched at the GoDown, Nairobi, in April 2008 and subsequent exhibitions took place at other venues in Nairobi, Eldoret, Mombassa and Kisumu. The exhibition provided an opportunity and space for audience members to reflect on the post-election violence.

Boniface Mwangi, the Director of Picha Mtaani, believes that photography is a strong medium as it captures reality in a genuine and unbiased manner. Though in reality I would argue that this is not true. Images taken or not taken are marred by photo journalists’ own views. As such the narrative they create through capturing and then arranging images to be presented to an audience is mediated and biased. However, that said Picha Mtaani and spaces in which the exhibitions were held did create spaces for reflection and conversation. In Nairobi the exhibitions took place in the Central Business District, the National Museum and Uhuru Park. The exhibitions also travelled to other towns across Kenya affected by the post-election violence. However the reception was not always constructive. For example in Nakuru police were reported to have disrupted the exhibition and confiscated images of police brutality.[4] In Kisumu it was reported that a group of youths pulled down the pictures and threatened to burn them.[5]

Shortly after these exhibitions, the platform of Picha Mtaani expanded to include elements of drama, counselling, group discussions, documentary screenings and the promotion of peace pledges for citizens to sign. It was envisioned that these activities would help to ease the tension created by the photos alone and would help to create dialogue among the populace in regard to the diverse issues that must be overcome if Kenya is to move forward to a more peaceful, stable and democratic society. The Picha Mtaani project confronted the past head, through visual imagery of the horrors of violent conflict, to act as a deterrent for future generations. Additionally the approach of this project and relative ease of moving it from one location to another ensured that it could travel across the country and thereby reach and engage with a critical mass of people.

Picha Mtaani, Nairobi

.Art-Based Approaches the potential for conflict arises

In the run up to Kenya’s 2013 elections (held in March), newspapers reported fears of the repeated violence witnessed in 2007/8.[6] However, in many ways, this election was very different than the last. For example, there had been the adoption of a new constitution, as well as the associated reform of electoral bodies and the judiciary. Together this helped regain the confidence of the Kenyan people. Additionally in the run up to the elections there was also a huge peace narrative created by the government, NGOs, media and ordinary citizens which took a range of strategies that included the dissemination of peace messages through the medium of radio, television, music concerts, community forums, sport tournaments, text and social media messages.

Contributing to this peace narrative was the public art project ‘Kibera Walls for Peace’, that aimed to encourage peace and ease tension within communities and to celebrate diversity and promote unity. The project was an initiative of Nairobi centered community based organization Kibera Hamlets and American artist Joel Bergner. It took place in the informal settlement of Kibera. Beginning in January 2013, and lasting six weeks, the project created 7 murals at various locations around Kibera and painted a commuter train.

The narratives for each mural were the result of creative workshops which proactively engaged 30 young people. The workshops were themed around ‘peace keeping’, ‘violence prevention’ and the use of ‘public art for social change’. These themes were approached through activities involving games, discussions, drawing, painting, dance, performance and poetry. This proved to be engaging for young people to express themselves through creative means and to learn about something through the arts. The participants were aged 14-24. This was significant as many of this age group are out of school; as such they risk becoming idol and are vulnerable or at risk of violence.

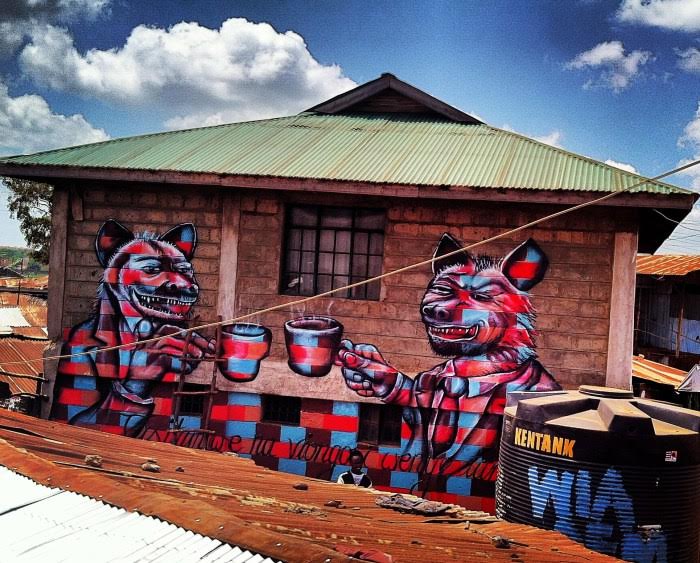

The Murals – through imagery and text – covered corruption, ‘tribalism’, living in peace and non-violence. Huge murals carried phrases in Kiswahili, which, translated to English, read ‘Peace is Forgiveness’, ‘My tribe is Kenya’ and ‘Youth we live for peace’. Other imagery focused on the youth’s role in previous bouts of violence and their role in society to engender positive change and peace; or imagery of hyena’s which represented politician’s self-serving ambitions.

Kibera Walls for Piece

Local graffiti artists (Bankslave, Swift 9 and Uhuru B) joined the project to paint a train and ten carriages – which runs through Kibera. The graffiti carried phrases, such as ‘down with tribalism, down with prejudice, up with peace’, as well as imagery of peace advocates, such as Wangari Maathai and Martin Luther King Jr. Bankslave, a graffiti artist from Kibera, felt graffiti was an important medium to use as it has the power to resonate and ‘speak’ with youth from Kibera and the rest of Nairobi.

Kibera Walls for Peace provided an opportunity, for young people and the community to experience forms of art that may rarely be afforded to them and as such it generated an element of excitement or intrigue, which helped spread the messages of the murals. These approaches contributed to generating public awareness, sympathy or consciousness to an array of issues chosen by the participants. Wat we can also draw from this project is how it provided a space for young people to become involved in community matters, to have a platform for their opinions and voices to be heard.

Summary

This short article has not acted as a criticism (of which a number can be made), though rather it has provided examples of how at different times and through different ways art can be used strategically in peacebuilding activities and offer alternatives to more formalized approaches. These examples highlight the possibilities that art, and the process of being engaged in artistic activities, can offer an awakening conscience and awareness of citizens in areas of peacebuilding and how they encompass civic reactions to violence and conflict through calling for reconciliation and coexistence. From these examples lessons can be learnt to inform future acts of bringing together the fields of art and peacebuilding. Given the complexities of peacebuilding and understanding that the peacebuilding field requires tools and approaches that are as varied as humanity, I would argue that while art-based approaches can only do so much, they are nevertheless a valid ally in peacebuilding.

[1] For example see: ‘In restless Kenya, 70% worry about another round of heavy bloodshed with presidential elections’, The Washington Times, May 11, 2017. ‘Kenya’s history of election violence may repeat itself’, The Star, April 29, 2017.

[2] See the post-election violence report by Waki Commission, commonly known as the “Waki report”

[3] See ‘Maasai Mbili Artists’ Collective’ – https://africanah.org/maasai-mbili-artists-collective/

[4] See ‘Nakuru police missed big picture in photo exhibition’, Standard, February 9, 2010

[5] See ‘Youths invade photo show’, Daily Nation, April 8, 2010

[6] For example see ‘Kenya’s largest slum fears repeat of 2007 election violence’, The Star, March 3, 2013