Surinam is a remarkable country. Although it is located at the north east coast of Latin America – Brazil is the neighboring country – it is seldom considered as part of that continent. Because it is close to the Caribbean islands you would assume that it is seen as part of the Caribbean. It’s not.

This remarkable, isolated position has a big influence on art in Surinam. On the kind of art, on the way it develops or does not develop, on art practice, on the identity of it, on the quality of it, on the way Surinamese art is positioned in the international art world and the art market.

Rob Perrée points out that Suriname is lost in the Caribbean.

SURINAME: LOST IN THE CARIBBEAN

I first went to Suriname six years ago. A number of Dutch-Surinamese artists had invited me to take part in the Wakaman project: an exchange project between Surinamese artists in Suriname and Surinamese artists in the Netherlands. The idea was for this exchange to result in a book and an exhibition in Fort Zeelandia, in the heart of Paramaribo, in the building where, in December 1982, army leader Bouterse – now President Bouterse – had had 15 opponents murdered.

I was supposed to contribute my thoughts, write a piece for the book and make a sort of report of the end results of the project. This would be mainly distributed via the internet.

Since I was not involved in the installation of the exhibition, this gave me some time to get to know the Suriname art world. Together with an expert colleague from Aruba I visited artists, collectors, banks, academies and local galleries. After a couple of days I asked our well-informed guide why I had actually only seen paintings and drawings. Her laughing response was to comment: “In Suriname art still hangs on the wall.”

This remark, and the cool nerve in programming an exhibition on a site that in my view was utterly tainted, not only gave me food for thought, but also greatly aroused my curiosity.

What sort of country is this? Why is there little development in art? What relationship does this country have with us, the former colonial rulers; with their neighbours, Brazil and the Caribbean; with the rest of the world? Why despite everything is it such a warm and friendly country; a country where we Dutch are still given a warm welcome; where a convicted criminal can be democratically elected as President; where “abroad” is often synonymous with the Netherlands.

I was to return often after that first visit. From conviction.

In order to form an initial concept I needed to gain a better understanding of the history of the country. What I had been taught in secondary school was biased, during my study of art history Suriname was simply never mentioned. It didn’t exist.

Suriname was a Dutch colony for more than 300 years. The English briefly interrupted us twice. Many tens of thousands of slaves were taken there during this period. They enabled the Netherlands to earn a great deal, particularly from the export of timber, cotton, sugar and coffee. The slaves were treated extremely badly. Suriname was notorious for this. Many, however, managed to escape the plantation. They hid in the interior from where the Dutch were unable to get them back. There they lived in small communities. Every now and again they even succeeded in going to free other fellow-sufferers from the plantations. In this way, the Maroons, without knowing it themselves of course, were writing history. In the end the Netherlands made the best of a bad job and in the second half of the eighteenth century they entered into a peace treaty with them. While it is true that the Haitian Revolution of 1804 made this country the first post-colonial independent black-led nation, it would still be fair to call the Surinamese guerrilla fighter Boni a forerunner of Toussaint Louverture. The Maroons’ valiant conduct has made them into a proud people. Later, this pride is to be severely challenged by various domestic events.

The Netherlands was one of the last countries to abolish slavery in 1863. At which time only 35,000 slaves remained. Contract labourers were brought in from India (these are the Hindus of today) and from Java (the Javanese of today) in order to keep the plantations running. Economically, it remains an uphill battle.

After a period in which the country was given a certain degree of self-government independence was finally gained in 1975. Some of the reason it took so long lay with the Netherlands, but the ruling Surinamese political parties also obstructed it for a long time. A schizophrenic situation to say the least. Dirk Kruijt describes the situation clearly:

‘From 1975 development aid, both the amount and how it would be spent, as well as the migration from Suriname would continue to define the relationship between the two countries. An official stance soon arouse concerning how the aid would be spent in which the tone was set by old grievances, suspicion, resentment and spite. The consolidating diaspora on both sides of the ocean became the source of an amicable relationship between mutually supportive family members, expressed in a constant stream of money transfers and perpetual transatlantic family visits. The odd relationship of amicable family links and a difficult relationship regarding aid define contacts between the two countries to this day.’ (Rozenberg Quarterly. The Magazine, June 2013)

For years on end the Netherlands continued to support the country from a sense of guilt. Suriname raked in the riches from the Netherlands under the motto: ‘it’s our money’.

For a long time money was also given without good foundation, without monitoring what was done with it, without investigating whether Suriname was able or prepared to spend the money well. As a Surinamese politician said: ‘We were used to getting money from the Netherlands on the basis of six sheets of A4.’

This changes in 1980 when the military seize power in the country. When they eliminate 15 opponents two years later all aid is stopped, under protest from the Surinamese government who refer to agreements made earlier.

On the resumption of these in 1988, the Netherlands starts to set increasingly strict requirements regarding how aid is spent. In Suriname this is seen as interference and colonial behaviour. Not without cause.

To sum up: for all sorts of reasons and for many years the Netherlands and Suriname have been holding each other hostage. Consequence: Suriname is sitting back waiting, not developing, not looking at other countries and the Netherlands retains its influence, both wanted and unwanted.

This situation is the most important cause of Suriname’s isolation. The official divorce of 1975 is effectively at the very most a legal separation.

The situation also ensures that a large number of Surinamese move to the Netherlands. There is a greater chance of success there. In 1975 when the Dutch government forces the population of Suriname to choose between a Surinamese and a Dutch passport, more than 40,000 Surinamese opt for the latter. There are consequently just as many Surinamese living in Suriname as in the Netherlands. Everyone has family in the other country. The two countries have been sentenced to each other. Not a good starting point for freeing yourself from isolation.

After all this time Suriname has not yet managed to build a stable economy. The political system is not infrequently contaminated by corruption, drug trafficking and all kinds of other dubious activities so that internationally Suriname is not perceived as a sound (trading) partner. A senseless and yet still violent civil war in the nineties confirmed the country’s negative image. While NGOs and other international organisations are almost pouncing on many other newly independent countries, Suriname gets almost none of this sort of attention.

Shrewd foreigners and foreign companies prospect for many mineral resources, including gold and bauxite. Bauxite concessions are sold to the Americans (Alcoa), illegal Brazilians take the gold away, and the Chinese have control of a large share of the food market. In exchange for ‘pocket money’ politicians enter into contracts that do not benefit the country. To put it mildly.

The weak economy and the draining away of so much money mean that the country’s infrastructure remains poor. There are no funds for laying good roads. The only train connection – to the airport – is out of order for years. Direct flights to other countries are still extremely limited. And therefore expensive. Licences are difficult to issue because countries such as the USA have doubts about air safety. Suriname is simply difficult to get to; the Surinamers in turn find it hard to fly out. Tourism is struggling to get off the ground.

For a substantial part education is based on obsolete Dutch teaching methods so that existing talent, and there is more than enough of it, is either not properly cultivated or feels forced to seek its fortune abroad. Incompetence and a lack of knowledge also prevail in many professions, since most of the educated Surinamese do not return to their country.

The Netherlands may have put, I prefer not to say invested, a lot of money into the country, however research shows that the amount for cultural projects has always

remained low, meaning that the country has never been able to compete in this field internationally. As a high-up Surinamese official put it: “Calvinists settled this country. They never had much time for culture.”

For a long time Suriname has had no or hardly any engagement with its neighbours: Latin America and the Caribbean. These neighbours in turn do not consider Suriname to be part of their region. Of course you can view ‘the Caribbean’ as an ideological construction, an imaginary area, as a colonial concoction, as a tourism-oriented fabrication dreamed up by advertising agencies, as a Garden of Eden. There are, naturally, huge differences between the various countries that are part of it – language, religion, population composition – but there are also many similarities, not least of which is a shared past. “The unifying factor of the diversity characterizing the Caribbean is rooted into a common history’ (Graciela Chailloux, University of Havana). (2) All the same, Suriname has shown very little interest in this over the years. Until recently no specific action has been taken to look for or make a connection. Natural ties prove to be less strong than the ties defined by colonialism. By the way, Google Maps does not consider Suriname to be in the Caribbean!

What does this mean for art in Suriname?

When a country is isolated, art does not get the chance to measure itself against others and thus to develop either. The run-down conditions in the country itself have an additional effect on this isolation.

There are currently two art academies. The Academy for Arts and Cultural Education was founded in 1981. It is set up according to a traditional Dutch model. International developments pass it by. A couple of years ago the principal was still saying he wanted nothing to do with installations. They were not art. The Nola Hatterman Art Academy came along in 1984. The set up here is completely different. Here, pupils and students of in principle all ages are offered the chance to develop their artistic talent. This often takes place in the traditional way, however this academy has made an attempt to join in with less traditional approaches via an exchange project with the Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. This attempt has certainly had success for a handful of artists. Due to the inequality of the exchange – more Dutch artists went to Suriname than Surinamese artists managed to get to the Netherlands – the overall effect remains minimal.

This lack of good, modern education has resulted in a situation where the older artists have generally been educated in the Netherlands, where a section of the generation now in their forties went to Jamaica and have now returned with new insights and different work, and where almost all of today’s artists have or have had something to do with Nola Hatterman in one way or another: temporarily as a student, as a teacher or as a manager. Ultimately neither institute has been able to advance the development of the visual arts in Suriname to any significant degree.

Suriname still has only one gallery. Almost every artist has links to it or is represented by it. This gallery is energetic, stimulates all sorts of activities, invests in its artists, will move to new, much better premises, but has no connection to the international circuit. It furthermore serves a market that is far too small and is not wealthy enough. Out of sheer necessity prices for art are therefore low and incomes bear no relationship to the time and energy put in.

Because there is no real market for art – though there is plenty of interest in art, openings are well attended – the majority of artists cannot support themselves by their work. They have to takes additional jobs in order to survive. Not a problem exclusive to Suriname, but added to all the others, certainly a substantial problem. There are no state subsidies. Subsidy funds still come from the Netherlands or out of the ever-decreasing budget of the Dutch Embassy in Paramaribo. Banks sometimes step in to support the realization of a project, but in general there is no infinite pool of sponsors.

There is no museum of contemporary art. The Surinaams Museum is a history museum rather than a museum for the visual arts. The artist Marcel Pinas has set up the Contemporary Art Museum Moengo (CAMM) on the edge of the interior. A bold plan, but at present this is still just a large, dusty hall where his own works are hung/placed. As yet there are no resources to take this to the next level. The intention is to exhibit regional work and work by the artists in residence.

At present therefore the interested Surinamese and the academy students have no opportunity to get to know the art of the regions, let alone international art. Despite being a very valuable source of information the internet is not a viable alternative, nor is the fall back position of a well-stocked library, since this does not exist.

Artists cannot measure their work alongside that of international colleagues, neither is there any yardstick for their work at a national level. There is a lack of art criticism. Courses do not provide a programme specialized in this, experts who might be able to do it, baulk at the thought because after a harsh criticism, however justified, they will have to return to a community that is so small almost everybody knows each other.

Does this bleak story imply that Suriname is lost to art?

I will not go so far. There have been recent developments, however fragile they may be, that offer hope.

Something has changed politically. While President Bouterse may have a dubious past, his government is ensuring that the younger generation in particular can be proud of its country. Under his rule the customary yearning for the Netherlands has more or less disappeared. He is also trying to prevent the income from mineral resources from leaving the country. For instance he has reached agreements with Brazil to curb illegal gold digging by Brazilians. In addition he appears on the international stage as often as possible. He attends international conferences and has close ties with Cuba, Venezuela and, it is said, South Africa. He seems to be throwing open the windows and broadening the view.

In the late nineties a number of artists went to the Edna Manley College on Jamaica for a follow-up study rather than to a Dutch academy. When they returned their attitude had changed. In the words of Marcel Pinas: “On Jamaica we had to do something with the feelings that were inside us, we had to look for our own subject matter and for the means of expression that suited this best.” Art did not have to hang on the wall.

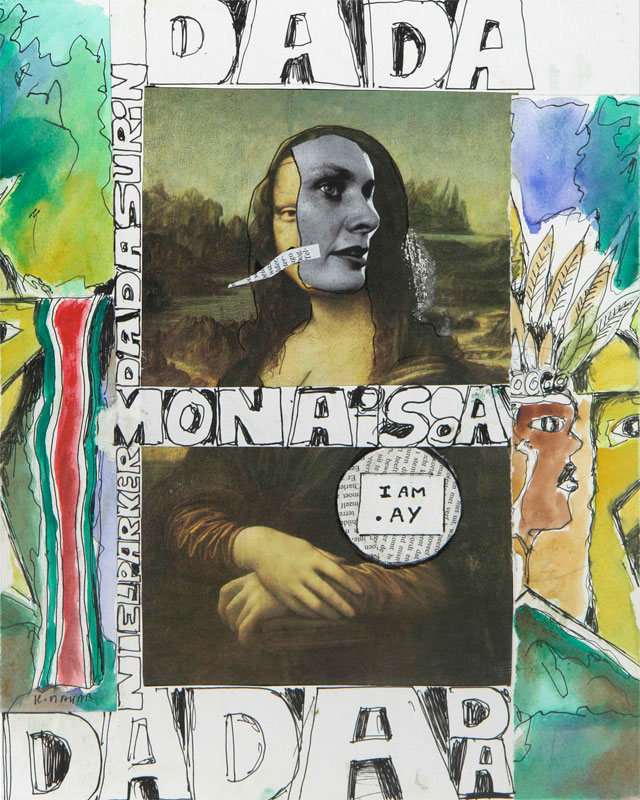

Kurt Nahar, one of the many collages he made.

Kurt Nahar, one of the many collages he made.

In 2010 this altered mentality was able to further take shape in the Paramaribo SPAN project, an exchange between Rotterdam artists and artists from Suriname. An exhibition, a book and a fringe programme. Co-curator Christopher Cozier from Trinidad in particular succeeded drawing the Surinamese artists out of their comfort zone. He pushed them to work from a personal concept and not to allow themselves to be hampered in their means of expression. The closing exhibition provided some surprising results.

George Struikelblok, I Wish, I Hope, I Think, I Want, 2010.

George Struikelblok, I Wish, I Hope, I Think, I Want, 2010.

Meanwhile Marcel Pinas is busy realizing his greatest installation: the Moengo project. He has set up the Tembe Art Studio in his native district. Here the creativity of young Maroons is addressed in all sorts of ways and on every level by guest teachers. He is initiating an artist in residency for which international artists are invited to develop a project that must result in a sculpture or installation for the Moengo Sculpture Park.

The local population must be involved in the process as much as possible. Pinas is adding more to his museum, adding guest rooms, a restaurant and an annual big event in the field of music, theatre or art in order to attract a larger audience to the interior and to have them learn about the culture there. Moengo is no longer an isolated town: the Chinese and the Dutch have provided excellent links. Pinas has placed himself on the international map with his Moengo project. He is the stimulating force for Surinamese art. He is an inspiration, especially for young artists.

A few years ago an exhibition hall opened in Paramaribo – appropriately called De Hal or The Hall. Again an initiative by Readytex, the only gallery. The hall makes larger presentations possible and caters for the growing interest in and demand for art. A location such as the hall is incredibly important for a country where the infrastructure leaves much to be desired.

There is currently a group of young artists – Miko Veldkamp, Ruben Cabenda, Xavier Robles Medina and Harvey Lisse for example – that refuses to be held back by Suriname’s eventful history, that realises that they will not be automatically granted subsidies and that, due to the internet, are not only much more closely in touch with international developments, but also have the ambition to join in as much as possible. They are not waiting to see what happens, they are taking the initiative and going for it. An attitude that has taken a long time to come.

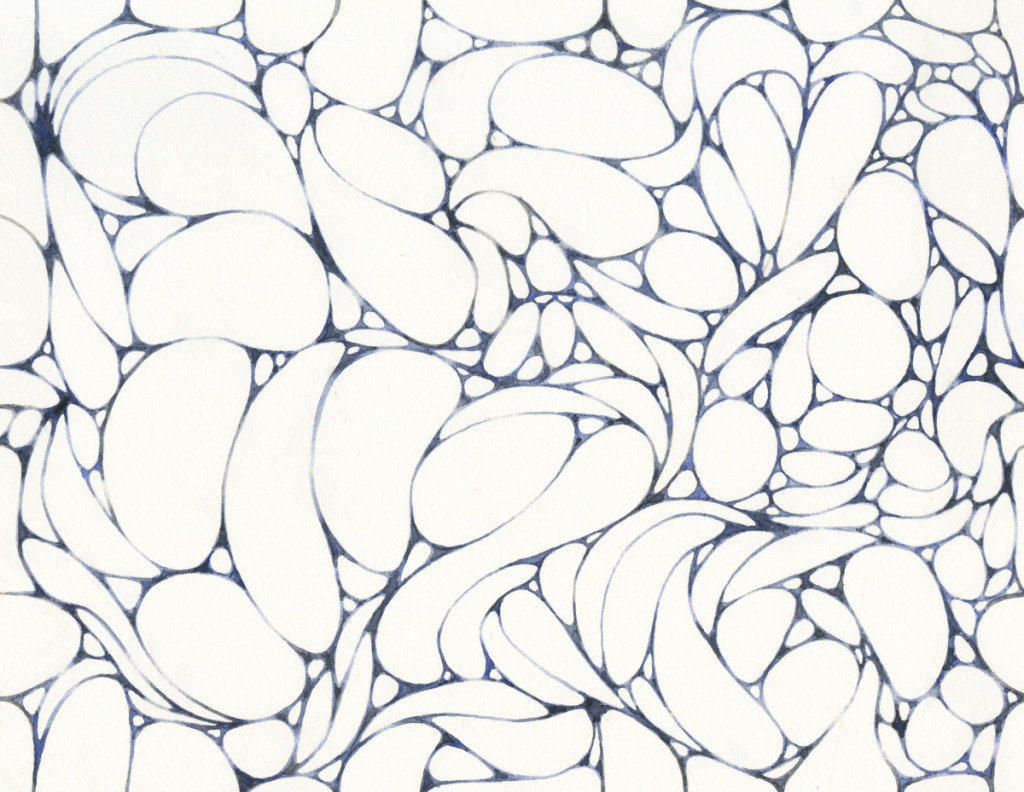

Ruben Cabenda, Untitled, 2014.

Ruben Cabenda, Untitled, 2014.

Xavier Robles Medina, Bathers, 2012.

Xavier Robles Medina, Bathers, 2012.

Harvey Lisse, Freedom and Slavery, 2012.

Harvey Lisse, Freedom and Slavery, 2012.

Nevertheless, all these positive developments are still extremely fragile and depend too much on the enthusiasm and the efforts of just a few people. Structurally, not enough has yet changed.

I do not know what the definitive solution is; Suriname must come up with this itself.

I can, however, offer a few suggestions:

The education should respond better to developments outside Suriname. The Nola Hatterman Art Academy has recently acquired Marcel Pinas as director. He should be able to make a start on this.

More galleries would be helpful, because in that way access to the international circuit has more chance.

It helps when the artists act more as a group and formulate a strategy. For instance they could initiate and organize more exchange projects with Caribbean countries and with Brazil.

The government and business community should invest more in art and culture. They hardly seem to be aware of the fact that art and culture can stimulate tourism.

The University of Paramaribo should create a course in art history. This would develop the expertise that would enable art criticism for example and use could be made of this in the museums, galleries, etc.

Suriname is a country with huge potential and a rich culture. It is a terrible shame that it’s development is progressing so slowly and that the rest of the world does not have the chance to learn more about it.

Amsterdam/Brooklyn, June 2014.

Copyright: Rob Perrée.

(This text was lectured at the international conference ‘Contemporary Caribbean Visual Culture. Artistic Visions of Global Citizenship’ at the University of Birmingham, UK. June 2014.)

Bio: Rob Perrée is art historian, independent writer and curator. He published many articles and books on contemporary art and he is the founder and editor of Africanah.org. He lives and works in Amsterdam and Brooklyn.