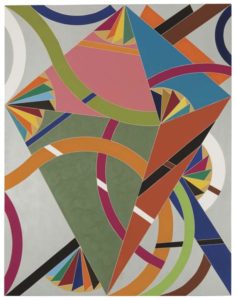

William T. Williams at the Frieze, New York, May 2-5, 2019

Mercer’s Stop, 1971

About:

“One of the things I remember most is … people asking me … ‘Why are you making abstraction? It’s not African American art.’ And I would always say, “Well … you tell me what it should look like. Jazz is the most abstract of all music. Music is totally abstract. How can you not say there’s a tradition of abstraction?’ I would talk about quilts, point out that the geometry of quilts is certainly coming out of abstraction. There is this rich tradition; all you have to do is see it and to use it.”

*

The work of William T. Williams ranges in style from his early geometric abstractions, to almost-monochromatic explorations of texture, to an abstraction that derives its force from productive tension among colors and forms. While he has consistently tested the limits of his earlier styles and developed new approaches, his meticulous attention to the process of art making has remained constant. A master of brushwork and color, Williams creates his paintings in series, working through a labor-intensive process that often includes drawings, watercolors, and prints.

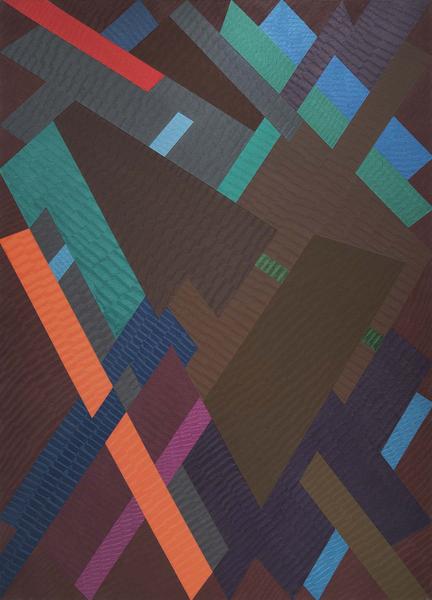

Texas Lady, 1973

From the outset of his career, Williams’ art was characterized by bold color and daring compositions that paid homage to and challenged the abstraction that had come before it. He emerged at a time when abstract expressionism was in decline, while pop art, color field painting, and minimalism were on the rise. Concurrent with this aesthetic transition were social and political transformations that saw artists, intellectuals, and activists challenging the exclusionary practices of New York’s white- and male-dominated art institutions. These critiques came in multiple forms, including an approach to art that favored figural representation embedded in a politics of struggle and an assertion of identities misrepresented by or excluded from American culture. Such images were a necessary correction to a history of omission and caricature, but they risked being received by the art establishment in a way that affirmed its tendency to ignore work by abstract artists who were also African American.

*

Living in an artist loft building on Broadway that over the years included neighbors Kenneth Noland, Joel Shapiro, Janet Fish, and William Copley, Williams believed that abstraction offered him greater creative and expressive freedom than figural representation, but he was also wary of the potential cold, impersonal aspect of painting that was merely about painting. Williams thus developed an approach that rendered the abstract representational, not only through titles replete with autobiographical references, but also in the shapes he incorporates. These shapes resonate with cultural history and personal memories of a childhood spent in the northern, urban environments of New York as well as the southern landscapes of rural North Carolina. Jazz, too, became an important site of convergence where memory, history, and a black American abstract tradition met. Finally, quilting was for Williams another manifestation of an African American tradition of abstraction. His artwork often incorporates the diamond shape as a visual motif that functioned “as a stabilizing force, a form that interacts compositionally with what’s around it. But it goes back to the quilts of my childhood, the patterns and forms I grew up with.”

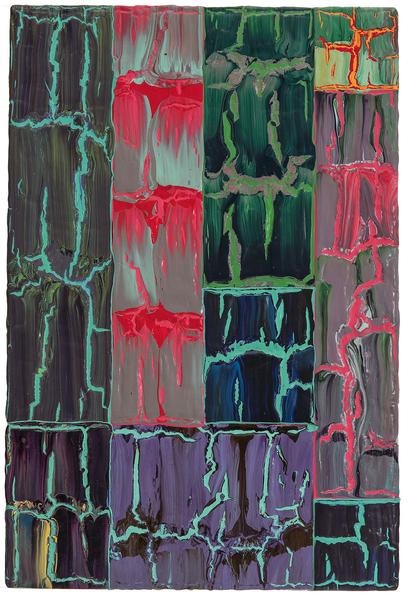

Quick Step, 2000

The synthesis between personal/cultural narrative and abstraction that Williams developed early on in his career was met with deserved success. Born in rural North Carolina, Williams moved to New York with his family as a youth. He attended the School of Industrial Art (now the High School of Art and Design), before enrolling at Pratt Institute in 1962. At Pratt, he studied with some of the foremost figurative painters of the day including Richard Lindner, Philip Pearlstein and Alex Katz, but it was painter Richard Bove who encouraged Williams to work from intuition and memory rather than from observation. The resulting abstract work found support amongst his professors whose encouragement led Williams to pursue graduate studies at Yale University. The graduate department at Yale provided a rigorous theoretical foundation and studio practice for the artist as the faculty included George Wardlaw, with whom Williams studied during his first year, Jack Tworkov, Al Held, Lester Johnson, and others. Held played a particularly encouraging and influential role for Williams. “[It was the] best experience I ever had. [Held] was relentless in terms of pushing me….it was really good for me because it forced me to focus on what I wanted to do and why I was doing it.”

*

Williams completed his MFA at Yale in 1968 and in 1969, now living in New York, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) purchased his Elbert Jackson, L.A.M.F. Part II (1969). That same year, he was included in the Whitney Biennial and he organized X to the Fourth Power at the newly opened Studio Museum in Harlem. A Smokehouse muralist from 1968 to 1970, Williams was instrumental in establishing the artist-in-residence program at The Studio Museum, which remains to this day a core mission objective. In 1971, Reese Palley Gallery, New York mounted Williams’ first solo exhibition and he began teaching at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York (CUNY), where he was on faculty for four decades, inspiring hundreds of students including Nari Ward and Arthur Simms. In 1965, he spent a summer in Maine as a student at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, returning as faculty in 1971, 1974, 1978, and 1979; the latter year he served as pro tem Director. In 1975, Bob Blackburn invited Williams to make a print at the Printmaking Workshop; over the next 22 years, Williams collaborated with Blackburn to produce 19 editions, as well as a number of unique print projects. In 1977, he participated in the Second World Festival of Black Art and African Culture, held in Lagos, Nigeria, which marked his first time in Africa. The trip, especially the movements of patterned clothing he saw on the street, had a profound effect on his art, and Williams began a series of paintings inspired by this African tradition of abstraction.

Let Me Know, 2017

Williams has continued to revise, adapt, and transform his style, and this dynamism combined with a consistent set of formal and thematic concerns has contributed to the longevity of his luminous career. Beginning in 2016, Williams now spends most of his time living and working in the Connecticut countryside, after decades of working in SoHo, where he has converted an old barn into a soaring studio flooded with natural light. This new environment, immersed in nature, has had a profound, albeit subtle, effect on Williams’ recent work, whose encrusted abstractions in richly-colored palettes reflect the shifting dynamics of seasonal and atmospheric change.

*

Williams has been the recipient of numerous awards and fellowships, including: the Individual Artist Award in Painting from the National Endowment for the Arts (1970), a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship (1986), The Studio Museum in Harlem Artist’s Award (1992), a National Endowment for the Arts Regional Fellowship (1994), a Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant (1996), the Brandywine Workshop’s James Van Der Zee Award for lifetime achievement in the arts (2005), the North Carolina Governors Award for the Fine Arts (2006), the Alain Locke International Award from the Detroit Institute of Arts (2011), and the Skowhegan Governors Award for Outstanding Service to Artists from the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture (2017). Recently, Williams was inducted into the newest class of National Academician members at the National Academy Museum & School in New York (2017) and he is the recipient of the 2018 Pratt Institute Legends Award and the 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award at the 30th Annual James A. Porter Colloquium, Howard University, Washington, DC. The Cumberland County native is also the first African American contemporary artist to have his work (Batman, 1979) included in the widely-used reference work The History of Art by H.W. Janson.

*

For over forty years, Williams’ work has consistently been shown at home and abroad. Representation in groundbreaking exhibitions includes, To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (Addison Gallery of American Art, 1999); What is Painting? (MoMA, 2007); Blues for Smoke (Museum of Contemporary Art, LA, 2012) and Witness: Art and Civil Rights in The Sixties (Brooklyn Museum, 2014). In 2016, he was featured in the inaugural exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American Art and Culture (Washington, DC) and in 2017, his contributions as part of the mural collective Smokehouse Associates were examined in Smokehouse, 1968-1970 at the The Studio Museum in Harlem. His work is included in the exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, recently at the Tate Modern, London, England, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR, and Brooklyn Museum and now on view at The Broad, Los Angeles, CA. For this exhibition, as part of its ongoing series of artist documentaries, the Tate Modern produced a short documentary film about the artist, providing a rare and intimate glimpse into his world.

*

Recent solo presentations of the artist’s work include William T. Williams: Theme and Variations at the Morris R. Williams Center for the Arts, Lafayette College in Easton, PA (2009) and William T. Williams: Variations on Themes at The David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora, University of Maryland in College Park (2010). In 2017, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery presented its first solo exhibition for Williams, celebrating five decades of work and featuring an overview of the artist’s most major painting series. The exhibition was accompanied by a fully-illustrated catalogue with engaging conversations between the artist and Thelma Golden, Director and Chief Curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem, and Courtney J. Martin, Deputy Director and Chief Curator at Dia Art Foundation. The gallery will present a second solo show, featuring a new body of work, in September/October 2019.

Williams is represented in over thirty public collections, including the Detroit Institute of the Art (MI); Fogg Museum (Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA); The Menil Collection (Houston, TX); Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY); Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Collection (Albany, NY); North Carolina Museum of Art (Raleigh); Philadelphia Museum of Art (PA); Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska (Lincoln); The Studio Museum in Harlem (New York, NY); Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, NY); and Yale University Art Gallery, Yale University (New Haven, CT).

Williams lives and works between New York City and Connecticut. Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC is the exclusive representative of William T. Williams.