“We could not refer to our role in art history, because we did not play a role in that history.” One of the many remarkable quotes out of an exclusive interview with the African American artist Kerry James Marshall. “Markets are not driven by black people. The way artworks travel around the world has a lot to do with how the market functions”, is another.

An interview with Kerry James Marshall

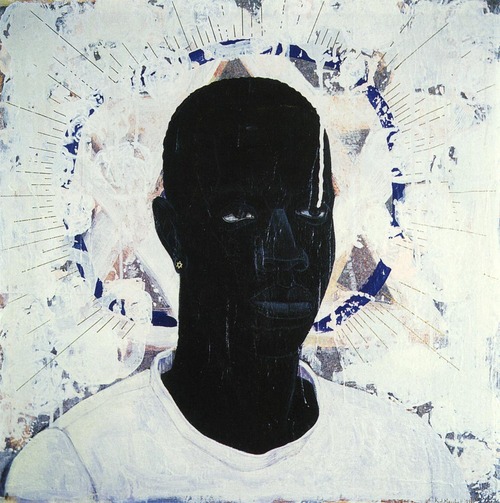

I CALL ATTENTION TO THE ABSENCE OF THE BLACK PRESENCE

Kerry James Marshall (1955) grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, and in the housing projects of the Watts section of Los Angeles. Birmingham at that time was one of the central stages on which the Civil Rights movement played out. Martin Luther King called it “America’s worst city for racism”. It was a klu klux klan stronghold, and it was the site of the infamous 1968 church bombing that killed 4 black school girls. Two years after this heinous act, the family had moved to Los Angeles. Their arrival coincided with the Watts race riots, where 34 people were killed, more than 1,000 wounded, and more than 3,000 were arrested. The memory of these events has had a profound effect on the artist. He feels that “It shaped the person that I have become.” He studied at Otis College of Art and Design in LA. He was one of four black students. His career started at the end of the seventies. One of his major influences was the novel ‘Invisible Man’ by Ralph Ellison. In the introduction of his book he talks about the notion of being and not-being, of presence and absence. Reading the book Marshall became aware of his ‘mission’. Ellison had verbalized his slumbering theme. He painted his first “cold black” silhouette against a black background: ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his former Self’. . After his participation in the Documenta of 1997 his work gained more attention. In the USA he is considered now one of the most important African American artists. In Europe he is not well known. His exhibition in the M HKA in Antwerp – ‘Painting and Other Stuff’- was the first big overview of his work in Europe.

It’s there, in one of the bright white rooms of the museum, that I had an interview with him.

RP You call yourself a history painter. What do you mean by that?

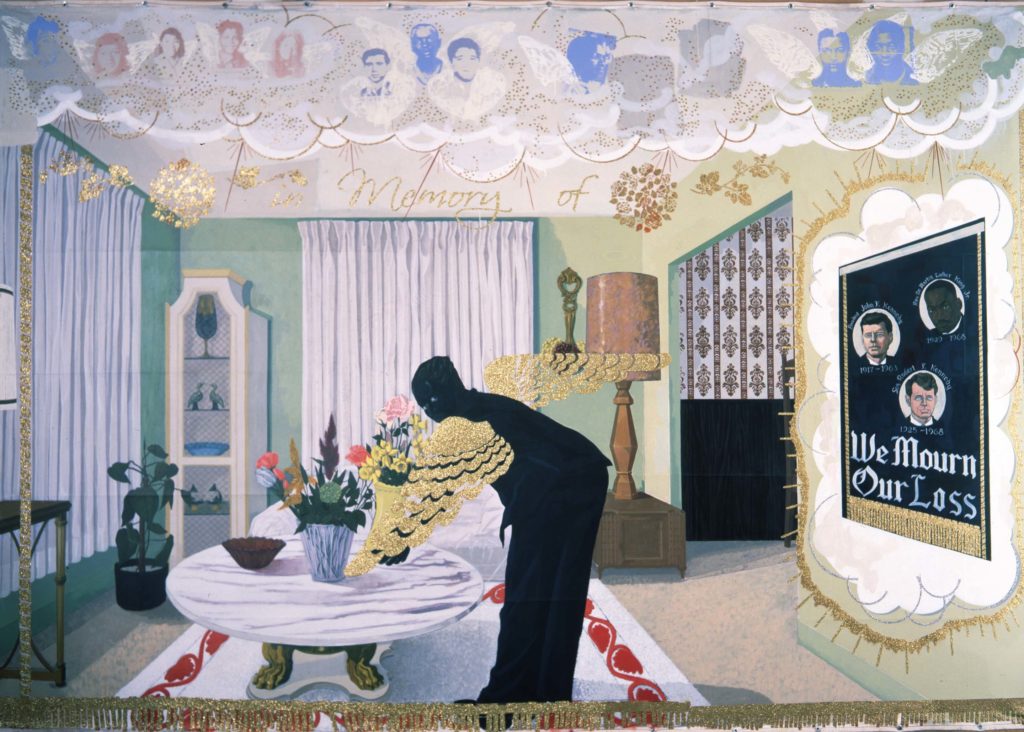

KJM I walked around in many museums where they show art from the past, like the Metropolitan and the Louvre… These big scale paintings with authority, painted with technical virtuosity. They claim respect. I never saw that kind of paintings with black figures. In my work I try to get into a dialogue with these kinds of paintings. It is not my aim to illustrate history; I don’t have a journalistic approach. I occupy myself with the consequences of history. I don’t want to show action or drama. My works are more about the remembrance of activities. My ‘Souvenir’ series is exemplary for my philosophy about history. In these paintings I include portraits of people like Martin Luther King and the Kennedy’s who played a key role in the sixties, the Civil Rights era. I don’t show what they did; I just try to bring memories alive. Because of the scale of the paintings I more or less force the viewer to deal with it.

Souvenir I, 1997

RP Is there a difference for you, because of the history aspect of your work, between showing in the National Gallery in Washington and showing in the M HKA in Antwerp?

KJM Both venues are important markers of recognition. Showing there is a signal to the viewer that it is worth going to see my work. Some ideas or issues resonate perhaps more in the US than here. But even that is not completely true. People generally have a very shallow understanding of history, even at home. Since my approach is sort of indirect, it is not always clear what it is supposed to be about. Black figures are always present at the center of the narrative. They claim a lot of attention. Perhaps that aspect works better for the US than for Europe. Could be.

RP Another reason why I ask that question is that I am still wondering why your work is hardly known in Europe.

KJM It’s not because my work is too American. If anything it’s more pan-African in terms of its sensibility. There are more basic factors. Markets are not driven by black people. The way artworks travel around the world has a lot to do with how the market functions. Since China is an economic power Chinese art gets a lot of attention. Collectors tend to follow the market. My work is not bought by European collectors. To illustrate my point with another example, if Luc Tuymans makes positive remarks about my work it means a lot. It makes a difference. If I show my admiration or respect for his work it means nothing. He is connected to a powerful European market, I am not.

RP At first you made abstract paintings. When you started to paint figurative, at the end of the seventies, it was in fact not done.

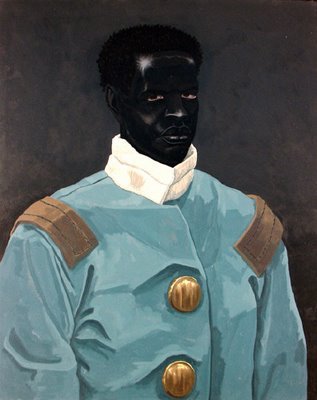

Believed to be a portrait of David Walker, 2009

KJM I found out that it is impossible to make art for the sake of art, art that speaks to itself only or conceptual art when you grow up in an environment like mine. The Civil Rights Movement, the murder of King, of the Kennedy’s, of Malcolm X, the racial riots, the violence of the Black Panters. Besides that, it was important for me to represent black people. We were not represented at all. We were almost absent in the museums. Betye Saar, Charles White, David Hammons, that was about it. We did not have masters like Van Eyck. We were marginalized. We could not refer to our role in art history, because we did not play a role in that history. I felt it as my responsibility to fill the gap, so to say.

RP Wasn’t there a change in the nineties?

KJM The only reason why a group of black artists found their way in was because identity was a subject in their work. Identity was a popular theme in the nineties. We were never perceived to be innovators. There were black artists who made abstract work in the fifties and the sixties. Identity was no issue in their paintings. But they came in even after the second generation of Abstract Expressionists. So they did not have a status. They did not make history. This is the reality I am talking about. Power is the real issue. The black body in the Western world is a weak body. Economically, politically and psychologically. We lack the capacity to shape the world around our interest. We are not in charge. I am only in charge of my capacity to make a thing. The market is not in our control. The number of black people who can buy art is very small. There is no critical community of black people who understand what the implications of these works are. We are not participating in the definition of art works. You talk about a new generation of black academics who are driven to find their way into the discourse. True, they are there, but how influential are they? It is a small group. When do they show up in Flash Art or Frieze? When do their ideas meet the marketplace? I don’t say there is a deliberate attempt to marginalize us, but there is a whole tradition in the Western world that was setting the rules. There was a moment in that history when other cultures were involved, appropriated – in the work of Picasso for instance – but that was more about interest in their artifacts as raw material, as a way to transform part of that tradition. Where do we fit in? What does it mean when we come in? You can deal with it as inevitability but you also can challenge it. That is what I do. I call attention to the absence of black presence.

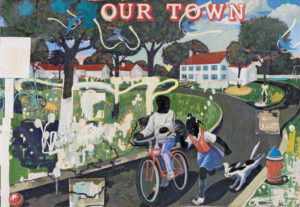

Lost Boy AKA Black Johnny, 1993

RP In what way?

KJM Perhaps I am political, but I don’t want to be moralistic in my work. A painting cannot change things, it shows things, that’s all. My ‘Who is afraid of Red, Black and Green’ is a good example. The viewer will immediately refer to the famous work of Barnett Newman, but because of the ‘strange’ colors, he also has to think of something else. The painting does not refuse the role of the original as a painting, it accepts its role as a painting, but because of the colors of the pan-African flag of Marcus Garvey, it gives in an indirect way visibility to black people. I put black figures in the center of my paintings because white figures that represent the ideal beauty and the ideal humanity are all over art history. In a way I imitate the ‘masters’. I make big works referring to all kind of styles and genres that were used in the history of painting in order to clear my way to the museum. What they can, I can do too. Their representation of white people is no less than my representation of black people. If the Prado is going to collect contemporary art I want my work to be part of that collection.

RP You had the artist Charles White as a teacher. What role did he play?

KJM It was not so much about White as a teacher. It made me happy to experience that he was there, alive. And to look at the work he made. That stimulated me. I wanted to be where he was. He made the most powerful images of black people I have ever seen. I wanted to be as powerful as he was.

In the evening there was a talk between the Belgian painter Luc Tuymans and Kerry James Marshall. They have been friends for many years. Marshall lives in Chicago, and they met when Tuymans had a show there. Tuymans praised the work of his colleague with adjectives like “radical”, “perfectionistic”, “deliberate”, “specific” and “with elements of sublime dignity”. Marshall was just smiling, which is remarkable for a talkative man. He must have realized that his exhibition in the M HKA was the best response to these compliments.

Rob Perrée

Brief biography

Rob Perrée is art historian, writer and curator. He is editor in chief of Africanah.org. For additonal information: www.robperree.com.

Credits:

All the works of Marshall: courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.