“His work is of significance to the history of art not simply within the context of the artist’s particular geographical and historical location. His work (and its history) opens up questions about experimental art practices; and the dialogues that take place between generations of artists (working across geography and historical time).”

Yvette Greslé on Issa Samb.

Issa Samb: From the Ethics of Acting to the Empire Without Signs

It is the opening night of Issa Samb’s solo exhibition ‘From the Ethics of Acting to the Empire without Signs’ (Iniva, London). Amongst a room of objects, films, installations, paintings and collages Samb stands still and silent. Through Iniva’s enormous, street-facing window I watch as people walk past or peer inside. The artist holds a gold helmet (reminiscent of Ancient Civilisations) and a cape made up of cloths of various textures and designs. The objects are dropped to the floor: deliberately discarded. Samb begins to make sounds and perform gestures. He beats his chest and the sounds, their rhythm and scale, shift and transform. Silence and then noise: sounds that escape language with its alphabets, and words. I am drawn into an affective and bodily space outside of formal, official language and speech. Samb begins to walk and stride; and gesture and demonstrate with his arms. Gestures are increasingly exaggerated and forceful. I laugh at the performed absurdity as he gesticulates at mixed-media works (paintings and collages) on a wall. As the performance ends, and he leaves, he interacts directly with members of the audience: what transmits between them in this ephemeral moment remains unknowable. The discarded helmet suggests civilisations that rise and fall across historical time. The signification of the cape is less legible: its fabric is printed with patterns of flowers. History, Absurdity and Myth come together in this performance amongst people and objects.

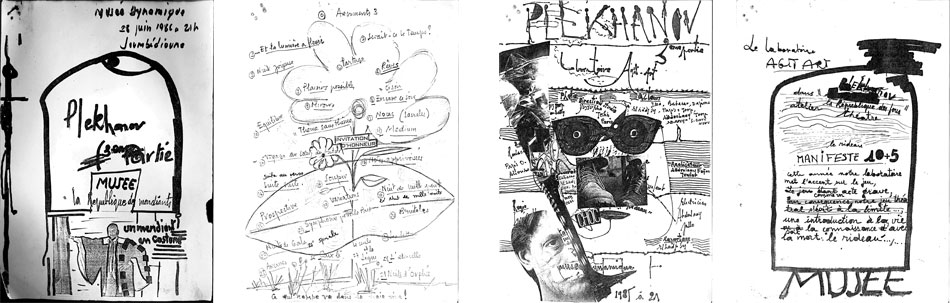

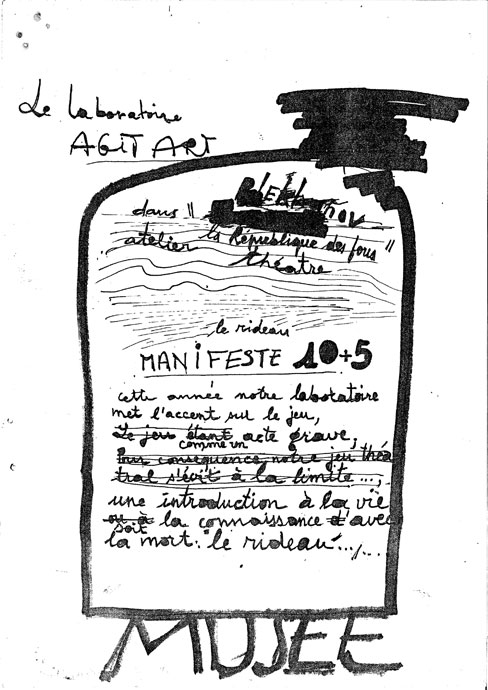

Issa Samb (born in Dakar, Sengal, 1945) is an artist of great historical importance: a retrospective of his work appeared at the National Art Gallery (Dakar) in 2010. His work is of significance to the history of art not simply within the context of the artist’s particular geographical and historical location. His work (and its history) opens up questions about experimental art practices; and the dialogues that take place between generations of artists (working across geography and historical time). In 1974, Samb founded (together with a group of artists, writers, filmmakers, performance artists and musicians) the Laboratoire Agit’Art. The group included the filmmaker Djibril Diop and playwright Youssoufa Dione (both deceased); and the painter El Hadj Sy. The Laboratoire emphasised ideas of process, experimentation and agitation. Staging institutional critiques (and narratives that resist the idea of art as commodity) the group foregrounded impermanence and the ephemeral. The title of the exhibition at Iniva, ‘From the Ethics of Acting to the Empire without Signs’, is a reference to an Agit’Art manifesto on acting produced by Samb and Dione. The show includes an archival display of material that speaks to Samb’s engagement with Laboratoire Agit’Art and Senegalese art and politics. Central to Samb’s practice is his work with other creative practitioners: Events accompanying the exhibition include a talk on African Art Collectives with Elvira Dyangani Ose (Curator International Art, Tate Modern) and the art historian TJ Demos (University College London). Samb’s work was previously shown in London in 1995 at the Whitechapel Gallery: this exhibition was titled Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa. He lives in Dakar where his ‘courtyard-home-studio’ is a permanent exhibition space of objects which continuously change and transform. In the spirit of this living-work environment the exhibition at Iniva stages materials and works shipped from Senegal together with found elements collected in London’s street markets.

In a conversation with Koyo Kouoh (who curated ‘From the Ethics Of Acting …’) I ask her about Samb’s relationship to his practice and work to date: ‘I think Issa’s work is really about the transmission of energies and ideas. It is not about building a career or developing an oeuvre. His main drive is the relationship, the connection that can be established with other people’. [1] This sense of the artist’s relation to others is suggested throughout the show, and appears in almost indiscernible ways in the curation itself. I notice it in the decision to leave the windows to the street outside unobscured so that viewers can look out and passers-by can see in. The exhibition’s installations of images, objects and sounds suggest human presences: experienced as poetic-affective sensations these are situated in vision and listening. As I enter the main exhibition space I pause at an untitled installation (2014) of ephemeral, everyday things such as worn handwritten notes, annotated drawings and x-rays suspended, with clothes pegs, on string. My line of sight extends through the transient, translucent matter of the x-rays (with their phantom imaging of skeletal structures) and out through the windows and onto the street. The passage of time, journeys (literal and metaphysical); and human rites of passage (life, birth and death) are invoked in works such as ‘Corps’ (2013): earth is wrapped in cloth which takes a shrouded human form. Wooden crosses bound in red cloth rest on top of this uncanny object of wrapped earth. Adjacent to ‘Corps’ is a worn, old-fashioned suitcase: I imagine theatre props and symbolic significations. The suitcase performs (as I perform a private visual game) themes of travel, migration, exile but also, in a spatial relationship to ‘Corps’, the metaphysical journey of death.

Installation view, Iniva, Rivington Place, London, 2014.

Installation view, Iniva, Rivington Place, London, 2014.

The exhibition includes a number of films by Jean Michel Bruyère (in which Samb performs). Kouoh comments: ‘The presence of Jean Michel Bruyère is important in the exhibition. Issa has different circles of exchange. Artistically Jean Michel is one of these, and has been important for many years. But it’s the very first time that a very small selection of work, that they have done together, is presented outside of the context of Jean-Michel’s own production. It is presented rather in the context of Issa Samb’s production, and within the context of a show about him’. [2] The films draw (similarly to the objects) on themes that suggest elemental human experiences, mythological in their signification and force. In one of these (screened upstairs) men group around a pirogue at the edge of an ocean. Their figures are blurred and there is no sound. There is the disturbance of sudden, unexpected noise as they kick the sides of the boat. The camera focuses in on its interior where Samb lies in a position reminiscent of Ancient burials. The pirogue is dragged into the sea and disappears. The idea of place, and of landscape, is threaded through the exhibition. In films by Bruyère, the symbolic capacities of landscape and the natural world appears central. In cultural texts and spiritual thought landscape is a site symbolically linked to self-exile, migration, and the exploration of an inner life detached from material and social worlds. In the films, formal devices deployed include blurring and the obfuscation of features and figures. In one of these, Samb strides through a natural, unpeopled landscape. Themes to do with landscapes and travel appear too in the object-based installations: ‘Skull’ is the skull of an Ox, a prop from Mambéty’s 1973 film Touki Bouki, the classic Senegalese road movie about the connection to home. The prop, appropriated from a film by the artist’s Laboratoire Agit’Art collaborator, takes on a poignant meaning in the context of the exhibition and is presented, uncharacteristically, and humorously, as a precious object within the glass casing of the traditional museum display.

Installation view, Iniva, Rivington Place, London, 2014.

Installation view, Iniva, Rivington Place, London, 2014.

Meeting Samb, I was struck by how he chose to communicate with me; without speaking. This deliberate strategy of refusing speech, and resisting explanation invites numerous interpretive approaches. It suggests conceptual and imaginative links to performance artists such as Marina Abramović (her new durational piece ‘512 hours’ is currently at the Serpentine Gallery, London). Similarly to Abramović, Samb’s performance practice speaks to the idea that the viewer (or the Other) completes the work; and silence emerges as a theme. At Iniva, sound (audible or absent) is an unmistakeably important aspect of the exhibition and central to the films by Bruyère. Samb works closely with Bruyère but without spoken communication. The work on the exhibition, in its entirety, made me highly conscious of how it is we construct meaning in relation to art objects and the sounds, gestures and performances of artists. The exhibition motivates me to consider how avant-garde movements through the twentieth century (notably Dada) have deployed opacity and methods of provocation and agitation. Passive consumption is disallowed in the experience of Samb’s work. We are drawn into processes of active engagement whether it is through the imaginative processes of responding to objects and their relationships or grappling with sound that refuses formal language and performs the right to be silent.

In my imagination, to refuse speech is a political act. It is a device that can obstruct the projections and assumptions of others. Speech and voice has a complex relationship to histories of authoritarianism, censorship and violence. All human subjects that have experienced structural prejudice on the basis of race, gender, sexuality and culture will know the de-humanisation of being spoken for, not as a human being or a citizen, but rather as an object and a site of projection. In the wake of these experiences the mobilisation of a voice might take different forms and one of these might be imagined as a kind of strategic silence.

Broadly speaking we are now accustomed to art practices that resist the idea of the singular, authoritative narrative but this is grounded in a forceful dialogue with History; and is not benign. Following the political and intellectual struggles of the twentieth century it is commonplace that historical knowledge, while located in dates and events, is not unambiguously objective, rational or empirical. Scholars, artists and intellectuals (situated, for instance, in feminist and post-colonial thought) offer damning critiques of the enlightenment rational-critical subject imagined as male, white and European. The forms that figures of power now take are no longer necessarily clearly defined but in the twenty-first century, historical struggles and traumas are resurrected and reinscribed. Warfare, displacement, prejudice and exile are as much a part of this century as they were of the last. Art historically, Samb’s practice is reminiscent of avant-garde devices initially deployed by Dadaists and subsequent experimental methods in art, film, theatre and literature. Situated in relation to the devastation of the First World War the Dadaist emphasis on absurdity, and the resistance to meaning located in formalised, linear language and thought is not simply apolitical.

Important to the historical avant-garde is the idea of the artist’s relationship to audience, institutional critique and the resistance to commodity culture. These kinds of impetus have been placed under scrutiny as artists are co-opted by the very institutions they have resisted. But arguably in current conditions produced by capitalism (stretched to exploitative and dehumanising limits) it is time to reflect on the ideals of the avant-garde and the particularity of individual artists working out of varying conditions and contexts. I asked Kouoh about her mobilisation (in conversation with me) of ‘relational aesthetics’ (in speaking about Samb’s work): ‘I am using it in a very literal way to talk about collaboration, proximity, love, friendship, works that derive from multiple inputs, works that are made because of the Other or for the Other. Works that put things and people in relation to the world’. [3]

Endnotes

[1] Extract from a conversation (Yvette Greslé, Koyo Kouoh, Jean Michel Bruyère, and the presence of the artist Issa Samb), at Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts), 3 June 2014.

[2] Ibid. Conversation, Iniva, 3 June 2014.

[3] Ibid. Conversation, Iniva, 3 June 2014.

Bio: Yvette Greslé is a London-based Art Historian, Art Writer and blogger. Supervised by Professor Tamar Garb she is completing a PhD on History, Memory and South African Video Art.

Info about exhibition:

Featuring films by Jean Michel Bruyère

Curated by Koyo Kouoh

Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts), Rivington Place, London EC2A 3BA, UK.

Exhibition runs through to 26 July 2014