Jean-Michel Basquiat is one of the most famous artists at the moment. He died almost 30 years ago at the age of 27. A lot of artists are influenced by him, especially black artists. His work is popular among young people. I am wondering how much of a poet he was. He started his career with texts on walls in lower Manhattan, in a lot of his drawings and paintings texts play an important role.

Rob Perrée on the poet Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Hollywood Africans, 1983 (Whitney Museum of American Art/ARS New York/ADAGP, Paris)

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, THE POET

Because of the countless number of exhibitions, not only in the US but all over the world, the work of Jean- Michel Basquiat is known by a large group of people. Because of his sensational, even crazy auction success – last May a skull painting of his was sold for $110.000.000 – the name Basquiat is ‘promoted’ from the culture section to the front page of all the newspapers and magazines and made into a brand name. Knowing that, why would a serious curator, who is not interested in blockbustering an artist, decide to make another exhibition? ‘Basquiat. Boom for Real’ at the Barbican Art Gallery in London proves that it is not only possible, but that it is actually possible to make a very interesting and surprising exhibition by focusing on the start and the inspirational sources of his artistry.

Since many text works were presented in the exhibition, it made me question how much of a writer or even a poet he had been.

*

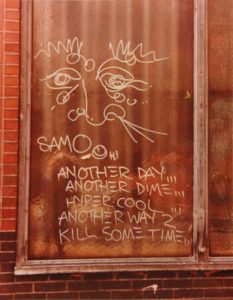

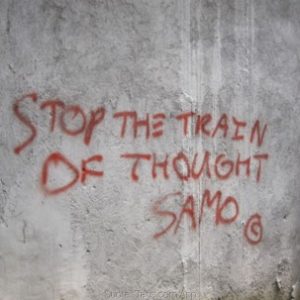

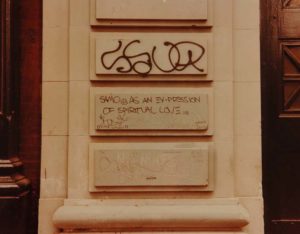

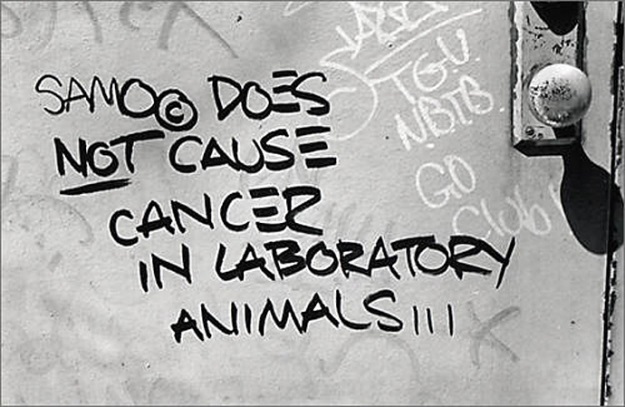

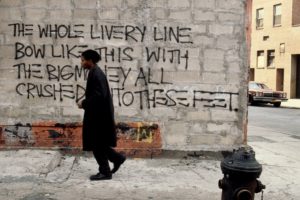

In the seventies and the eighties New York was covered with graffiti, spray painted or drawn images, signs (tags) or words on walls, trains, fences, in restrooms and on various types of surfaces. Expressions of a hip-hop culture that wanted to manifest itself in the public space. Sometimes to get a social message across but more often just to mark territory or to communicate with peers.

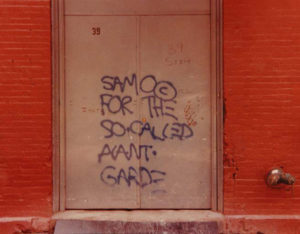

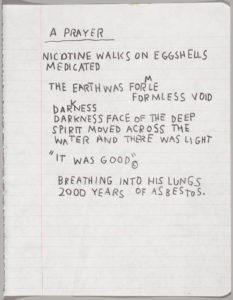

In 1978 Basquiat and his friend Al Diaz were walking around in SOHO and the Lower East Side, talking, joking, laughing, absorbing what they saw and heard. They left messages behind. They liked the activity of it, the performance. Basquiat did not use the traditional graffiti way. He wrote sentences on walls and doors. “It’s as if he were dripping letters.” (Robert Farris Thompson) Statements of one or a few more lines. Under or next to these words he put the tag SAMO©, a play on the phrase Same Old Shit. His texts draw attention not only because of his characteristic handwriting, but also because they were enigmatic, puzzling, cryptic. They triggered curiosity.

Often they looked as if they came from a box of words. Randomly combined. Sometimes the location clarified the content. Messages written on walls close to art galleries for instance, you could read as applications because of the specific context (SAMO© for the so called avant-garde).

For a long time nobody knew who was hiding behind SAMO©. When the weekly ‘The Village Voice’ ‘outed’ him, the announcement “SAMO© is Dead” appeared on walls. The mystery strategy was killed. Basquiat had to look for other ways to express himself with words.

Untitled Notebook (Front Cover), 1980-1981 (collection of Larry Warsh. Copyright © Estate Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar New York. Photo Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum).

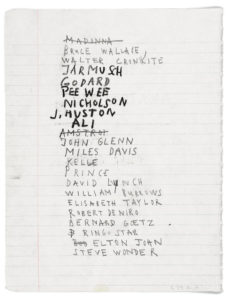

Notebooks would become a useful alternative for the walls. He started to buy them in 1980 and used them until he died. They did not function as sketch books, they had a life of their own. They were filled with slogan like sentences (the average man laughs 15 times a day), clusters of sentences around one theme which you could call a poem or a very short story (He puts a chalk mark on his back and watches him get hit by a car from a safe distance.), intimate thoughts, summaries (for instance a list of all the people he was influenced by or a list of chapter titles of Moby Dick), grouped sentences based on association, descriptions of ideas, philosophical remarks, elementary drawings as illustration of a title (Famous Negro Athletes), exclamations without any context (blue suit margarine men), streaked sentences which, Basquiat stated, deserved extra attention and were streaked for that reason etcetera. His words and images were rendered in ink, markers, paint and oil sticks.

Page from Untitled Notebook, 1987 (collection of Larry Warsh. Copyright © Estate Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar New York. Photo Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum).

Basquiat considered his notebooks part of his artwork. The story goes that he asked Rene Ricard, the first art critic who acknowledged his talent, to authorize them. The lay out of the pages is is proof of the conceptual character of the notebooks. He almost never wrote on the backside of a page as if he knew that they once would be showed in an exhibition. Words or sentences were spread out over the pages with ‘whites’ in between. A thought out placement, common for (experimental) poetry. Like in Concrete Poetry, he played with his handwriting. On some pages he wrote only one remark, for instance Three Missing Links. He knew that he, by doing that, added extra meaning to random looking words.

Knowing this, is it strange to call Jean-Michel Basquiat a writer, even a poet? He knew the value of words, the rhythm they can create; he knew the effect of space in between words; he knew what random words and sentences can do to each other, what a look does with words, how words can sound. As the critic and curator Dieter Buchhart said: “he gave eyes, ears, mouth – and soul – to words.”

I am wondering where this fascination for words came from. Even when he, later, painted or drew images the words and texts were never far away.

Untitled Notebook Page c. 1987 (collection of Larry Warsh (photo by Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum, © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, all rights reserved, licensed by Artestar, New York)

Basquiat dropped out of High School but he grew up in a middle class family where culture played an important role. Art (he visited museums with his mother), music but also literature. The Black Arts Movement, the cultural counterpart of the Civil Rights Movement focused on literature. Reading poetry was one of the activities they stimulated. Father Gerard Basquiat must have been familiar with it.

More important was the way Basquiat absorbed his environment. He picked up words and sentences from the radio and the television, he was well aware of the advertisements in newspapers and on the streets, he collected art books for the images, but in that way he must have encountered word works of for instance Dada- or Pop-Art artists, of Barbara Kruger, Richard Prince and Jenny Holzer, but also the words in the sketches of Leonardo Da Vinci, one of his favorite artists.

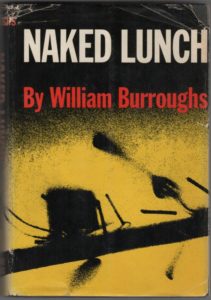

Basquiat loved the books of William Burroughs. In fact these books are a collage of words and sentences. Like his admirer, the old bard played with words. Books like the ‘Naked Lunch’ (1959) don’t have a narrative. You can step in on any page you want.

And, finally, his improvisation based wordplay could have been inspired by the improvisational jazz of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, two other heroes of Basquiat?

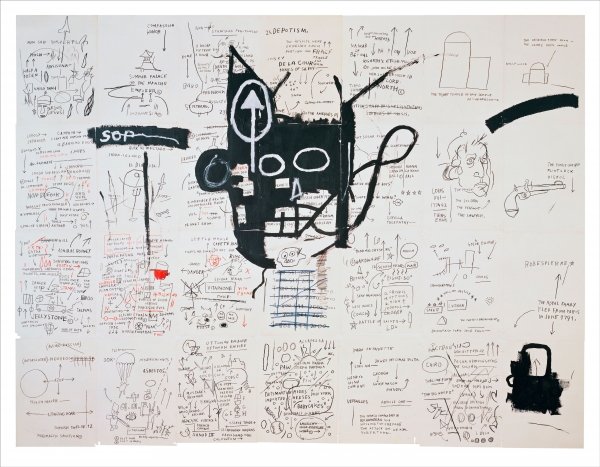

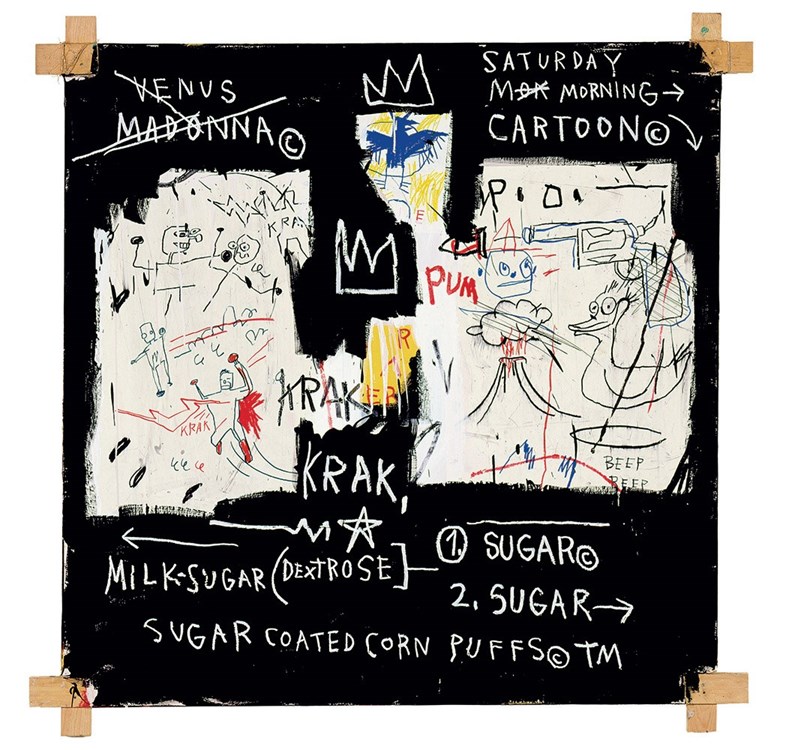

Some critics say that the early Notebooks prove that Basquiat was not yet sure in which direction he wanted to go as an artist: poet or visual artist. I don’t know if that is true. What I know and what I could see in The Barbican in London again: in many paintings and drawings the two disciplines are combined in a natural way.

Untitled, 1982-1983 (collection of Fred Hoffman. Copyright © Estate Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed Artestar, New York)

In some works he starts with the texts and puts images on top of them, like in Untitled, 1982-1983; in other works he mixes images and texts on the same level. By doing that the word becomes an image, one of the sources he appropriated. I use the word ‘appropriated’ because all the works are the result of a curious young man who wanders around and takes up everything he sees, hears and reads – he was an information glutton – and collages all these elements, in a personalized form, on his canvas or on paper. Appropriation was an accepted and popular practice in the 80’s. Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, Andy Warhol, John Baldessari, Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, they and many others did it.

A Panel of Experts, 1982. (copyright © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat / SODRAC (2016). Photo: Courtesy of The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts)

It is debatable to call these last paintings and drawings poetry, but the collage-way they are conceived, the awareness of the(visual) power of words that speaks from them, go back to the poetic texts he painted on the walls of Lower Manhattan in the 70’s and in the early Notebooks that he left behind.