Roy DeCarava died 5 years ago.

One of his most interesting projects was a book together with Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes.

‘The Sweet Flypaper of Life’ was published in 1955. It is out of print.

Alan Thomas wrote about this project:

(Originally published as “Literary snapshots of the sho-nuff blues,” In These Times, March 27-April 2, 1985).

“Who can dance to this bopping music? In the old days we used to like blues. And I still do. But now the kids don’t lean on the piano no more unless the piano is playing off-time.” The words are Langston Hughes’s and the images that inspired them those of photographer Roy DeCarava: a waitress singing to the blues, hands as expressive as her music; another woman (drink in hand, elbow on the bar, cigarettes strewn) in lonesome accompaniment.

Hughes and DeCarava’s classic integration of prose and photography, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, was first published in 1955. Out of print since 1977, the book has been given new life in a redesigned and magnificently produced edition by Howard University Press. Its reappearance should bring to attention an artist whom the photography establishment has often found it convenient to ignore. [Note 2009: Sweet Flypaper is again out of print, as are all of DeCarava’s books.]

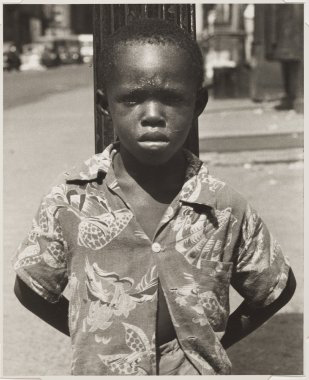

Roy DeCarava was born in Harlem in 1919. He trained early as a painter, working in the poster division of the WPA in 1938. Eight years later he began to use a camera in order to sketch ideas for painting and soon decided to devote himself entirely to photography. Edward Steichen, who later included several of DeCarava’s photographs in The Family of Man, offered early encouragement, and in 1952 DeCarava became the first black artist to win a Guggenheim fellowship in photography. The photographs in The Sweet Flypaper of Life—subdued pictures of everyday Harlem existence, from intimate family moments to street play and subway gloom—were made on that grant, but still DeCarava could find no publisher.

DeCarava’s photographs languished in a closet until he took them to Langston Hughes. “I thought Hughes would enjoy them because they were so much about people,” DeCarava told In These Times this February. “He was very touched and moved by the pictures and said, ‘Let me try to get them published.’”

Hughes found Simon and Schuster willing to bring out the book, but only on the condition that Hughes write an accompanying text. DeCarava at that point relinquished control of the project, giving Hughes some 500 photographs from which to make a selection. Of the people he had photographed, DeCarava told Hughes nothing.

The Sweet Flypaper of Life is not, then, a collaboration of writer and photographer, but a writer’s response to photographs, a phototext in the same category as Thom and Ander Gunn’s Positives (1966), Ted Hughes and Fay Godwin’s Remains of Elmet (1979), or Wright Morris and Jim Alinder’s Picture America (1982). Yet DeCarava’s images provide more than a mere occasion for Hughes’ writing. It is a measure of Hughes’ respect for the photographer that he engaged something essential in each image, pointing always to the pictures. Many of his passages close with a colon, allowing the photograph to complete the thought.

DeCarava’s trust in the writer paid off. Hughes organized the photographs around the musing of a fictional grandmother, Sister Mary Bradley of 113 West 134th Street, New York City, who introduces most of the subjects of DeCarava’s photographs as members of her extended family: daughters, their husbands and inlaws, grandchildren—particularly a trouble-prone grandson named Rodney who is Sister Bradley’s preoccupation throughout the narrative.

“I am still amazed today at the accuracy of his perceptions,” says DeCarava. “It was almost clairvoyance the way he characterized the people in the photographs. ‘Rodney’ was a good friend of mine, and he was just as Hughes described him. He had hit the nail on the head, and this happened again and again throughout the book.” With the help of DeCarava’s photographs, Sister Bradley describes Rodney’s girlfriends, his son, and toward the end of the narrative it is clear that her chronicle of life in Harlem is a fond but anxious representation of the world she must bequeath to Rodney: “I always did believe in looking out front—looking ahead—which is why I’s worried about Rodney…. What do you reckon’s out there in them streets for that boy?”

Pre-bop photography

Langston Hughes’s decision to particularize the photographs in The Sweet Flypaper of Life—to assign names and roles to the people in them and to see every street scene from one character’s point of view—was a choice that recognized DeCarava’s own aesthetic. “At some point,” says DeCarava, “it comes down to allowing the subject matter to dominate or the photographer to dominate. I always wanted more than just the subject. I wanted what I felt.” Although DeCarava’s photographs always refer to the social world, they are not (as Hughes recognized) reportage.

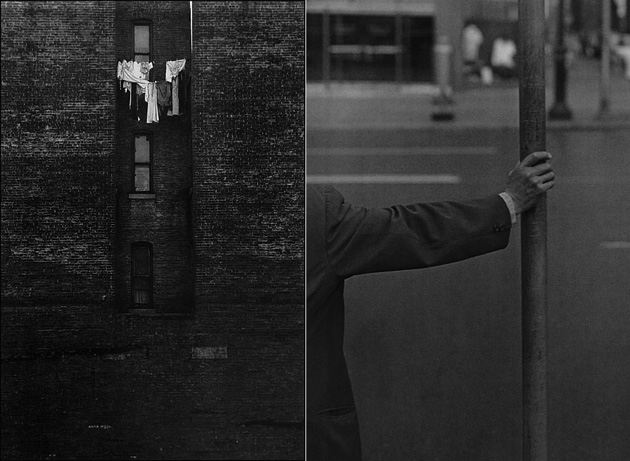

DeCarava himself is quick to reject the term “documentary” as descriptive of his work, for fear that it does not convey the personal quality of his vision. The autobiographical and metaphorical aspects of DeCarava’s photography are more evident in his work after The Sweet Flypaper of Life.

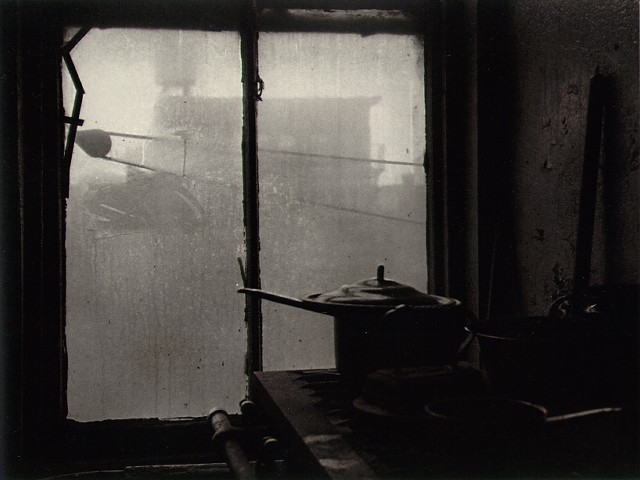

A turning point came in 1956 when he photographed a narrow, dimly lit hallway in a Harlem tenement: “It was one of my first photographs to break through a kind of literalness,” explained DeCarava in Roy DeCarava: Photographs (1981). “The literalness is still there, but I found something else that was strong and linked it up with a certain psychological aspect of my own. . . . The important thing is what it evokes in me in terms of my past and present. I can now see things of beauty within the body of its ugliness. Both because of and in spite of its contradictions, its origins and what they mean, it is still a beautiful image.”

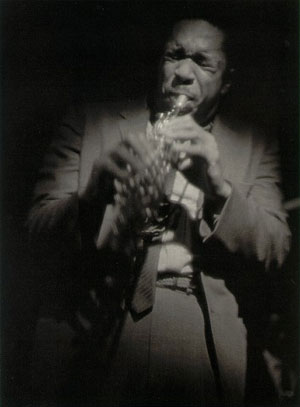

Although DeCarava’s photographs became more lyrical and expressive after The Sweet Flypaper of Life (particularly when he began to photograph jazz musicians), their deliberate style of composition remained constant. The strong visual ordering in DeCarava’s images suggests an analogy to traditional jazz and blues. One of DeCarava’s own definitions of jazz is “to be in tune”: “The moment when all the forces fuse, when all is in equilibrium . . . that’s jazz.”

As Hughes’ “Who can dance to this bopping music?” implies, DeCarava’s style is pre-bop, concerned more with the visual equivalent of melody and classical rhythm than bebop’s off-time chord structures. DeCarava, himself a jazz musician, agrees, adding that the linear structure of traditional jazz and blues is also more “literal,” while bebop’s “vertical” structure is the product of a more experimental concern with form.

Hughes’ “But now the kids don’t lean on the piano no more unless the piano is playing off-time” (DeCarava himself has likened piano to camera, both mechanical instruments of expressive potential) is prophetic of DeCarava’s fate in the photographic canon. Four years after The Sweet Flypaper of Life appeared, Robert Frank published The Americans, a book of photographs taken on his Beat- and bop-inspired road trips across the U.S. Frank’s work remained in a sense “literal,” but its style, like bebop’s, created itself in an improvisational search for new disharmonies. His was an ironic, skewed aesthetic at odds with DeCarava’s gentle humanism, and it still dominates much of fine art photography today.

Force of resistance

DeCarava’s portrayal of black American life has been comprehensive, embracing not only love and family life but protests, strikes, and arrests. A photograph from 1963 titled Force, published in the now hard-to-find 1981 book, shows how thoroughly DeCarava accommodated overtly political subject matter to his aesthetic concerns. The image is a closely cropped, almost abstract depiction of hands gripping the ankles of a woman. The arrangement of arms and legs suggests a formal exercise until one realizes that this is a photograph of a woman being forcibly dragged from a demonstration.

DeCarava has remarked that he was interested in using this photograph not to document a particular instance of brutality but to create an equivalent for an “insidious, almost imperceptible” kind of force in society. This “stronger and more pervasive” force, DeCarava points out, can also be used in the service of opposition. Indeed, the political element in his photography itself articulates quiet but powerful resistance.

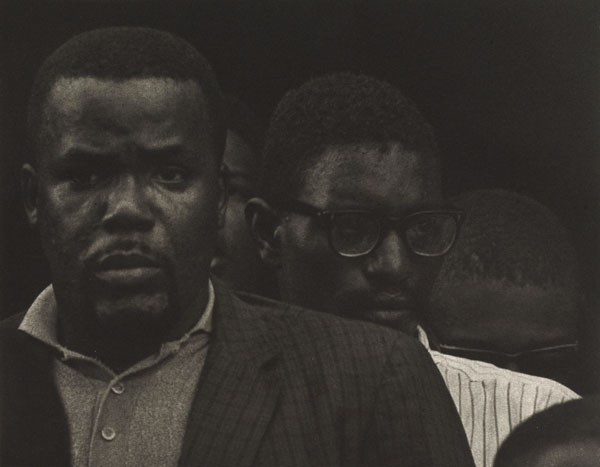

Toward the end of The Sweet Flypaper of Life come images of a picket line, an orator, and attentive listeners at a rally. Hughes’ text puts only a few words on each photograph: Picket lines picketing: . . . Talking about ‘Buy Black’: . . . ‘Africa for the Africans’: These details are part of a longer catalog of city vignettes recited by Sister Bradley. The impression conveyed is that of political struggle as part of Harlem’s very rhythm—no more obtrusive in DeCarava’s eyes than stick ball or parades or family ritual, but no less integral to black Americanexistence.

Seeing that Sister Bradley’s musings on Harlem are unified by anxious hopes for her grandson, one can turn again to the first pages of the book and see Hughes place the entire work in a subtly political framework perfectly suited to the photographs. Hughes opens the book with Sister Bradley’s refusal of a telegram from a divine messenger: “Boy, take that wire right back to St. Peter because I am not prepared to go. . . . For one thing, I want to stay here and see what this integration the Supreme Court has done decreed is going to be like.” Sister Bradley’s anticipation of social change mingles with her relish of family life, music, and the “fine people of our race.” The whole of it is life—sweet, sticky, and as political as it is private.

Edward Steichen has written that The Family of Man was concerned “with basic human consciousness rather than social consciousness.” It is a distinction Roy DeCarava would never accept.

Posted in memory of Roy DeCarava, 28 October 2009.

Alan Thomas is editorial director for the humanities and social sciences at the University of Chicago Press and a photographer. He can be contacted through his Web site, www.alan-thomas.com.

“I never work with light”-Roy DeCarava

Fragment from Nieman Reports, Summer 1998.

Roy DeCarava was born on December 9, 1919. His parents separated long before he got to know his father. His mother encouraged him in music and the arts, and he decided at age 9 to become an artist. As a youngster, DeCarava was a latch-key child who sold shopping bags or newspapers and hauled ice. At movies, according to one writer, “he absorbed the visual aesthetic of black and white films.”

At Textile High School, DeCarava was introduced to the work of van Gogh, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. His sense of art and his possibilities exploded. He graduated in 1938 and went on to The Cooper Union School of Art. After two years enduring the frustration of racism, he continued his studies at the Harlem Community Art Center, where such luminaries as Paul Robeson and Langston Hughes were a constant presence. Artists such as Romare Bearden, Robert Blackburn, Ernest Crichlow, Elton Fax, Jacob Lawrence, Norman Lewis and Charles White were living, breathing examples for the young black artists frequenting the center.

DeCarava shifted from painting to print-making, particularly serigraphy, and had his first one-man show in 1947 at New York’s Serigraph Galleries. He was soon making photographs to provide himself with material for his prints, and by the end of the 40’s he embraced photography as his sole medium of artistic expression.

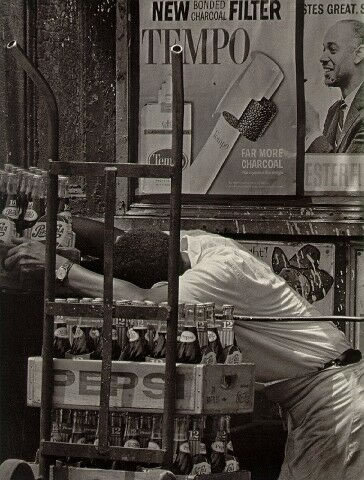

DeCarava’s change of venue occurred around the same time that the 35-mm camera became the instrument of choice for aspiring photographers. For him, it was not a weapon, but an instrument of expression that he used, surgeon-like, to delicately expose the soul of his people. DeCarava managed to capture the everyday, seemingly mundane, experiences of his community in a way that neither stigmatizes nor romanticizes them. Many have described the womb-like darkness from which his images emerge as dark and sinister. But to me, the light comes from within, and is therefore all the more precious.

His tireless pursuit of images that speak a universal language is what makes him an important example for other photojournalists.

When I look at his images, I am reminded of why photography is noble and inherently rewarding. There is an incorrect assumption that when we look at an image we see a subject outside ourselves. Not so, says DeCarava. “The subject is not really out there, the subject is just the beginning of in here,” he says, pointing to himself. “What you’re really doing is, you’re really going inside yourself, and describing yourself and what you believe in…. Every picture that you take is another word in your bibliography of experiences. You really don’t have to find a subject; when you have a subject, the subject really reminds you of something interior, and you hang on to that because that subject opened up the door.”

Whether it’s in the photograph of “Bill and Son” or “Three Figures, Halsey Street,” DeCarava’s images speak to humankind’s determination to prevail. His still lifes live; there is hope in his abstracts; affirmation resounds in “Curtains and Light.” There is light at the end of all of his tunnels.

Lester Sloan, a 1976 Nieman Fellow, is a contributing essayist to National Public Radio’s Weekend Edition and a freelance photojournalist living in Los Angeles.

“It doesn’t have to be pretty to be true. But if it is true its beautiful.” -Roy DeCarava

Courtesy and copyright: The Sherry and Roy DeCarava Archives