“Especially the group show in the main building of the Giardini park was of high quality. Because of the selection, but also because of the clever, inspiring installation. All the good things came together there.

Okwui Enwezor did it again. It sounds like an Obama slogan, but this edition will make a difference, especially for contemporary African art.”

Rob Perrée on his first evaluation of the Venice Biennial.

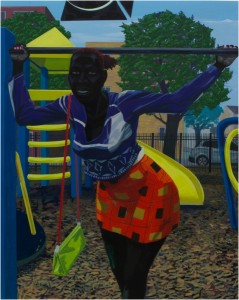

Kerry James Marshall, Playground, 2015.

VENICE BIENNIAL

Some Afterthoughts

1.

In 2002 the Nigerian critic and poet Okwui Enwezor (1962) curated the Documenta in Kassel, Germany. He showed the art world that there is more to art than art from Europe, the United States and other countries with a fixed place in the Western canon. He selected for instance artists from 8 African countries and artists from India, Lebanon, Iran, China, Cuba and Singapore. He denies that it was a strategy. In an interview in the weekly Vrij Nederland he says: “But I don’t wake up in the morning with the idea; God, I am the first non-western, nomadic, diaspora director of the Documenta. But that I have to show the period in which I live, as good as I can”.

Terry Adkins, Plinth, 2004-2015.

Strategy or not, his Documenta, which was visited by 650.000 people, changed the perspective of many of them. Certainly not all, because his concept was criticized a great deal as well.

This year he was the curator of the 56th Venice Biennial. He selected more than 35 black artists. African-Americans (Glenn Ligon, Terry Adkins, Melvin Edwards, Kerry James Marshall, Garry Simmons, to name a few), black artists from Europe (like Isaac Julien and Chris Ofili) but also many artists from Africa (Emeko Ogboh, Kay Hassan, Wangechi Mutu, Karo Akpokiere, Invisible Borders Collective etc.). When asked, he will react with the same words: “I have to show the period in which I live, as good as I can”, but that would be an understatement in this case. For the Americans and the Brits it is perhaps true (several of them are on the long list, but the shortlist is still white male dominated), for the Africans it could be true after this biennial, but selecting them now is still more a statement than a representation of the everyday art reality.

2.

One day before the official opening the critic Benjamin Genocchio published a review on artnet.news. He called the biennial “the most morose, joyless, and ugly biennale in living memory”. That is a personal opinion. A strong one, for sure. However, not a reason to get immediately out of your mind. But his motivation is dubious. He says; “(…) he (Enwezor) uses his authority as the first Biennale curator of African descent to validate artists from the world’s periphery, Africa especially (…)”. I would call that an attack ‘below the belt’. It questions the integrity of the curator and it denigrates a whole continent. It shows also that two days of previewing the biennial was far from enough to get rid of his prejudices and lack of knowledge.

That art has to be entertaining and not unsettling, another remark of Genocchio to prove the joyless and ugly character of the biennial, that is a personal opinion that I don’t agree with, but at the same time I realize that many blockbuster oriented museum directors follow the same way of thinking. At this point I belong more and more to the minority.

Barthélémy Toguo, The New World Climax, 2000-2014

3.

Genocchio is not the only one who criticizes the political character of the biennial. Many artists made political statements. A few examples. In his sound installation Emeka Ogboh let denied African refugees sing the German national anthem. Not in the least because of the almost perfect acoustics in the little chapel this work gives you goosebumps. Ibrahim Mahama covered the walls of a long, narrow path between Arsenale buildings with jute bags, roughly knitted together, which are produced in Asia, under dubious working circumstances, and are used in Ghana in the, not less dubious, cacao industry. In ‘Vertigo Sea’ John Akomfrah criticizes the whaling industry and makes a connection with black bodies washed up on beaches in southern Europe. Vik Muniz made a 45 foot boat out of Italian newspapers reporting the death of immigrants.

Of course the Venice Biennial is political. How can you be not political in the crazy world we live in? How can you be blind for the disasters that are taking place in many countries? The refugee problem – urgent especially in Italy – is only one of the many problems we tend to look away from. A curator who wants to reflect “the period in which we live” has to be open for artworks with a political content.

The critique is mainly focusing on the daily readings out of ‘Das Kapital’ of Karl Marx. An idea of the British artist Isaac Julien. I have to admit, not the most creative way of being political, his other works show more creativity, a bit naïve too, more a pamphlet than a work of art, but I don’t care. It is a clear statement that does not disturb me. I don’t feel beaten up with political theory, as one critic describes it. I listen a few minutes and go on.

What disturbs me more is when artists make work that limits itself to the little, private and closed off world they live in. Why should I be interested in navel gazing?

Wangechi Mutu, installation, 2015.

4.

The historical concept of the Venice Biennial is: two main group exhibitions – one in the Arsenale, one on the Giardini location, both curated by the chief curator – combined with country pavilions, organized and curated by the different national curators. Originally these national pavilions were all located in the Giardini park, but since there are more than 80 countries participating these days the Giardini is too small. The whole city is becoming playground for the different countries.

The first pavilion was the Belgian one. It was in operation in 1907. It is a modest building in contrast to the Russian or the American pavilions. These are architectonic monsters in stone. Belgium neighbors the Rietveld creation of the Netherlands, build in 1954.

In principle, every country can have it’s own pavilion. It is mainly a matter of money. They can rent a palazzo in the city and show their art in it. They can use a church and turn it into a mosque, like Iceland did this year. They can rent an old factory building and use it for whatever they want to use it for. All this has nothing to do with and is not the responsibility of the biennial organization.

That is becoming more and more of a problem. Physically it is impossible to visit them all. Unless you have a decent boat with a friendly mate who shows you around for two days. A bigger problem however is the quality. Many countries take the selection seriously, several countries want to make an artistic or political statement with it, but there are also countries that think that it is more important that their country is part of an international, respected event than to present the best art they can present. Especially this year there were too many bad national presentations. I was in houses and palazzo’s that were much more interesting and beautiful than the artworks in it (the traditional palazzo’s in Venice are a challenge. They force you to be really good).

All that bad art influences your general opinion about the biennial. Many visitors – I heard them complaining a lot – are blaming the biennial curator for it, but it is out of his reach to change this situation. It is becoming a mess and they – whoever they are – have to do something about it. Why not a curatorial team – independent from the main organization – that would operate as artistic advisor? To begin with. To stop at least the worst of these presentations.

Invisible Borders, Trans-African Project, 2015.

5.

On the first day of the press previews I saw them already. The billionaire boats. Moored at the quay of the Arrsenale location. Probably build in Friesland, The Netherlands, because they are specialized there in realizing the dreams of the rich. I am talking about collectors who are using the opportunity to supplement their art collection in an early stage. Of course, the biennial is not commercial, it is not an art fair, but at the end every artwork is for sale. Most of the artists are represented by galleries and nobody can stop these galleries from organizing parties on the spot to support their artists. The galleries were asked to stay low key, but I am sure that I could have find out what I had to put on the table for an Ellen Gallagher, a Melvin Edwards or a Chris Ofili.

It is impossible to organize a biennial that’s not commercial. It is commercial money that makes events like this possible. And if companies are willing to invest they don’t do it out of generosity, they want the money to come back. One way or the other. Nobody has stopped Swatch from putting a big tent in the middle of the biennial site with terrible art in it. Without Swatch there was no 56th edition of the Venice Biennial. Enwezor knew it and obviously decided to live with it. Although his political statements are impotent pinholes in the full belly of commerce, he made them anyway. They had to be made.

Art is more and more about money, record sales (“Christie’s New York first ever record sale of a $1bn a week” scream the headlines), artists working directly for auction houses, artists thinking more about marketing strategies than about concepts and ideas. Adrian Ghenie – a great Hungarian painter – speaks his hart out in an interview in the New York Times: “It is frustrating to see people making so much money so quickly. I feel I am being speculated. It’s not me. It’s the new art world.” A curator of a big New York museum explains the absence of African in their collection by saying: “Exposure of any artist has to do with market representation.” She is not fired because of this remark, she is just representing “the new art world”.

6.

In spite of the negative aspects I was talking about, I liked this edition of the Venice Biennial a lot. I saw many good works that I haven’t seen before from all over the world (Terry Adkins, Adrian Piper, Invisible Borders, Wangechi Mutu, John Akomfrah, Sammy Balojl, Charles Gaines, Ellen Gallagher, Theaster Gates, Emeko Ogboh, Barthélémy Togue and many others). Especially the group show in the main building of the Giardini park was of high quality. Because of the selection, but also because of the clever, inspiring installation. All the good things came together there.

Okwui Enwezor did it again. It sounds like an Obama slogan, but this edition will make a difference, especially for contemporary African art.