Insulated in the bubble, Kannemeyer does not see the causal connection between ruling party’s political compromise and his own sanctuary. That his paint runs dry on this matter isn’t an accidental omission, but a typical white attitude.

South African critic Athi Mongezeleli Joja on the last exhibition of Anton Kannemeyer.

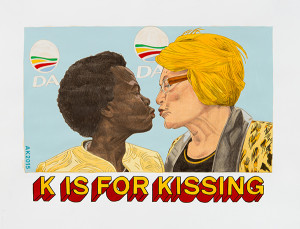

K is for Kissing, 2015.

Anton Kannemeyer’s white culpability.

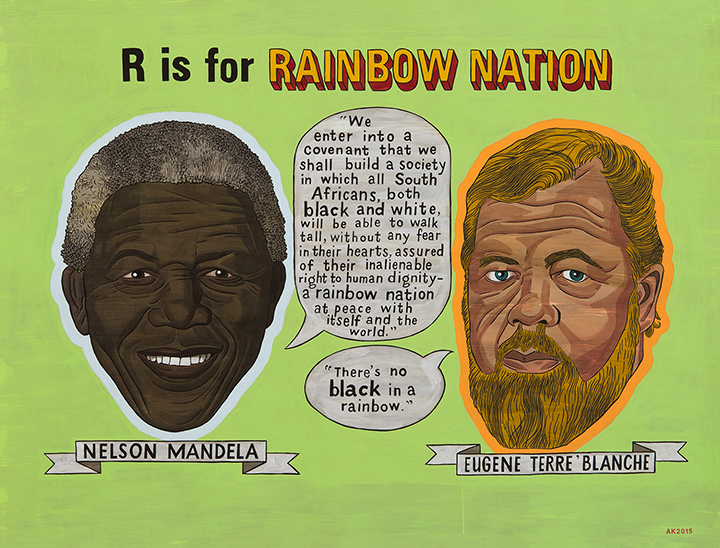

Anton Kannemeyer’s ‘E for Exhibition’ is his fifth solo show at Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg and happens in the midst of “exciting” times. University students, throughout the nation, have finally rendered institutions of higher learning ungovernable and shutdown demanding free education and an ending of worker’s exploitation. Workers, civil and radical groups are calling for state accountability on human rights abuses committed by and in protection of “white monopoly capital”. Like an orchestra without a conductor, these protests have disrupted the daily routines of civil life and threaten a national shutdown. They’ve stripped away the veil of the “society in harmony” and revealed the stark contrasts of its racial inequalities that have been normalized since 1994. Civil society in South Africa is no longer an objective space for all people. The turn of events points us to the fictive veneer of freedom and the sordid effects of post-1994 compromises and reconciliation without justice.

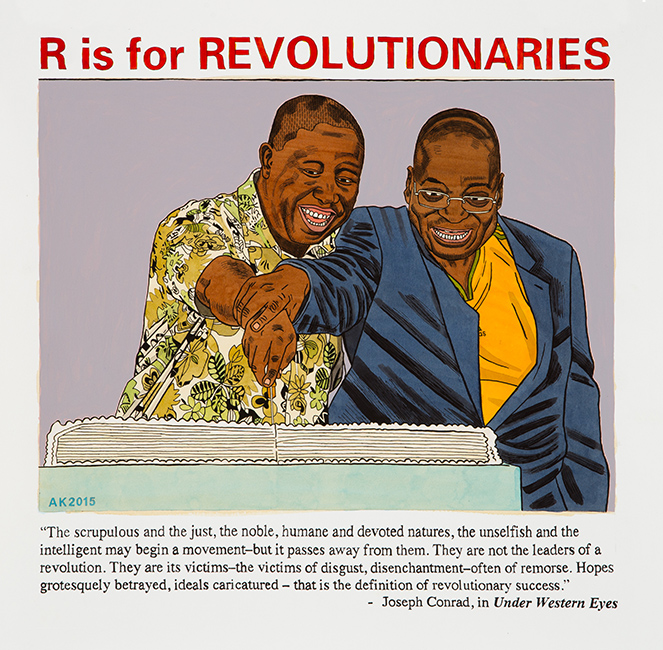

R is for Revolutionaries, 2015.

Kannemeyer’s exhibition of a mix of political satire and paintings occurs amidst these events. A series of painterly caricatures, typical of his now tired tricks, are a desperate gasp for critical practice, which simply trade insults. Like a little karaoke of insulated white liberals, at odds with the ruling party’s gross administration, the resident artist sings the club’s favorite tunes to an enchanted audience falling off chairs in stitches. This kind of satirical representation, while satiating the appetites of those disheartened by president Zuma’s reign, have infuriated others. Emotions are high, either way. Kannemeyer’s labor remains here… unwavering. He delivers his unquestioning objects like a conveyor belt retches out products in a sweatshop. Everything is available for laughter in Kannemeyer’s oeuvre, including the artist’s own life.

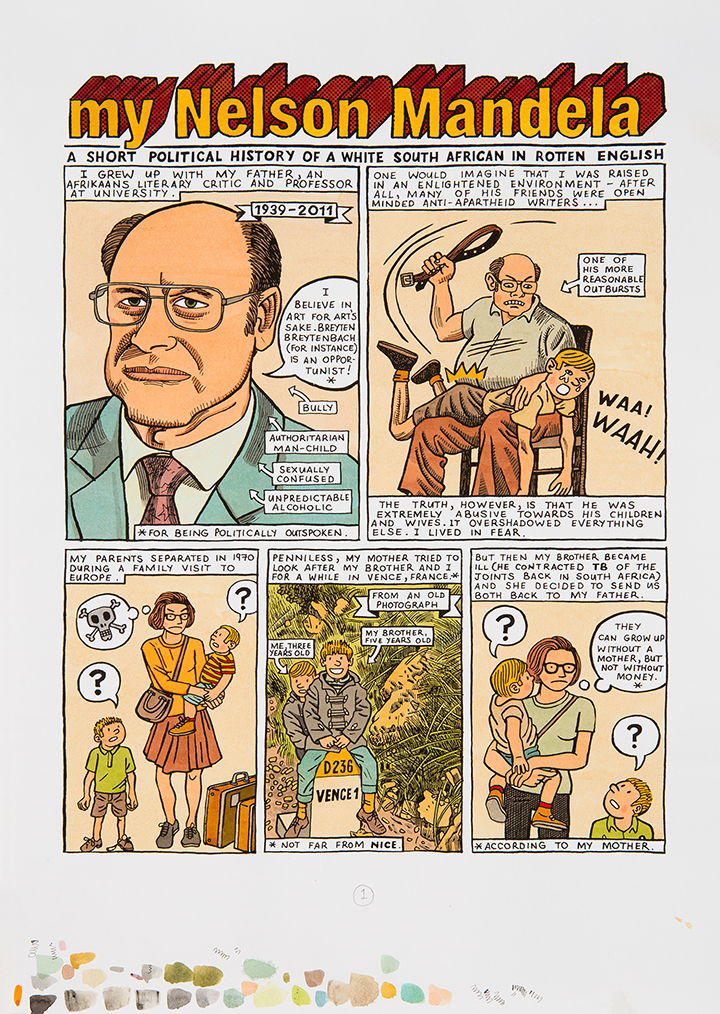

My Nelson Mandela, 2015.

My Nelson Mandela, 2015.

In his ‘My Nelson Mandela’, a comic strip that takes us through the artist’s encounter with political consciousness, Kannemeyer not only pokes fun at himself but also takes us through his more private issues. However, this deferral to autobiographical accounts is no new feature in the artist practice. The bald figure, tallish and often with a pervert’s demeanor is him – Joe Dog. Or even the swings he takes against white people and so forth, which give us a satisfying illusion that we are all democratically subjected to the satirical scrutiny of the artist, are also not new. They are as old as his so-called Bitter Comix. On the one side this is the dark side of classical comedy: its use of laughter as a sedative, temporally draws us out of our misery and reduces our tensions with unbridled innocence. Clowns or satirists are always known to defy social constraints sometimes by just publicly performing self-ridiculing stunts. They become the subject and object of their own obscene exhibitionism but without risking the actor’s real human status.

Like a comic, Kannemeyer’s disclosures are part of a larger troublingly trendy discourse of white confessions and penchant to “appear strange”: habitual declarations of complicity and culpability, that claim to circumvent white supremacy . This performative cleansing ritual of conceding to the obvious is hypocritical and pedantic. It does not obliterate racism but inadvertently conceals and immortalizes it.

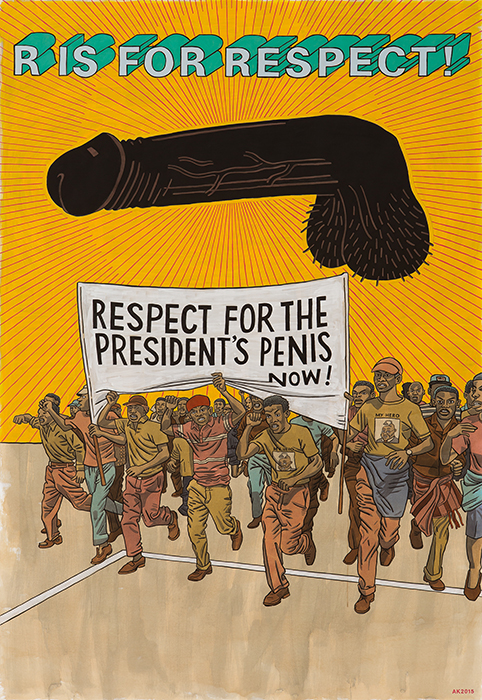

R is for respect, 2015.

Isn’t this what we can see from the show’s curatorial strategy as well? The fact that the first room, which welcomes the viewers, is dominated by generous display of more autobiographical work on the one side, as it were a sweetening passage leading to the more defamatory narratives of second room.

What can we say about the rest of the show, except to point to its reliance on the over recycled abject, stereotypical and biological tropes as means of “seeing” black people? Kannemeyer is beholden to this type of visual archive not only to dramatize his art, but also to find psychic and social balance. After all, to articulate a discourse on wickedness, the world relies on the black body as an incentivizing prop. For a coherent ethical and critical take, Kannemeyer’s work cannot look anywhere else but in these ready made and historically coded colonial visual template. Though some can repudiate Kannemeyer’s repertoire of sensational but insensate images as tired and routinized, they nevertheless are the kinds of images reside in the white unconscious. For the artist, President Zuma is not corrupt, as we would think all politicians are, but his being is an embodiment of corruption, penis, violence and stupidity.

R is for Rainbow Nation, 2015.

However relying on the perspective of the pervading decolonizing agenda, we encounter several omissions in artist Kannemeyer’s work. Or should we call it an unscrupulous criticism? What appears as an antagonism between Kannemeyer and Zuma is nothing but a momentary discord between old friends. Secondly, Kannemeyer’s very existence is implicated and called into question – as the existence of a lie, lived and possible at the expense of the black majorities. Because the artist is fixed to white common sense and sensation, he darts past this living complicity. White supremacy, which issues white people privilege, is not merely something lingering in an archived past, and which out of empathic declaration be bettered, but an excess of legacy persisting undisturbed into the post 1994 reality. Insulated in the bubble, Kannemeyer does not see the causal connection between ruling party’s political compromise and his own sanctuary. That his paint runs dry on this matter isn’t an accidental omission, but a typical white attitude.

E for Exhibition isn’t a visual criticism of the state of things but a cover up of white culpability.