“I begin to understand that perhaps it is not so much that she is against interpretations that deem her drawings sinister or dark, but rather that she hopes a few intuitive spectators will understand that they project their own emotions on to what they see. More than that, she wants me to acknowledge that the agony and the ecstasy can be felt simultaneously and equally, and that life often exists in the grey.”

Zihan Kassam on the ‘Straightjacket’ series of Beatrice Wanjiku.

Lifts beyond conception.

Inside Beatrice Wanjiku’s Straightjacket

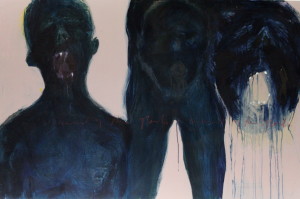

Even before her ‘Straightjacket’ series, featuring mortals physically restrained by an institutional vest, art critics were already referring to the expressions in Beatrice Wanjiku’s figure drawings as captive, confined and tormented. When I heard that she had not expected so many people to interpret their expressions as agonized, I became curious. How could Wanjiku’s contorted, amorphous figures, with their mouths wide open and teeth exposed, be anything other than incarcerated or tortured souls?

To get the real story, I decided to visit Wanjiku at her home studio in Ngong. At first her animated temperament and extroverted personality seem to contradict the obscure, inscrutable feel of her work. But after heavy dialogue, I started to understand and appreciate how Wanjiku thinks. The philosophical insights she shared were inspiring, and made my journey to Kajiado County worthwhile.

The Strangeness of my madness.

Wanjiku paints in what was once her family living room growing up. Long canvases in portrait position reveal nebulous sketches of unusually susceptible characters. Her new series bears the same creatures as the old: loosely defined individuals with highly emotive expressions. The same souls I have watched evolve over time. Very quickly it becomes clear that Wanjiku’s work is an organic process that cannot be segmented into different series, other than for documentation and exhibition purposes.

Lifts beyond conception II.

Her work occurs in a kind of ‘visual time’, revealing the same overwhelmed human beings, morphing as they experience more of the good, the bad and the ugly of this world. As they question the peculiarities of society and their role within it, they try on many hats or modes of existence. Certain physical elements in her paintings manifest and others disappear. For example, the x-ray radiographs that she once incorporated into her Immortality series are gone and the white straightjacket is in. But Wanjiku’s core image remains consistent: resilient characters that survive the trials and tribulations of time.

The sentiment of the flesh.

So are all Wanjiku’s paintings about her own experience then? “Although I am the point of origin of my work, and although of course it all starts with me and my experience, it is not just about me. It is about us, about people, all of us going through similar experiences with different ways of expressing ourselves.” She explains how the people she paints are a study of the human condition; of the struggle between the social self versus the internal self. She believes that most people are afraid to take a real look at themselves, to accept their vulnerability, their fragility.”Instead we wear masks to cope”.

We are who we were.

In society where norms are of our own construct, where we are expected be to be married by a certain age for example, or commit to an acknowledged career path, Wanjiku observes that those who don’t fit in the box are forced into a metaphorical straightjacket. We are castigated for being non-conformist. For those who decide to live life a little differently, the punishment can be far worse than the crime. We are shut off from certain circles, maybe even imprisoned. Wanjiku seems to be exploring the excessively negative repercussions suffered by those who march to a different drumbeat.

Out of this mess.

And so as she explores the imaginary borders and margins we use to contain, control and evaluate our encounters, Wanjiku’s shadowy figures continue to react to the contrived, irrational expectations of society. With their internals exposed in some of her figure paintings, and their bodies dissolving into the abyss, there is a visceral corporeality about her depictions; a focus on the body and then the deconstruction of it as yet another impediment in our search for higher meaning. As Wanjiku’s poignant souls yearn for truth or perhaps more divine knowledge, their bodies are rendered futile, secondary. Existing in the flesh has become a bizarre, overrated and cumbersome experience. And without physical definition or gender, their eccentric facial expressions are heightened, even though some of us still can’t put our finger on the exact emotions. A strange paradox, their gestures are both unintelligible and potent at the same time.

Effacement.

So again I ask, what exactly are the emotions felt by Wanjiku’s poignant souls? In her own words, she explains that, “When you see these individuals with their mouths wide open, please remember that elation and pain sometimes bear the same expression. For a while I have been studying the human predicament, the thin line that exists between empathy and the lack of compassion.” As Wanjiku tries to pinpoint her message, I begin to understand that perhaps it is not so much that she is against interpretations that deem her drawings sinister or dark, but rather that she hopes a few intuitive spectators will understand that they project their own emotions on to what they see. More than that, she wants me to acknowledge that the agony and the ecstasy can be felt simultaneously and equally, and that life often exists in the grey.

The strangeness of my madness IV.

To set the record straight, with Beatrice Wanjiku’s consent of course, I take a stab at what I think is an apt description of Beatrice Wanjiku’s unusual figure-mortals. What happened to these sensitive souls? Perhaps they began in the world as unsullied souls, naturally questioning and reacting to the strange societal constructs one has decided to accept as fact. Then, with time, as they experience happiness and pain and the multifarious emotions that Beatrice Wanjiku hopes we will catch in their faces, they come to realize that the world doesn’t quite operate in a fair way. When they become angry in their righteous quest for justice, we put them in a straightjacket, where they can do no harm and no good…