“There is a challenge being made about seeing and looking. The seeing is what happens on social media, but the looking is what I’m asking you to do. The looking requires thought, it requires engagement, it requires awareness, it requires inquiry, and it requires presence.”

Sasha Dees quotes Ebony G. Patterson

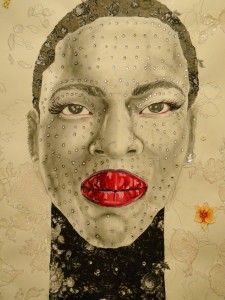

II Rosez (detail), 2014.

Ebony G. Patterson

Striving to make the unseen visible

Dancehall is at the center of Jamaican musical and cultural life, from its roots in Kingston in the 1950s up until today. Dancehall, a culture that encompasses music, fashion, art, community, technology and more, conquered the globe. Many of today’s global music and fashion styles can be traced back to Dancehall. Ebony G. Patterson came of age in the midst of it in Kingston. She also experienced its widespread influence firsthand when she moved to North America to get her MFA in printmaking and drawing in St. Louis. Dancehall in all its aspects and universality has been a big inspiration in Patterson’s work.

Of 72 Project (detail), 2012, digital prints on hand-embellished bandanas, 73 bandanas, 21 inch x 21 inch each. Commissioned by Small Axe Magazine and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Arts Grants.

Patterson is no silent bystander. She is an active participant in the culture and is using “her language and storytelling” to make the unseen visible. The Of 72 Project is Patterson’s commentary on the extraditing of Jamaican drug lord Christopher Dudus Coke (1). America requested his extradition in 2009. Jamaica initial refused but the government relented and gave a warrant for Coke’s arrest in May 2010. Immediately Kingston was placed under a state of emergency and 72 alleged supporters of Dudus were killed. Mostly young men and one woman, these masked martyrs became Patterson’s subjects. It was not revealed who was killed. Patterson with her work asks her government and the community at large to reveal the identities of the victims. The work makes you wonder: Why were these young bodies buried together with their identities? They are young people, human beings. We don’t know who they are or their potential. Why don’t we care?

Untitled (Species) , 2010-2011, drawing, paint, collage on paper.

Patterson also investigates gender roles and their contradictions in both Dancehall and Gang Culture. International audiences became acquainted with the violent anti-homosexual views in Jamaican Dancehall when Buju Banton’s “Boom Bye-Bye” (2) hit the record stores in 1992. As a result, his European concerts were cancelled due to the music’s call for violence against homosexuals.

Patterson went on to make a series of paper works that include drawing, painting, collage along with a modest use of glitter and sparkling fake jewels referencing bling culture. Her works drip with irony as they highlight the dancehall fashion of Jamaican men bleaching their skin and plucking their eyebrows, all while displaying extreme homophobia and machismo.

Having gained interest from curators who saw her work in group exhibits organized by Tumelo Mosaka (Brooklyn Museum, 2007) and Christopher Cozier/Tatiana Flores (World bank, 2011), it was the image of her paper work in ‘Crossroads’ which Holland Cotter reviewed in the New York Times (2012) that brought Patterson to the attention of the entire art world and it’s collectors.

Untitled (Lightz I), 2013, mixed media on paper, 81 x 148 inches.

Untitled (Lightz I), 2013, mixed media on paper, 81 x 148 inches.

That attention turned into more space and larger budgets which gave Patterson permission to go “all out” like the dancehall culture that inspires her work. Portraits evolved into group scenes. Patterson hired models, mostly men and children, to stage scenes in her Kingston studio for the camera. Those photographs then form the basis for the works on paper—initially two dimensional images, but the works became much larger and more elaborate in use of materials such as gold leaf, glitter and sparkles, textiles.

Untitled IV- beyond the bladez (study) mixed media on paper, 30 x 22, 5 inches, 2014.

Patterson shared that one night in Kentucky where she teaches during the school year, she went to Walmart late at night to quickly get some materials and discovered a selection of tapestries in the store. Tapestry and quilting are American traditions, and not widely used in Jamaica. Intrigued, she sent one of her photographs to a commercial weaver to create a tapestry using computer imaging. One could relate this to femage but in the case of Patterson it seems to relate to her theme and subject: Dancehall and the ‘gender-bending’ within. Patterson says she has never left painting. For her, working on the tapestries with needlework still feels like painting a canvas. The thread, she says, is like a brush stroke and collaging with textiles and other objects onto the tapestry feels like working on the canvas with different layers of paint, texture and structure.

Installations developed next. Patterson successfully creates a feeling for the viewer of wanting to be part of the scene. Who doesn’t want the confidence that the models express, to show off the clothes, drink the expensive bottles of liquor, and rock the sparkling bling adorning neck and ears? Patterson seduces us with bling, glitter, sparkles and most of all, attitude. Figures look down on viewers from above and in response viewers want to be there on that wall, on that platform. It’s done. We’re mesmerized and lured into Patterson’s storytelling wanting more and more and more, no sleeping time for us yet.

Swag Swag Swag, f rom the Out and Bad series, (installation view), 2011 – 2014, cotton, velvet, lace, plastic, and mixed media

Having won over her audience and created an expectation of amped-up glamour, Patterson’s new stories turn out a bit different than expected. Suddenly, the figures are lying down. Partly hidden, it’s unclear at first whether they are sleeping, or resting peacefully.

Two birds beyond the bladez (detail) , 2014, Mixed media on paper, 90 in x 89 inches, (2 parts: 90 x 43 inches; 90 x 46 inches)

In more recent work, Patterson stopped photographing scenes instead collecting images from social media and newspapers randomly reporting on people nobody seems to really know or care about. The kind of subjects one immediately forgets with the next image that pops up.

Violent deaths of people from the lower classes of society, the have-nots, often go unacknowledged. Working with pictures of people who were killed, shot, stabbed, raped in retaliation, robbed, or the victims of accidents, Patterson refuses to allow viewers to get away without giving these lives any thought at all. She makes us see, look, think and question what’s going on, what happened, who is this. She makes the initial thoughtless report a story that matters, transforming the unidentified, unseen victim into a visible human being who matters.

In Rest-Dead Treez, 2015, mixed media jacquard weave tapestry with handmade shoes and crocheted leaves

Her paper works have become tapestries and the people in them have ‘lost’ their heads. Viewers witness only genderless bodies of adults and children. The works move from the wall to the floor, becoming more and more elaborate. Camp bombastic aesthetics, the ‘brushstrokes’ become more dynamic, dancing over the ‘canvas’. The ‘paint’ more layered and textured, with more objects, crochet, beading, gems and the now-signature use of pounds and pounds of glitter.

Where we found them, 2014, cotton, plastic, lace, glitter, and mixed media, 96 x 72 inch.

Where we found them, 2014, cotton, plastic, lace, glitter, and mixed media, 96 x 72 inch.

Installation view Dead Treez, MAD museum, 2015.

Patterson credits Krista Thompson (3) and her book on the use of light in Diasporic cultures on making her aware of the illumination in her work and material choices. This light and illumination are tools used for centuries by artists to make the unseen visible. Patterson has said that this new awareness influenced her understanding of how best to install her work, selecting colors for the walls and how to light the works, something she has become very particular about.

In the end, it all draws attention to the victims. Because of the work, viewers want to know who these people are and what their stories are. This is Patterson’s aim. She wants us to evolve from accidental consumers of social media, casually flipping through newspapers to conscious viewers who really ‘look’ or at least think about how we are engaging with all that we are exposed to nowadays.

In her current solo show at Museum for Art and Design in New York one of her statements reads: “There is a challenge being made about seeing and looking. The seeing is what happens on social media, but the looking is what I’m asking you to do. The looking requires thought, it requires engagement, it requires awareness, it requires inquiry, and it requires presence.”