Successful artworks have the ability to instruct or persuade the populace, to give new meanings or perspectives on issues, to provide new knowledge or to build ones capacity in empathy for a certain cause. The use of art can provide a setting in which people can discuss issues, form connections, and potentially take action. Just how much people take away from this experience is difficult to tell.

Join the discussion with Craig Halliday.

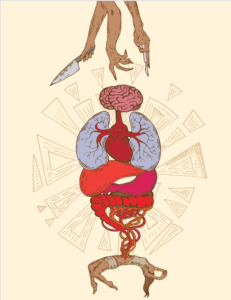

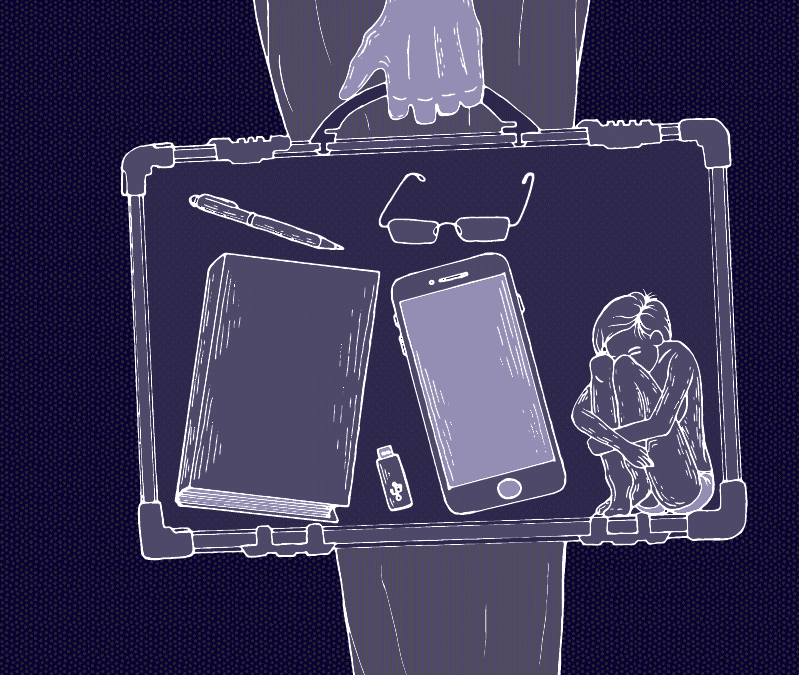

Brian Omolo, Insurance Policy.

What can art do?

‘What can art do?’ was the title of a discussion held at the Shifteye Gallery, Nairobi. The discussion was part of the project ‘Art to End Slavery’ (A2ES). A2ES is an awareness raising art project – developed by Nairobi based NGO ‘Awareness Against Human Trafficking’ (HAART) – that “aims to bring attention to human trafficking in Kenya…in an exciting way that will engage public participation”. (1) It looks to achieve this through collaborating with local visual artists and then exhibiting their artwork at an annual art exhibition which tours Nairobi and other parts of Kenya. A2ES states that it uses “forms of art as a tool for communication” in which “artists will use their skills to create visual representations of human trafficking” that will “help in disseminating the information about modern slavery to the public”. (2) This short article critically examines the role of art in this project and aims to answer the question of ‘what can art do?’ By assessing the role of artworks and the social spaces created by holding art events, I enquire what the strengths and weaknesses of this exhibition are – in terms of art’s extrinsic value, a means of providing new knowledge and building empathy as well as extending the public sphere and arenas for civic engagement.

Human trafficking in Kenya

According to the United Nations, human trafficking has three core elements: The act of trafficking; the means of trafficking; the purpose of trafficking. (3) In Kenya forced labour is the main form of human trafficking for men, women, and children – though sex trafficking is also rife. The country has become a source, transit and destination for these forms of human trafficking (4) – which are reportedly the highest in both Central and East Africa.(5) Forced labour, particularly of children, includes domestic service, agriculture, fishing, cattle herding, street vending, and begging; though they are also manipulated in prostitution – notably in Kenya’s coastal regions and cities. Lured by the prospect of well-paid work Kenyans also migrate to other African Nations, Europe, the United States and the Middle East – where they have been exploited in massage parlours and brothels, forced labour or domestic servitude. People have also reportedly been trafficked for military service, forced marriage, and ritual purposes. Poverty and unemployment are the main factors contributing to human trafficking – the socio-economic profiles of those trafficked are those with a low income or in poverty, low levels of literacy, unemployed, a desire for well-paying jobs, experience domestic violence and social exclusion.

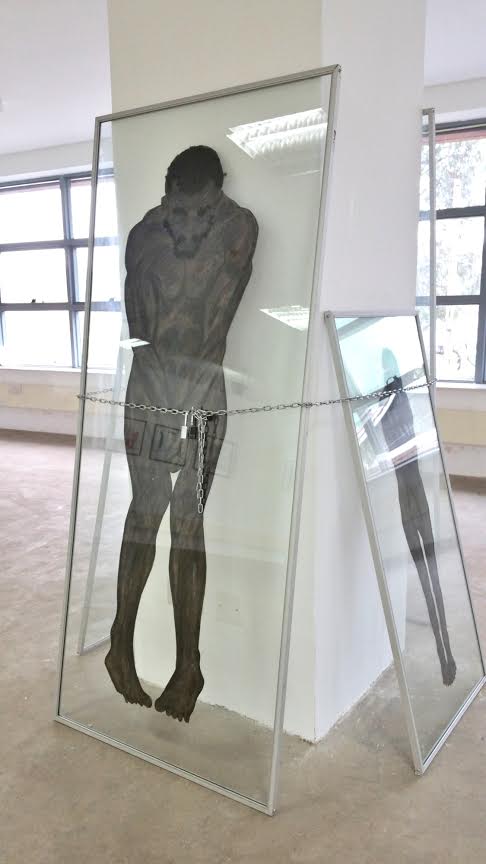

Samuel Githui, Let Them Go.

The exhibition and artists

The 2016 exhibition, (6) titled ‘Telling their Stories’, – which focussed on victims of human trafficking – coincided with the ‘World Day against Trafficking in Persons’. (7) The exhibition showcased work by over 20 artists and included painting, photography, installation, film, digital art, illustration and mixed media. (8)

Earlier in the year there was a call for artists to participate in the 2016 exhibition. Those chosen were invited to a one day ‘Master Class’ at the ‘Dust Depot’ – an art-centre in Nairobi. During the day staff from HAART and this year’s project partner PAWA 254, (9) along with the selected artists, had a discussion about human trafficking. The second half of the day saw veteran artist Patrick Mukabi, lead an artist workshop – which seemed relevant for those artists who were still early on in their career.

The opening night of the exhibition had live poetry, music, painting and dance; as well as short speeches by invited guests from the ‘United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’ (UNODC), the ‘Inter Governmental Authority on Development’ (IGAD) and HAART. The artworks, which numbered more than 40, were displayed in a large open plan room, which gave the works space to breath and the audience freedom to move whilst surrounded by representations of suppression.

The artworks dealt with the multifaceted nature of human trafficking – this included imagery representing the act of trafficking with humans sold and transported like a commodity, or recruited into jobs that at first seem promising; other artworks dealt with power relations and showed how trafficking is done – such as through false promises, coercion and violence, or the upkeep of traditions; the intent of trafficking was also depicted, with themes of sexual exploitation, ritual purposes, domestic work and child soldiers.

What can art do – can it really end slavery?

The extrinsic value of art

During the discussion of ‘what can art do?’ Mbuthia Mainia – an artist and curator who was moderating the talk – asked the important question of ‘can art really end slavery?’ The director (Radoslaw Malinowski) and Project Consultant (Sophie Otiende) of HAART gave passionate replies, though unsurprisingly acknowledge that art could not end slavery (at least not on its own) – the title was chosen for its impact. Both Radoslaw and Sophie did nevertheless discuss the extrinsic value of the artworks. The proceeds from the sale of artworks will be donated to assisting victims of human trafficking which could potentially raise a significant amount of money. HAART depends to a large extent on funding for its programmes – which, according to Radoslaw, has in the past intervened to stop a number of people possibly on their way to be trafficked. HAART also supports past victims of trafficking to build new lives and it has very recently opened a rescue centre for victims of trafficking in Kenya. However, the purpose of using visual art in this project was not for its monetary value – artworks depicting human trafficking and telling the stories of victims do not always sit comfortably on someone’s wall. Therefore it is important for the ‘value’ of these artworks to provide more than the income they can generate.

Art as knowledge formation and creating reflective individuals

According to Alana Jelinek – author of the book ‘This is Not Art: Activism and other ‘Not-Art’ – art practice and artworks can be seen as a knowledge forming discipline, because at times art is able to articulate and embody another way of seeing. This view is shared by the likes of Jacques Ranciere when he talks about ‘critical art’ which is an “art that aims to produce a new perception of the world, and therefore to create a commitment to its transformation.” (10) Likewise Chantelle Mouffe argues that art’s capacity lies in the fact that it can “make us see things in a different way, to make us perceive new possibilities”. (11) However, Jelinek comes back to state that “simply exhibiting virtues and vices…does not necessarily improve human behaviour – it is very difficult to find anybody who is actually ignorant of such things.” (12) It is this last comment by Jelinek which highlights, in my view, what makes some artworks stronger than others in this exhibition – in regards to their ability make one feel more acutely aware of human trafficking in order for us to do something about it.

Mary Wangari Kinuthia, Break Every Chain.

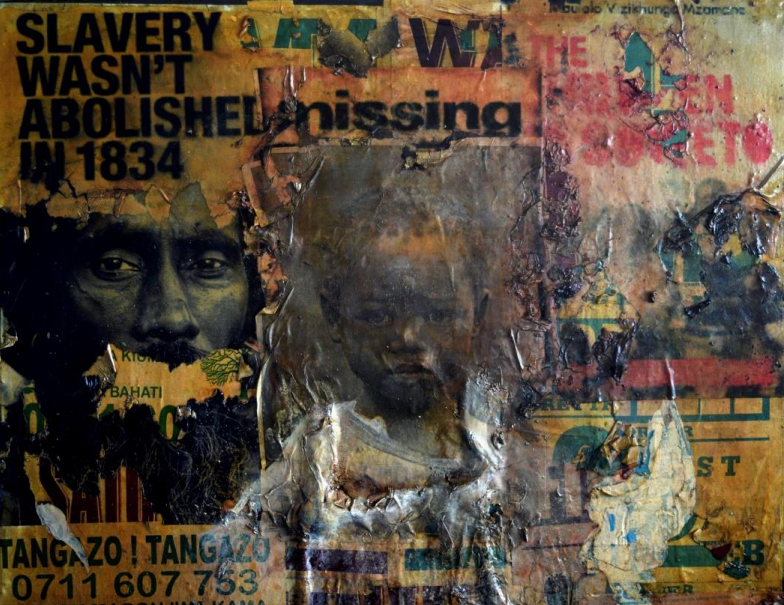

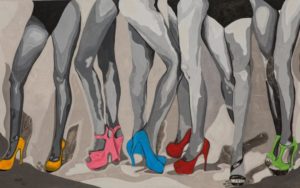

Some artworks in the exhibition rely heavily on the use of symbolism, human form and text to represent slavery or the evils of human trafficking. For instance Nicholas Asao Gaitano’s ‘untitled’ work uses coloured pegs to spell out the word ‘SOLD’ on a piece of painted canvas, perhaps referencing the plight of many young girls in domestic service – with the concept overpowering the aesthetics. Leevens Linyerera’s painting and etching on a brass plate, titled ‘The Medal’, simply depicts three child soldiers. Magdi Adam Suliman created a huge painting on canvas, titled ‘Target’, which seemingly portrays the legs of six women in high heels. The title and imagery suggests that these women have been coerced into sex work, targeted by those out to prey on their vulnerability. Other artists use chains in their work as a metaphor for slavery. For instance Mary Wangari Kinuthia’s work titled ‘Break Every Chain’ bares a pair of boxing gloves chained together at the wrists – the artist states that “the boxing gloves is a way to show that we can fight slavery. The chains represent the slavery…we have to work hard to break those chains”. Samuel Githui’s well executed installation ‘Let Them Go’ (see above) consists of four almost life size figures cut out and trapped between glass. These figures – which appear naked and stripped of all dignity – are further constrained by a padlocked chain which binds them to the column upon which they lean. The use of such symbolism triggers concepts akin to the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade. This may of course be a not so subtle reference to the fact that slavery did not end with its abolition. The artworks discussed above portray different forms of human trafficking through a range of medium and styles. For me however, while they present the viewer with an unequivocal message – those trafficked are sold, they are entrapped and become coerced into undue roles – the artworks offer little in terms of posing news questions, making one think, or shining new perspectives on human trafficking. If one is to go by a recent survey conducted by HAART which states that “In Kenya 83 percent of survey respondents agreed that people in their area know what human trafficking is” (13) then surely one of the roles of an artist, through their artwork, is to articulate and embody another way of seeing, not simply restating what is clear to the mind or plain to see.

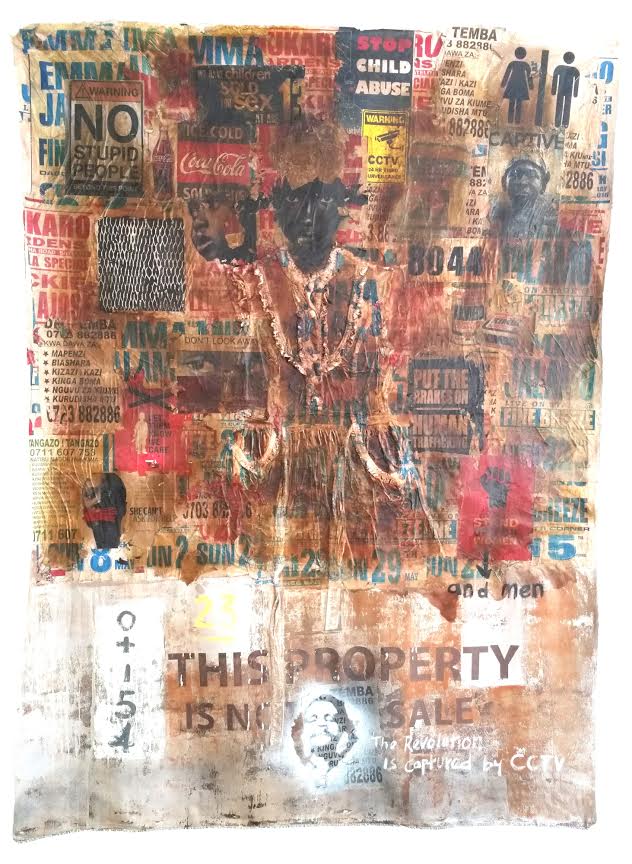

Onyis Martin, Untitled.

A number of works in the exhibition provide this new perspective. For example, Onyis Martin created two mixed media works which use posters – some publicising work opportunities while others advertise products. The image of a young girl is found on one work, a young boy on the other. Onyis states that his work is about consumerism. The boundary between product and person becomes blurred – quite literally as the images of the girl and boy seem to fade into the posters. There is no use of coercion in these pieces – which is true for many who are trafficked. Rather they are often lured by promises of jobs or education.

Ng’endo Mukii, Untitled.

Artist Ng’endo Mukii also deals with this theme, though in a slightly different way and medium – in a series of three photographs which show female figures contorted under the weight and strain of the physical work they are carrying out. Ng’endo states that the idea “was to show the compression of the body…in the way that it removes the individuality of that person and you are completely unable to access this person as a human being, you never see their eyes you never see their face so what you then focus on is the effect it has on their body”.

Onyis Martin, One Day I Will Tell God About You (detail).

Onyis’ and Ng’endo’s work says ‘don’t think this isn’t about you’. Their art presents the often overlooked or dehumanising aspect of human trafficking. It speaks the uncomforting truth that trafficking flourishes in the shadows of our communities. These works also raise questions regarding our capitalist society – a subject seemingly tackled by Brian Omolo whose illustrations depict the black market trade of organ harvesting, or the corrupt and illegal transportation of human beings. Another artist who questions this topic in her work is Mekbib Tadesse Admasu, who highlights the commodification of humans through a photograph depicting a battered and well used parcel, which enwraps a human. We become aware of this by a break in the parcel seal where an arm reaches out. No longer a person, the contents have become a product. Simply put, human trafficking is capitalism at its worst – those trafficked are treated as a commodity: a faceless entity filling a slot, at the mercy of the capitalist, and only looked upon in terms of how much profit the capitalist can make from the worker’s labour. How complicit are we in this cycle, are our actions feeding into human trafficking and modern day slavery?

Brian Omolo, Hidden Cargo.

Other works in the exhibition compassionately tell the stories of those who are trafficked and now stuck in a cycle of abuse and despair. Mohammed Altoum and Humphery Oderowork’s video – which seems to me more like a promotional video for HAART – tells the story of a Kenyan welder who after working in the Middle East is transferred to South Sudan, where he and other foreign workers face daily abuse from their employer. Marc Ellison and Christian Muragura also use narrative – in the form of a comic book. The harrowing illustrations and photography visually tell the story of a 14 year old girl whose father, following local traditions, agrees to her marriage with an older man – physical, emotional and sexual abuse follow. The theme of sexual exploitation is also explored by Gloria Muthoka in her painting titled ‘Not My Own’ – which depicts a female figure with a barcode on her hip, perched on a bed in a darkened room.

For me the strength in these works lie in their ability to enable the viewer to reflect on different aspects of their own life while also building an enhanced sense of empathy towards others. According to Crossick & Kaszynska, art and cultural experiences help to create ‘reflective individuals’, in which one can enhance their understanding of oneself, that can ultimately influence the way we think about issues, such as our current behaviours and practices. (14) In addition, Martha Nussbaum highlights the role of art in extending one’s capacity for empathy. (15) Seeing, or imagining, the world through another person’s perspective can play a crucial role in creating a more just and equal society – one in which citizens learn to respect human rights and do not marginalise or stigmatise others – ultimately, creating a world that is worth living in.

Art as a means to enhance civic engagement and extend the public sphere

Art can create alternative spaces to foster new modes of social interaction. It is in these spaces where the artist, artwork and audience come together. In doing so they foster the circulation of ideas and opinions. This can lead to the mobilisation of people to bring about change in consciousness and society. These activities relate closely to the concept of the ‘public sphere’ which – as discussed by Jürgen Habermas – is an arena which enables deliberation, argument, collaboration and association, where citizens talk critically about common concerns.

The opening night of the exhibition at Shifteye Gallery attracted a huge crowd – estimated to be up to 700, however I feel this number has been exaggerated. Nevertheless this exhibition, and others like it, brings people into a gallery which creates a new form of social space. This social space is continually constructed throughout the exhibition as people come and go – or hold related events such as the discussion ‘what can art do?’ which was attended by over 50 people. Artworks from this exhibition may prompt and trigger thought and questioning which is carried forward into new spaces and with new people. This can be seen as art’s ‘second life’ which is also passed through media – such as newspapers, Facebook and Twitter – reaching a wider public. Given that this exhibition tours Kenya, many people will be exposed to the artwork on show (16) – many people that were perhaps reluctant, or simply not interested, in attending an event purely about discussing human trafficking.

Magdi Adam Suliman, Target.

However, while the artworks may attract numerous people, the audience lacks diversity as it fails to engage with a cross section of society – particularly those who are most vulnerable to human trafficking. Given that the purpose of ‘Art to End Slavery’ is in its name, the project perhaps missed an opportunity by not taking this exhibition into different communities. If additional exhibitions (perhaps open air or street exhibitions) took place within communities (outside the formalities of gallery spaces) I believe this project would have seen even greater public participation and it could have opened up art’s potential to enable individuals or groups to come together, discuss and potentially take action on issues of human trafficking. However, Sophie Otiende did stress that by targeting this exhibition towards Kenya’s middle class it would raise awareness and open a dialogue as to their potential participation in modern day slavery.

Summary

The A2ES exhibition has highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of using visual art in such projects in terms of art’s ability to make one feel more acutely aware of human trafficking in order for us to do something about it. Successful artworks have the ability to instruct or persuade the populace, to give new meanings or perspectives on issues, to provide new knowledge or to build ones capacity in empathy for a certain cause. The use of art can provide a setting in which people can discuss issues, form connections, and potentially take action. Just how much people take away from this experience is difficult to tell. However, according to Sophie Otiende A2ES has raised the profile of HAART considerably – website hits during the exhibition significantly increased, there has been good media coverage, and HAART has been able to reach out to a segment of society that they had otherwise been unable to influence.

On a final note it should be stated that creating work for an exhibition like this can be daunting for an artist – particularly those who are new to such concepts and tasked with creating work of high socio-political significance. Given the number of artworks and participating artist not all works have been mentioned, though while constructive criticisms have been made those artists who took part in this exhibition should be commended for stepping up to this task and not shying away from the role that artists can play in these much needed conversations. Through their medium they provide a refreshing perspective and engage an audience in a new and creative way to speak about these issues – something that would not happen if artists were absent from this dialogue.

Notes:

[1] http://a2es.org/about-a2es/

[2] http://a2es.org/about-a2es/

[3] The United Nations defines “Trafficking in Persons” as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs”

[4] http://www.nation.co.ke/news/Kenya-lands-on-US-human-trafficking-list/1056-2888148-vx2t8b/index.html

[5] http://haartkenya.org/resources/modern-slavery/

[6] The exhibition opened at the Shifteye Gallery on the 30th July and ran until 13th August 2016

[7] http://www.un.org/en/events/humantrafficking/

[8] The exhibition was put together by Rose Jepkorir Kiptum, one of Nairobi’s upcoming curators – though it should be noted that at the time Rose joined the t artists had already been selected and contributed work. Around 34 artists had submitted work and from that 22 artists’ work was chosen to be included in the exhibition.

[9] Pawa254 is a space for creatives who meet, network, share and collaborate on social impact projects designed to foster social change

[10] Ranciere, J (2010) – ‘Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics’, Continuum; Tra edition. pp. 142

[11] Mouffe, C (2013) – ‘Agnostics: Thinking the World Politically’, Verso Books, London pp.97

[12] Jelinek (2013) – ‘This is Not Art: Activism and Other ‘not-art’, I.B.Tauris, London

[13] http://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/kenyahumantraffickingbaselineassessment.pdf

[14] Crossick & Kaszynska (2016) – ‘Understanding the value of arts & culture’, The AHRC Cultural Value Project, Published by Arts and Humanities Research Council. pp. 42

[15] Nussbaum, Martha (2012) – ‘Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities’, Princeton University Press

[16] After the exhibition at the Shifteye Gallery the exhibition moved to the United Nations in Nairobi, after that it travelled to Kisumu and Mombasa

Craig Halliday is pursuing a PhD in the role of visual art in Kenya’s democratisation. Prior to this Craig completed a MA in African Studies, MSc in International Development and has worked and lived in Kenya, Myanmar, Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Zambia. When not working or studying Craig is a keen photographer and has a painting studio in Norwich, UK, where he lives.