“Some gestures and poses are made exclusively in front of a camera. That makes the camera a unique piece of equipment. I think it is very interesting that one is able to see relationships between people take form, or surface when a camera is involved. Furthermore, posing for the camera has a unique history which is highly intertwined with technical concerns. In the past one had to sit still for a long time, due to technical requirements. People nowadays still take similar poses while modern day techniques do not ask for sitting still as long as it used to be.”

Vincent van Velsen in conversation with Sara Blokland.

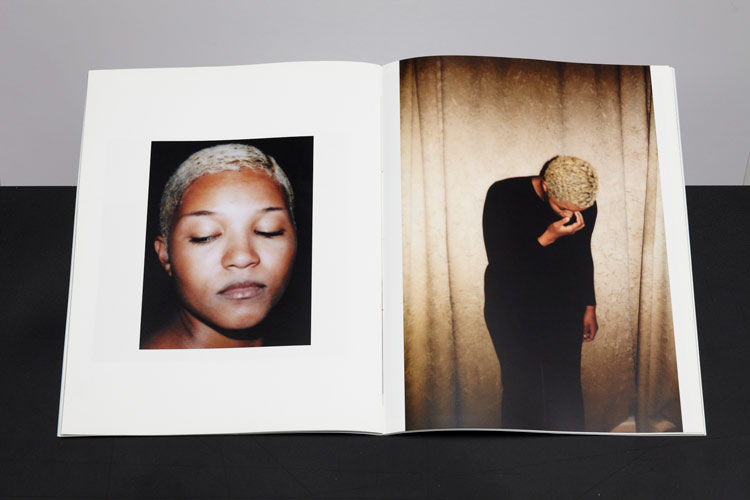

Home, 2004 (detail)

Sara Blokland

About defining base, home and history

Sara Blokland is a visual artist, curator and independant researcher of photography. She lives and works in Amsterdam. Her recent project ‘Srefidensi’, was the reason to have a conversation with her. We ended up talking for hours about much more…..

Photography could be considered the basis of your practice. How do you relate to this medium?

I studied Theatre Design at the Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam. I wanted to become an visual artist and not really a designer. During my studies, painting was an important part of the curriculum and photography I use mainly to photograph the scale models to present the a setdesign as if it was life size. Only in my final year I was really utilizing photography as an autonomous medium. And so I was advized to talk to Willem van Zoetendaal head of the photography department of the Rietveld at the time (1999).

I was not educated as a photographer. However I graduated with photographic works in which I took poses based on classical paintings. These were accompanied by two movies in which I move from one pose to another. After graduation, I went to the Sandberg Instituut [Master of Fine Arts]. Since they did not have photography as an autonomous major there, I enrolled to New Media. At that time I just started to get into photography and was taking a lot of Polaroids. That resulted in the series and publication called ‘FAM’. (2001). The publication was made in cooperation with Willem [van Zoetendaal] who was responsible for the book design.

In 2011 I finished my MA in Film and Photographic Studies (Master at Leiden University supervised by Helen Westgeest and Kitty Zijlmans). The study had a strong focus on the phenomenology of film and photography, which had a big influence on my practice.

FAM, 2001.

Throughout your practice your close family plays an important role. Can you tell something about their involvement?

The polariod series ‘FAM’. was carried out in collaboration with my parents, sister and aunt. They partially also came up with poses for it. These can be seen as kind of performances in front of the camera. The depicted situations seem as if they are private, but actually never occurred in our real life. It was touching on boundaries: how far they were willing to go. For me this was a very successful project, including the modes of presenting the work.

Some gestures and poses are made exclusively in front of a camera. That makes the camera a unique piece of equipment. I find it is very interesting that one is able to see relationships emerge when you start to take pictures of people.Furthermore, posing for the camera has a unique history which is highly intertwined with technical concerns. In the past one had to sit still for a long time, due to technical requirements. People nowadays still take similar poses while modern day techniques do not ask for sitting still as long as it used to be. What I find interesting here, is what happens with people the moment they are photographed. I consider it often a form of experiment the way people are acting at that moment and time. It is a moment of performance. And if you [the photographer] work with people you knowvery well, something else happens than when you work with s atranger. It creates a whole different situation.

Linda, 2006.

The series ‘Linda’ (2006) is a project about my sister. It deals with representation. The ways others as well as myself have photographed her over time (1990-2006). The pictures on show are presented as a sequence starting from the most naive gaze, ending with the least naive look – not based on chronology. The work ‘Father’s Paradise’ (2006) is consisting of photographs my father took of his garden. It tells something about the place where you live. And about the aesthetics you desire. You look at his ideal and the outcome of its realization. Only once, he is present himself, right in the middle. On a photograph my mother took.

Father’s Paradise, 2006.

Surroundings and the construction of a home – both physically and conceptually – and the malleability thereof, is present in several of your projects.

‘Home’ (2006) is an installation that I made in the Bijlmer [Amsterdam South-East]. It partially consists of pictures from the Municipal Archives. Pictures that were made as complaints for example when there was mildew in a house. The installation also includes pictures that I took of three families and mainly their interior. And then the archival footage interspersed with movies. I aimed to combine those different elements in one installation. In order to define one’s base, one’s home, and one’s history. Not in a cultural sense, dealing with dance, music, art or stuff like that, but concerning simple aspects such as a view from a window. Or rather, the physical structures of a house, the architecture of a home. The surroundings in which one grows up and feel safe at. This could be in the Bijlmer, in a home or architectural environment that most people experience as unpleasant. Still, such places are able to be a pleasant reminder of one’s childhood. Such subjectivity, for example, with the Ajax-carpeting stretches beyond any aesthetical preference and merely becomes a cultural memory. The objects that people put on their wall, I intentionally photographed in such way that they become autonomous items within their surroundings. On those objects I focused. I purposefully framed the pictures in such way that it seems like the viewer’s gaze is scanning the room. You look around and what you see is this.

They are very specific objects.

Definitely. The objects concerned are most of the time put on the wall as a physical carrier of a specific memory. As objects they have no other purpose than to remind one of that memory.

Reproduction of Family, 2007.

The positioning of objects, relationships and modes of presentation also play a major role in other projects, such as ‘Reproduction of Family’, part 1 (2007).

That project is very much about the representation of objects. On the one hand, when you see an object in the Tropenmuseum showing a face, or you see objects in which faces are present, these signify people who represent a general idea of ‘people’. It’s (in most cases) not about an individual person, it’s not about who this is person exactly. With these types of displays you can clearly derive the times the goal is to present a specific individual – just by the way these are presented to an audiance. And most of the time the latter concerns in that contxt The Westerner. I was interested to see what happens when I would present my own family as such objectified items, and what happens to a portrait when the image is present on a utensil. In this case it concerns ceramics; objects which I made with the assistance of ceramist Bastienne Kramer. The issue was how to relate to the interaction between near-decorative faces and an obvious colonial history. Furthermore, I incorporated content from books that I collected in serious amounts. These were from the 70’s and concerned tropical plants and how you need to take care of them in a European context, plus cookbooks with novel exotic dishes aimed at a Western audience.

To get back to the influence of your MA Film and Photographic Studies. What was it’s impact on your interaction with the medium? As I see several changes emerge in your works during the period you studied. For example, in the ‘Unfixed’ project. The subject matter changed from dealing with issues relating to close family towards larger, more general topics. Before, your family functioned as a starting point to tell a larger story and discuss relationships. During and after your studies, for example the presence of post-coloniality became more explicit.

I think the transition began around 2008, with the film ‘Brother’. Before, I focussed on the medium photography in itself, through working with my family and the way the medium related to modes of displaying an image. How does such a method affect the manner in which you see and relate to a picture, interpret it? For example, the pixelation and the way it was photographed. It comes with a certain implicit perception. I think the major change for me – partially influenced by Susan Meiselas – is that I went from mere imagery towards stories via images. Thus literally, explicitly telling them. Now, I generally employ sound and text. Previously those elements were not part of the work at all. ‘FAM’. consisted of pictures solely, and really dealt with the depicted image – no text involved. From ‘Brother’ onwards the works have included stories without exception.

Mother’s History, 2014.

As for example with ‘Mother’s History – A Library of Language’ (2014), presented at the Stedelijk [Museum Amsterdam, ‘On the Move’, 2014] is a story, also about my family. In it I explore my mother’s Amsterdam-Jewish family history and in the film she speaks about her identity, idealism and memories of her post-war childhood. For me it is an investigation of her (Jewish) identity and (the impossibility of) visualizing trauma. She tells a story about her generation. And about her fear of being recognized as a minority. In other earlier works I emphasized postcolonial history and it’s visual representation. And to elaborate on the presence of text: on all the pictures there is a description, printed over the images. It takes it a step further. For example, on a photo that my mother held of her trip to Israel, there is a sentence that states what she said at the specific moment [when she held that picture]. And it also tells what the picture shows, when and how it is made. It is a kind of documentation of that moment when she saw the picture again, and it is information, as a kind of watermark. Plus the pictures are all re-photographed with flash. Thus you can actually see the light source from outside of the original image, in the image. This makes the viewer aware of the fact that it’s a reproduction.

Unfixed, 2012.

And can you tell something about the project that you did as a curator: ‘Unfixed. Photography and Postcolonial Perspectives in Contemporary Art’ (2009) of which a book was published in 2012 [in collaboration with researcher and curator Asmara Pelupessy].

The multimedia project ‘Unfixed’ actually concerned a form of protest. It entailed a way in which individual artists not only are able to respond to history but also take a new position in relation to it. Hank Willis Thomas is a great example of such an artist. Hank deals with themes like identity and popular culture. For example, he uses advertisement and then adapts them in such way that the ‘real’ image is left. So he kind of uncovers a sometimes shocking reality which was already present in the original source. He put afront a message that very much differed from that of Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, a Native American artist. To show this difference was our intention exactly. To address the diversity within diversity; because often all diversity is considered as being one and the same thing. The intensely different viewpoints of Hank Willis Thomas and Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie exemplified the size of the gap between various modes of thinking between distinct minority groups, even as they are part of the same society. This exactly entails the message we wanted to convey to the Dutch public: different viewpoints exist among individual people. This is not just applicable on the differences between ‘the us’ and ‘the other’, but also among ‘the others’. In the English context there is Black British, and then there is African-American. This difference in terminology already signifies a variation. And such variety becomes even more evident when you look at a British society that is way more focused on classes and socio-economic backgrounds, while the U.S. is mainly concerned with [ethnic] origins.

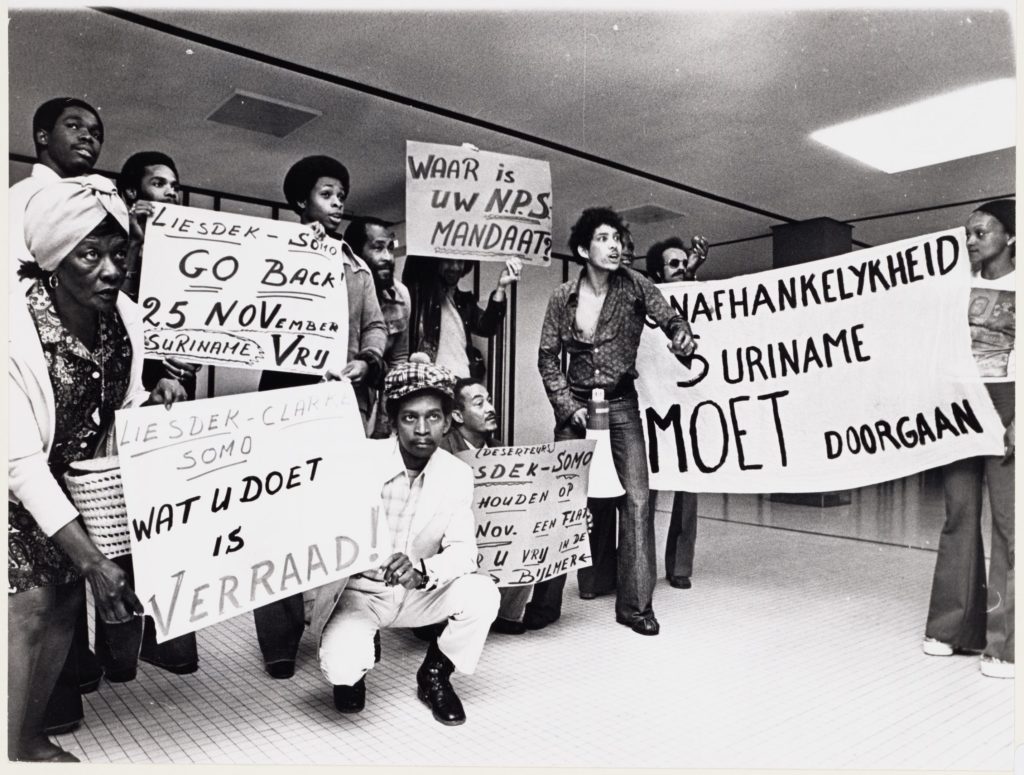

Srefidensi, 2016.

And you took the protest aspect along with you to your current research: ‘Srefidensi’, which carries the undertitle: ‘A photographic perspective on the Surinamese histories of resistance and emancipation’. What does this project entail?

‘Srefidensi’ [independence for Surinam from the Netherlands on November 25, 1975] is a broader collaborative project with FOTODOK [Utrecht, NL]. It’s aim is to investigate the ways in which one can observe resistance and emancipation through photography, specifically dealing with Surinam before 1975. Not necessarily the period directly leading up to the independence, but more so before that time. The subject is approached by means of a number of case studies. The project at CBK [Amsterdam] concerns the case study ‘Srefidensi and the flag’. Another part is ‘the march of indigenous people’ which was photographed by Cary Markerink in 1976. I think a fairly unknown event to most people. It was a march of four days in which the indigenous ‘people of Suriname’ raised attention for their fundamental rights that were violated instantaneously when the independence was effectuated. Other studies are the formal dress of the granman [maroon chief] and the many self-commissioned photographs that were taken from resistance hero Wim Bos Verschuur that contain extensive symbolic elements. And we focus on texts and signs that were carried during demonstrations throughout Surinam and the Netherlands, relating to independence.

And how does the CBK [Amsterdam Zuid-Oost] project fit into it?

It is one part of the Srefidensi photo project. CBK wanted to work together and we decided to create a work in public space. Aforehand I had already asked Jaya Pelupessy to cooperate with me on the project. It is a billboard on which we will over the next five months periodically apply a new visual layer to. We started out with the image of [the Statue of former Queen] Wilhelmina, because it was taken down and removed from the same place the flag [of Surinam] was hoisted. A similar act of hoisting happened in the Amsterdam Bijlmer [where CBK Zuidoost is located]. And then there is the discussion about the flag itself. I spoke with the head of the [former] flag committee and filmmaker Afra Jonker travelled to Suriname to talk with Jack Pinas – who unfortunately deceased recently – for me. He is the designer of the official winning design for the flag which bears close to no similarities with the eventual and executed flag. Previously, there was the statuary flag with the circle (1959-1975). That’s the flag of Surinam when the country was still semi-independent; which was designed in the 50’s by Noni Lichtveld, the daughter of writer and designer [Lou Lichtveld, alias writer Albert Helman]. Many people oppose that flag, because the design symbolically allocates each individual star and it’s color to an ethnicity present in society. For example, yellow stands for the Chinese population and red for the indigenous natives. In 1975, a design competition was held. It was won by Jack Pinas, but his winning design was utterly changed by the flag committee; and through my research I learned that at the time the flag expert from the United States Witney Smith was in Suriname around. He is also the designer of the flag of [neighboring country] Guyana. Smith was in Suriname to make a book about the history of the Surinamese flag and to witness the birth of the new flag. He collected a lot of material, and also gave advice. For example he recommended to change the white star into a yellow star, as the white star would not be properly visible in the tropical light. So it happened. I requested for the archive of this expert in Texas to look into. It turned out that he made a lot of designs, which raises questions on the way Jack Pinas’ design was dealt with. These designs, amongst which Witney Smith’s, we have now put on the billboard. What I find striking here, in the course of such historical research, is actually the idea of representation of a people. Some designs for the flag for example, were more political party related flags. And then I am interested in what ultimately gives form to a national identity and in what way can a country be represented. And who has the final say about a design – and more of such questions.

Srefidensi, 2016.

How does this research still relate to photography, or visual culture?

It is about the different ways you can actually use photography to look at forms of resistance. So it is not so much whether you have a story in mind about resistance and then go look for pictures to illustrate it – I am not interested in that. I aim to see if with photography itself, with for instance the images of the statue of Wilhelmina and the way this statue is depicted, if you can tell a story with those images to say something about those moments and the way there has been photographed and how it relates to history and it’s [changing] power dynamics. Images themselves seem irrelevant. But the connection of a certain perspective present in an image is relevant. Then, the story can ensue from that perspective. So, with my research into the [statue of] Queen Wilhelmina one could consider it as individual images from a certain moment in time. However when you look at who is depicted next to the statue and in the research you emphasize the conscious construction of an image, you can tell a story about the colonial power relations. Such an image of the statue of Queen Wilhelmina is interesting because you can find pictures from the studio in The Hague, where it’s maker poses next to the statue. And from that moment on you can follow the history of the statue, with all sorts of people transporting, adoring or displacing it; all in the context of a colonial history. All different connections with the statue are come about. The workers sit on top of the transportation crate while below them; the white men in white uniforms are posing in front of it. And you see Surinamese people taking down the statue just before independence day in 1975. It is highly interesting to take notice of which exact moments were documented; serving what purpose; and how you can derive power relations from those images? During the ceremony of the statue’s relocation at Fort Zeelandia you can observe a totally different power relation towards the statue. This is done deliberately. The powerfull influence of photojournalists at the time is often underestimated. These pictures are all very consciously staged, while taking into account: who is important and what is the relation to the statue; who is allowed to be in the picture; and where are they positioned in relation to the statue; and who are they? From these images you can derive and determine the power relations regarding the statue and thereby the Dutch colony. I visited different archives to find images [photographs] and see the [changing] colonial relationships. Those are the things I study. The presentation at CBK is the first outcome.

And what will be the final outcome of the entire project?

Concerning the whole project: a publication in a newspaper format will be produced in collaboration with graphic designer Yvonne Versendaal [who also designed the website of the project] and the stories will become part of an autonomous film, which I am currently working on. This film will include the five narratives [case studies], or directly or literally, but I am also not 100% sure yet how they altogether will be exactly featured. At the moment I am in the middle of this extensive and crucial part of the process and it’s considerations. Conclusively in March or April I will organize a public event to screen the film, in close consultation with Wayne Modest [Head of the Research Center for Material Culture, which is part of the National Museum of World Cultures]. Plus there is the website that step by step will be enriched with content. The goal is to present the research and stories relating to ‘Srefidensi’ – within the framework of the distinct topics of protest, symbolism and imagination – and to continue with adding content to the website for years to come.