Julius Bloch: Portrait of the Artist

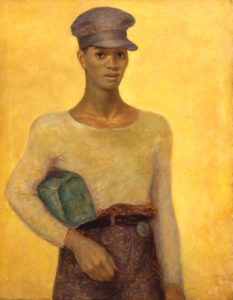

Street Metal Worker, 1940s.

About:

Julius Bloch (1888-1966) had a natural empathy for working people, whom he captured in moving portraits. He approached the subject of a stevedore, a prisoner, a factory worker, or a dispossessed farmer with the dignity and formality usually reserved for commissioned portraits. The financial hardships of Bloch’s own family–German Jews who emigrated to Philadelphia in 1893–made him attentive to the emotional burdens of the Depression, its crushing effect on the morale of the average person.

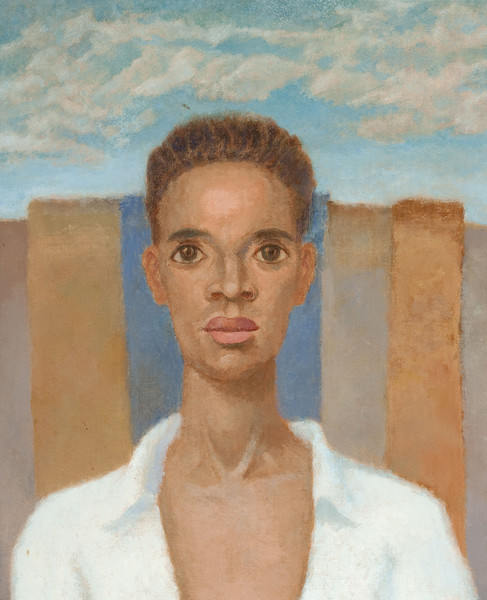

City Dweller, undated.

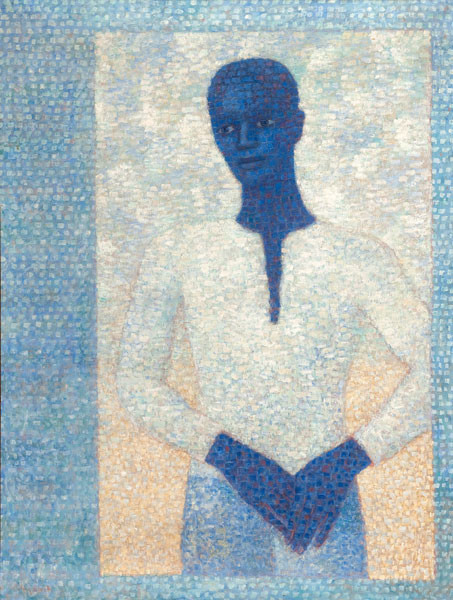

Horace Pippin, 1943.

Man at open window, 1957.

Bloch lived with his family on Uber Street in North Philadelphia for most of his life. He trained at the Pennsylvania Museum and School and later at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he was greatly influenced by the legacy of Thomas Eakins.

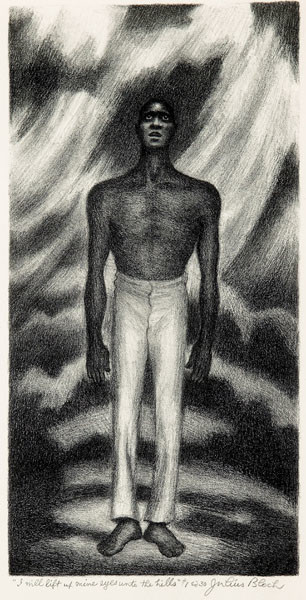

Though the onset of the Depression seemed to Bloch and his contemporaries to signal the death of American culture, the 1930s would prove to be a stimulating, generative period in American art. By the end of the decade, Julius Bloch would be transformed from an unknown Philadelphia painter to a social realist with a national reputation.

Bloch’s compassionate identification with the suffering of innocent people naturally drew him to the Black community, which was faced with racial discrimination as well as economic privations. Powerful images of lynching in his work of the 1930s were followed by sympathetic portraits of Black community leaders and artists such as Horace Pippin.

Will Lift Up Mine Eyes to the Hill, undated.

Approximately forty paintings, drawings, and prints survey the range of the artist’s career from 1912 to the early 1950s. Works owned by this Museum are supplemented by loans from other institutions and private collections, most notably that of Benjamin D. Bernstein, whose friendship for Bloch and his family has ensured the preservation of his work and archives. A special issue of the Museum Bulletin written by Patricia Likos accompanies the exhibition, which is supported in part by a grant from The Pew Memorial Trust.