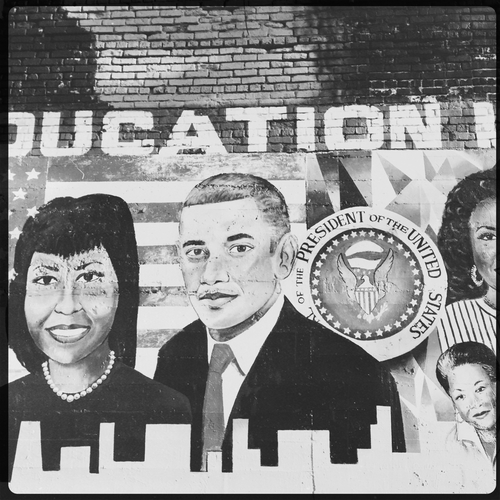

A view of a community mural, at the Donnelley Center Community Art Garden, a neighborhood art playground. Migrants moving to Chicago all tended to congregate in the same region. This region on the South side of Chicago was located in the Douglas and Grand Boulevard community areas. The region was so defined that even crossing the street could mean entering into a completely different world. Chicago's Bronzeville is home to such famous names as Louis Armstrong, Jazz legend; Ida B. Wells, civil rights leader; and Lorraine Hansberry, author of A Raisin in the Sun. Furthermore, Bronzeville is said to get its name from James J. Gentry who so named it because of the skin color of the predominant African Americans residing in the area. Most migrants, including women and girls found themselves living in Bronzeville; whether it was in their own kitchenettes or in homes designed to help the suffering.

Carlos Javier Ortiz (born in San Juan, Puerto Rico)

All photos from A Thousand Midnight Series.

About:

Carlos Javier is a director, cinematographer and documentary photographer who focuses on urban life, gun violence, racism, poverty and marginalized communities. In 2016, Carlos received a Guggenheim Fellowship for film/video. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally in a variety of venues including the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts; the International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, NY; the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago; the Detroit Institute of Arts; and the Library of Congress.

In addition, his photos were used to illustrate Ta-Nehisi Coates’ The Case for Reparations (2014) article, which was the bestselling issue in the history of the Atlantic Magazine. His photos have also been published in The New Yorker, Mother Jones, among many others. He is represented by the Karen Jenkins-Johnson Gallery in San Francisco.

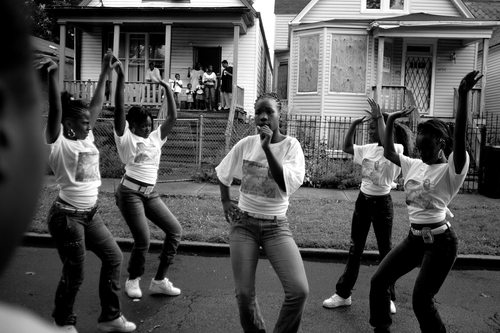

Girls in the Englewood neighborhood on ChicagoÕs South Side attend a block party to celebrate the lives of Starkeisha Reed, 14, and Siretha White, 10. Starkeisha and Siretha were killed days apart in March 2006. The girls’ mothers were friends, and both grew up on Honore Street, where the celebration took place. Englewood, Chicago, 2007

His film, We All We Got, uses images and sounds to convey a community’s deep sense of loss and resilience in the face of gun violence. We All We Got has been screened at the Tribeca Film Festival, Los Angeles International Film Festival, St. Louis International Film Festival, CURRENTS Santa Fe International New Media Festival, and the Athens International Film + Video Festival.

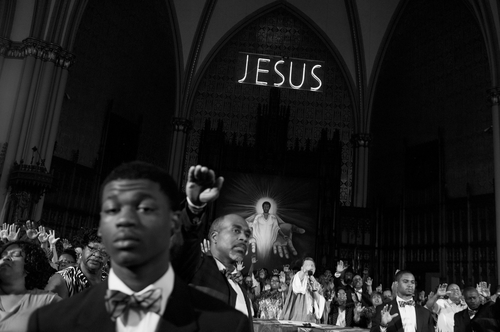

Members of St. Sabina Church pray to end violence in Chicago. More than 50 young people have been murdered in the neighborhood since 2006. Auburn Gresham, Chicago, 2013

Carlos’ current project is series of short films chronicling the contemporary stories of Black Americans who came to the North during the Great Migration. Beginning with his mother-in-law’s story, Carlos is exploring the legacy of the Great Migration a century after it began. For Carlos, who moved back and forth between Puerto Rico and the U.S. mainland as a child, the story of a displaced people in search of stability and economic opportunity resonates with his own.

Flowers placed on Emmett Till gravesite at Burr Oak Cemetery in Aslip, Illinois. Emmett Till was an African-American boy who was murdered in Mississippi at the age of 14 after reportedly flirting with a white woman. Till was from Chicago, Illinois, visiting his relatives in Money, Mississippi, in the Mississippi Delta region, when he spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the married proprietor of a small grocery store there. Several nights later, Bryant’s husband Roy and his half-brother J. W. Milam arrived at Till’s great-uncle’s house where they took Till, transported him to a barn, beat him and gouged out one of his eyes, before shooting him through the head and disposing of his body in the Tallahatchie River, weighting it with a 70-pound cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. His body was discovered and retrieved from the river three days later.

Carlos’ work has been supported by many organizations including: the University of Chicago Black Metropolis Research Consortium Short-term Fellowship (2015); the Economic Hardship Reporting Project (2015); the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting (2013); the California Endowment National Health Journalism Fellowship (2012); the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation (2011); Open Society Institute Audience Engagement Grant (2011); and the Illinois Arts Council Artist Fellowship Award (2011).

From liquor stores to churches murals of President Obama and other famous African American icons live on walls in Chicago.

In addition to his photography and film, Carlos Javier has taught at Northwestern University and the University of California, Berkeley. He lives in Chicago and Oakland with his wife and frequent collaborator, Tina K. Sacks, a professor of social welfare at the University of California, Berkeley.(copyright, text and courtesy: the photographer)