Ephrem Solomon set out to introduce me to the group of artists he grew up with and who, like him, use their art as a platform for social commentary. I return home grateful and fulfilled; the visits I have made with him have brought me closer to the heart of modern Ethiopia.

Rosalie van Deursen gives the floor to Ephrem Solomon.

Ephrem Solomon’s Choice: studio visits to Ethiopian artists

Featuring: Kirubel Melke, Tewodros Bekele and Dereje Shiferaw

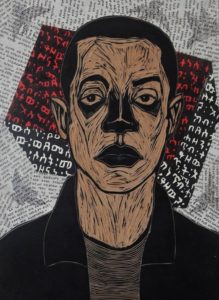

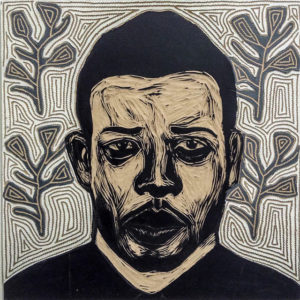

One of my favourite artists is the Ethiopian, Ephrem Solomon. I have been lucky enough to meet him several times and met him again in December 2016 in Addis Ababa. During a visit to his studio he showed me his latest work and as usual for such a prolific artist he has been working around the clock, producing an amazing amount of art, work in progress and experiments. He mainly expresses himself through woodcuts and mixed media, for example by gluing text from Ethiopian magazines and newspapers or his own personal thoughts, to his woodcuts. He depicts the daily life of ordinary Ethiopians and the issues they face. These portraits show facial expressions that leave no doubt about the subject’s state of mind. In some works Ephrem calls openly for more equality whilst in others he depicts people as machine-like figures. Taken together, his work shows a rich reflection of the complexities of the current social, economic and political situation in his country.

Ephrem Solomon studio.

Ephrem Solomon, Work in progress/ Ephrem Solomon, Untitled (Folk Memory Series), 2014.

During my December 2016 visit Ephrem was eager to show me work by other Addis Ababa artists. Together we visited the studios of other socially engaged artists: Kirubel Melke, Tewodros Bekele and Dereje Shiferaw. Ephrem explains: “I find it interesting how we all grew up together and how we all experience the same situations but reflect in a different way. Through art we tell what we experience as the truth. We live because we have hope in the future. By looking at all our work you can read and understand the current zeitgeist.”

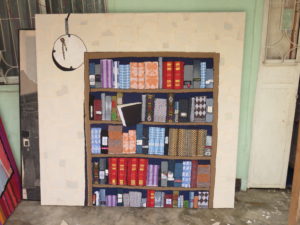

Kirubel Melke, Book Case, 2016.

Kirubel Melke, Book Case (detail), 2016.

Kirubel Melke’s mother worked in a garment factory, which meant he grew up experimenting with textiles. Nowadays he creates large collages with scraps of textile many of which show narratives and some of which are abstract. Kirubel’s art is a statement on Ethiopian society but also on larger global issues. One of his works shows a giant bookcase. He explains: “A bookcase seems ordinary but books represent people and different books represent different ideas. As you can see, only one book is sticking out of this bookcase. At this moment that’s the only available book in Ethiopia; the other books are silent.”

There are also fashion labels in his bookcase, sewn on with big stiches. Kirubel: “The labels represent globalization. It makes us forget where we come from and what our traditions are. It doesn’t worry me that it happens but it does worry me that we don’t question its results. Everything looks the same nowadays and everything is about money; the clothes people wear represent personal and social status. That’s also why I chose to use big stitches because poor people in this country sew their own clothes.”

In a lot of his work he uses white cloth known as netela for the background. It’s a symbolic fabric used for traditional clothing, worn on special occasions such as church ceremonies. Kirubel wants to highlight the contemporary contrast between tradition and modernity and record such observations for future generations.

Kirubel Melke with giant piece with pedestal in Addis Ababa (Kirubel in his garden).

Detail pedestal in Addis Ababa

His latest work is gigantic. It shows a pedestal crowded with figures, some of whom wear medals, as well as a student hanging from a noose. The scene is set above Addis Ababa, recognizable by its yellow and green construction fences, subway line and signs in Chinese. It is a clear reference to the student protests of last autumn. He chose this particular pedestal which connoisseurs of the city will recognize immediately as the monument to fallen martyrs. Kirubel explains: “The first martyrs fell in the combat against the Italians in 1937 and the second today.”

Kirubel Melke, False Fruit (details), 2016.

In a work entitled ‘False Fruit’ two figures are depicted standing next to a big TV screen showing people talking through a microphone. Kirubel explains: “On TV people speak about Ethiopia and its development but reality is often different. ‘Fruit’ doesn’t come from Ethiopia but from China, the United Arab Emirates and other places in the world”. Kirubel concludes: “I am the spokesman of my generation; I need to ensure that the next generation will not forget what happened.”

From Kirubel’s garden we drive to the Mercato slum; Africa’s biggest market where practically anything can be found. Some people refer to it as a big pile of junk whilst others swear it houses hidden treasures. Artist Tewodros Bekele was born and raised here. Entering his small studio, which doubles as his house, is a fascinating experience. Next to it he has built a giant treehouse from junk and together we climb up and enjoy the beautiful view over Mercato. Tewodros explains that he frequently climbs into his watchtower to meditate and clear his head. He has built it little by little and says he feels like a kid, never too old for an adventure!

Tewedros Bekele in his Treehouse overlooking Mercato.

Tewodros Bekele mainly works with junk that he recycles as a direct expression of his concern about the current state of the planet and in particular global warming. One of his artworks consists of a piece of canvas made with the cloth that people traditionally used to cover their dusty kitchen ceilings. It’s burnt because many people cook inside on open charcoal fires and the hole is sewed together with green stitches. The needle is still visible on the surface. Tewodros: “I want people to think about the hole in the ozone layer, so they start to repair nature. We need to plant trees and grow grass.” In ‘City Scape’ (2016) the hole in the ozone layer is again visible. This time he has packed his message in the shape of a cityscape built from a PC motherboard and an oil drum.

Tewodros Bekele, Ozone, 2012.

Tewodros Bekele, City Scape, 2016.

Having lived all his life in the Mercato neighbourhood, Tewodros has always been surrounded by junk and it became a source of inspiration. Recently he has started working with plastic water bottles that he burns into human figures. “I change the plastic skin. When you burn plastic you don’t know which shape you’ll get. I like the idea of using water bottles because they represent life and survival. By burning them I create different human shapes. A lot of them are disabled. The unexpected aspect of the burning process is just like human life, because we don’t know when we are young how we will physically change when we get older. It’s something to think about because nothing is steady in life. You think you have control and follow your own path but – and this is the case in Ethiopia- we are just a small cog in the big picture and there are a lot of limits.”

Tewodros Bekele, Disabled People, (series), 2016.

Ephrem Solomon loves Tewodros Bekele’s work and studio. When Ephrem and I are together in the treehouse he sighs: “According to our standards Tewodros lives in a poor place and a lot of people are scared of such slums, but to me it represents freedom. I find it beautiful to see how we all get influenced by the context or society we live in. Tewodros is a product of Mercato, he is surrounded by trash and it has made him who he is and influenced how he perceives life and creates art.”

Ephrem & Tewodros in conversation

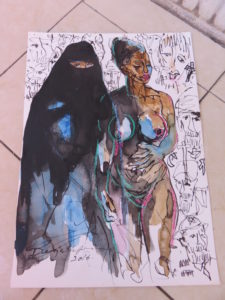

We leave Tewodros Bekele’s studio in Mercato to drive to another part of the city to meet Dereje Shiferaw. While we are in the car Ephrem explains why Dereje’s work is important: “He shows daily life, not just of Addis Ababa, but of the whole country. In a quick, sketchy way Dereje shows us the history of the country by depicting its people. He is not pretentious, lives a simple life and has a lot of positive energy.”

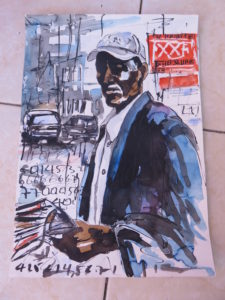

When we arrive at Dereje Shiferaw’s house he immediately shows us a thick pile of watercolor portraits that he has made all over the country. He paints people performing their daily activities in a couple of lines, forms and asymmetric shapes. Dereje: “Sometimes I distort things but mainly I use organic forms because human beings are nature and that’s what I believe in. If you want to study art, you have to study nature. Lines, compositions, colours, rhythms all these principles of nature are principles of life and therefore art.”

Dereje showing his works outside his house

The watercolors Dereje makes of Addis Ababa show the signs of rapidly changing society; Chinese signs and ubiquitous construction sites. They also show how people dress these days in Ethiopia, from modern Western styles to niqabs, veils covering the whole face apart from the eyes. Dereje laughs when he explains about the Chinese taking over Ethiopia: “We Ethiopians are famous for our handmade clay coffee pots that we use during Ethiopian coffee ceremonies and you won’t believe it but there is a shiny Chinese ceramic mass produced version nowadays! I laugh but it’s sad, we are losing our traditions and with them our wisdom.”

Dereje Shiferaw’s water colors, 2016.

Ephrem Solomon set out to introduce me to the group of artists he grew up with and who, like him, use their art as a platform for social commentary. I return home grateful and fulfilled; the visits I have made with him have brought me closer to the heart of modern Ethiopia.

Rosalie van Deursen, Art Historian

www.urbanafricans.com & www.rosalievandeursen.nl

Text edited by Philippa Collin

See also: https://africanah.org/?s=kirubel+melke

See also: https://africanah.org/ephrem-solomon-life-vs-time/

See also: https://africanah.org/dereje-shiferaw-2016-ethiopia/