Bikoro’s visual practice is, in fact, an organic and consequential research of modes of remembering, recollecting, rewriting, rethinking and reshaping histories and temporalities. Each performative gesture, each written or spoken word, installation or moving image taking part into the artist’s polyhedral research, is just a segment of a dense apparatus of references and correspondences.

Chiara Cartuccia on Nathalie Mba Bikoro

Future Monuments: Re-inventing the Human Memorial, 2014, courtesy the artist

Nathalie Mba Bikoro: Nothing is Lost to History

Is this boat sailing into eternity toward the edges of a nonworld that no ancestor will haunt? [1]

– Édouard Glissant

In a passage of his book Poetics of Relation, Martinique author and thinker Édouard Glissant depicts the highly poetic, yet dreadful image of a slave-ship sailing from the coasts of West Africa, into the unknown of the Atlantic Ocean. The writer describes the vastness of the sea, opening up in the eyes of those men and women deported from their native lands, forced towards a nonworld, a distant and abstract harbour that the spirits of their ancestors won’t be able to reach. Glissant refers to the original loss of collective memories, suffered by the descendants of the enslaved Africans, who now constitute the populations of the Caribbean. The author pushes his thoughts a little further, stating that it is precisely this absence of historical awareness, this externally imposed negation of personal and collective histories, which makes the weight of history so heavy and its presence (in the absence) so obvious. Still, even though traditions and familiar memories have been eradicated, in the brutality of the Middle Passage and in centuries of slavery, something remains. Something survives, silent, unnoticed, in the very fabric of present time.

As a writer, Glissant declares the moral necessity of recovering this subterranean memory of lost pasts, in order to define its continuity within the present:

The past, to which we were subjected, which has not yet emerged as history for us, is however, obsessively present. The duty of the writer is to explore this obsession, to show its relevance in a continuous fashion to the immediate present. This exploration is therefore related neither to a schematic chronology nor to a nostalgic lament. It leads to the identification of a painful notion of time and its full projection forward into the future, without the help of those plateaus in time from which the West has benefited, without the help of that collective density that is the primary value of an ancestral cultural heartland. That is what I call a prophetic vision of the past. [2]

Where history is denied, the act of remembering becomes imperative. The displacement of African people during pre-colonial slave trade, the migrations taking place after the colonisation of the continent –and continuing in contemporary, post-colonial times– the systematic process of reconfiguration of traditions, religions, languages and habits operated by colonial powers, the genocides of peoples, all of this contributes to consume and corrode cultural believes and personal memories. Where there is oblivion and negation, where forgetting is a kinder task than remembering, there to perform a legacy, to bear a distant witness, becomes essential. This because, as Glissant writes, the act of commemoration doesn’t influence only our understanding of the past, it also shapes the present as well as the future. We can face the past while looking ahead, and grasp the shades of future in the ancient stories of our ancestors. There is no chronological organisation –nor classification– each movement we make acts on all the possible configurations of time(s). Thus, we could maybe state that a politically charged gesture is able to affect all the levels of the possible. This type of historically conscious approach gives body and reason to Nathalie Mba Bikoro’s artistic work.

Bikoro’s visual practice is, in fact, an organic and consequential research of modes of remembering, recollecting, rewriting, rethinking and reshaping histories and temporalities. Each performative gesture, each written or spoken word, installation or moving image taking part into the artist’s polyhedral research, is just a segment of a dense apparatus of references and correspondences. Since early 2000s, Bikoro is developing an open conversation, involving communities, fellow artists, researchers, and anyone interested in walking part of this artistic path with her. In the context of this essay, I will discuss some of the conceptual issues and artistic images presented in Bikoro’s practice, reading some of her most recent artworks as partial manifestation of a wider theoretical discourse.

Strategies of embodiment

Nathalie Bikoro is first and foremost a performance artist; even when she uses materials other that her own body, she always shows a sharp performative approach. All the works of this artist are defined by action and talk through, or of, the body. Bikoro understands the necessity to be present and active in the immediacy of present moment, in order to be politically relevant and have an effect on reality. The body is the place where temporalities interweave, the favoured stage for negotiation, negation and affirmation of pasts and futures. Bikoro proclaims the intrinsic historicity of the body, as a crucible of simultaneous temporalities, a bearer of the past and forgotten as much as of the yet-to-come. For this reason, in her artistic struggle against cultural amnesia and historical negation –a struggle that Glissant would have defined a poetic endeavour[3]– Bikoro searches for strategies able to reveal again the proximity of undermined memories and lost narratives to the body.

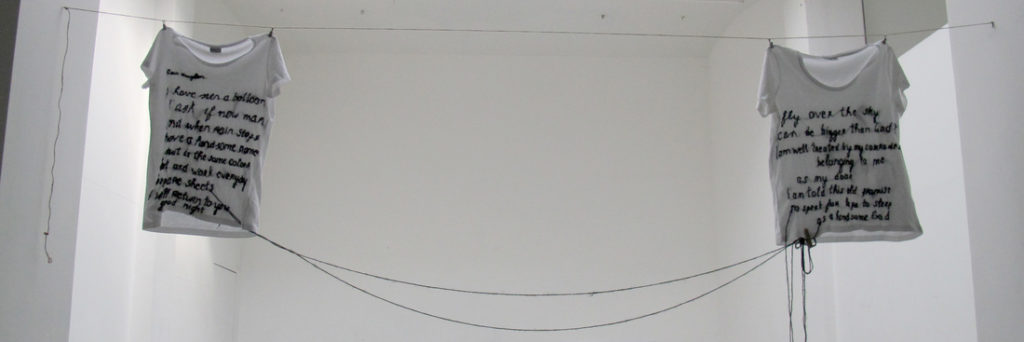

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Future Monuments: Re-inventing the Human Memorial, 2014, courtesy of the artist

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Future Monuments: Re-inventing the Human Memorial, 2014, courtesy of the artist

Future Monuments: Re-inventing the Human Memorial is a long-term, on-going project, composed by eleven distinct artistic interventions, each one responding to the cultural specificities of the location where it takes place. The first intervention, Future Monuments: Forbidden Histories, has been produced in Berlin, and it consists in a series of photographic portraits of men and women, descendant of African people who were incarcerated in German concentration and extermination camps during the two World Wars, or who have been victims of genocides. On the arm of each of the portrayed individuals is sewed a Star of David, made out of African wax fabric. This star encloses a double appropriation as well as a cultural lie. While the religious symbol of the Star of David has been shamefully used during Nazi Germany to literally ‘label’ Jewish people, the African fabric, indeed originally from the Netherlands, is actually just a gift made by European powers to African countries in the 1960s, to congratulate for the independences recently conquered. The wax fabric becomes here the symbol of a second wave of colonisation, the one perpetuated using political and economical power, able to invent traditions and deface history. This work deals with the long lost memory of atrocities perpetuated by Germany in the course of its colonial past. The purpose of the artist is to erect a living memorial, since an official one, made of stone or bronze, or of written words on schoolbooks, is lacking. Bikoro depicts the protagonists of Future Monuments as physical manifestations of an extreme resistance to negation: they not only confront the cultural and historical amnesia, they embody the lacuna itself.

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Planting Present Tense, 2015, courtesy of the artist

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Planting Present Tense, 2015, courtesy of the artist

In the performance piece Planting Present Tense the artist deals with more personal material, a remote memory rooted in the history of her own family. Central elements in this piece are two hanging t-shirts, embroidered with a text, inspired by the last letter Bikoro’s great grandfather –imprisoned in a German labour camp, in North Gabon, during First World War– sent to her daughter, the artist’s grandmother. In the letter, written in a highly metaphorical language, the artist’s ancestor asked his daughter to prepare for him a burial without body, because he would not have been able to come back to her. The preparation of the mourning ritual and of the burial was an extreme plea, the expression of a last hope to find peace, at least in the afterlife. Bikoro appropriates the hidden pain of her grandmother, recollecting and transfiguring the process of mourning within her performative intervention. In the final part of the piece, the artist wears one of the embroidered shirts –a gesture that allows her to physically reconnect with the lost words of her great grandfather– and asks a member of the audience to wear the other, so to join her in the last moment of this commemorative intervention. Then, the artist and the spectator calmly pull out of the fabric the thread composing the painful words, until nothing has left. The last gesture consists in the artist facing another woman, while both are filling up their mouths with the previously unravelled thread.

In this performance Bikoro interprets the burial as a gesture of annihilation, to which follows a creative re-appropriation. The distance between the body and the text –which is an indirect memory, in documentary form– is reduced to the point that the body of the artist literally absorbs the written words, transforming an inherited message into enduring body memories. The act of unravelling the text from the fabric is shared with another person, because even the most intimate and personal memory, when re-presented in the world, becomes part of a common/shared experience of existence, in Merleau-Ponty words: “I do not need to look for the others elsewhere, I find them within my experience, they dwell in the niches which contain what is hidden from me but visible to them”.[4] Lastly, the title of the piece reveals the purpose of the entire action: to plant present tense. The artist finds in the process of remembering forgotten pasts, the seeds of a speculative present, a present that is not yet, that has never been, a present that only a redeemed concept of history and remembrance can inspire:

A chronicler who recites events without distinguishing between major and minor ones acts in accordance with the following truth: nothing that has ever happened should be regarded as lost for history. To be sure, only a redeemed mankind receives the fullness of its past-which is to say, only for a redeemed mankind has its past become citable in all its moments. Each moment it has lived becomes a citation a l’ordre du jour[5]

Renegotiating mythologies

A redeemed history stems from an understanding of time that doesn’t distinguish between past(s), present(s) and future(s). Linear History [with capital ‘h’], the History that figures itself as an incessant continuity of identicalities, is the unilateral History of the winner, of the powerful. This is a history of exclusion, a limited history, therefore an untrue history. To abandon the linear conception of time, in favour of a more dynamic one, an anachronistic one, means to give back to the time of the here-and-now [Jetztzeit][6], to the time of the action, all its potentiality. In other words, to embrace a non-chronological comprehension of time and history can restore individual’s ability to operate as agent of change – means for revolution. Re-appropriation of the past(s) opens up the possibility to intervene on and in the future(s). For Bikoro this process must, first of all, entail a renegotiation of mythologies.

Referring to people of Africa and its Diasporas, the artist states: “We became myths, we became poetry, we became one history in the eyes of the terrorist, in the eyes of the criminal, in the eyes of the winner. We have become the Western fantasy that for so long millions have tried to resist and to correct”[7]. A mythology is a system of images, stories, believes, and superstitions shared by a group of people. The making of a myth is not a natural movement, it is a cultural construction, and as such it can be adjusted to suit the will and intentions of dominant powers. The artist is here talking about all the oppressed peoples, whose histories and traditions have been negated and replaced with artificial, univocal symbols –which are instruments for identification and control. In her works, Bikoro re-appropriates these false mythologies and their symbols – the Star of David, the Dutch wax fabric etc.– and use them as a means to interweave lost, hidden and submerged narratives into the fabric of present and future times. Two performances are clear examples of this artistic mission: El Carrusel | Au Hazard Balthazar and After Sundance.

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, El Carrusel, 2013, Photo by Gabriela Salgado

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, El Carrusel, 2013, Photo by Gabriela Salgado

In El Carrusel the artist reactivates an old carousel, with the help of a donkey –named Balthazar, after the donkey from Robert Bresson’s film Au Hasard Balthazar (1966). Bikoro chooses this animal because it is the bearer of a variety of significances, being varyingly connected to religions and mysticisms. Many cultures see the donkey as a representation of the working class, the proletariat, since it is an animal often used for heavy labour, and widely associated with enslavement and stupidity. The artist defines the donkey a humble and holy creature, she releases its figure from negative superstitions and false symbolisms, to make it an expression of the peoples whose voices have been obscured by the univocal History of the winners. In this work the donkey becomes the symbol of unexpressed and suffocated dreams and imaginations. The artistic gestures is able to activate an imaginative action, which not only starts up the movement of the carousel, but also evokes the very possibility to activate a change in reality by escaping the submission to an imposed system of power: l’imagination au pouvoir![8]

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, After Sundance, 2015, photo by Ash Tanasiychuk

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, After Sundance, 2015, photo by Ash Tanasiychuk

After Sundance is a piece first presented in Vancouver, in the frame of the performance festival Live! Biennale. As usual in the work of Bikoro, the performance has been ideated considering the specific socio-political and historical context of the city in which it was to be presented. The artist goes back to the times of the foundation of Canada and United States, and recovers the lost ceremony of the Sun Dance, traditionally performed by First Nations peoples. The Sun Dance is among the many rituals that have been banned by the new European governments. The neutering of cultural roots was an act of extreme violence, which forced the indigenous people to start a difficult fight against cultural amnesia, a fight that goes on to present day. Bikoro renovates the ritual, in a performance that wants to be a contribution to this struggle for survival. The artist slowly walks on broken glasses, evoking an image of pain that connects with the ceremony –a ceremony of sacrifice– and with the painful loss of beloved traditions suffered by native communities. Bikoro’s performance states, once again, that what is negated and forgotten is still never lost to history. The past remains as a subterranean force in the present and it can manifest itself in fragments, through gestures that carry “a decisive historical and dynamic element”[9], which is what Aby Warburg calls a nachleben, an after-life.

Length of a Legacy

The last work I will consider, in this context, is the installation Length of a Legacy. This piece consists in three clay busts, portraying three Afro-German women, founders of civil right movements during the Second World War, who died in German extermination camps. The sculptures are contained in fishbowls, and covered in water. During the exhibition the water gradually erodes the clay, turning the busts into dust. This installation shows, visually and physically, the effect of a destructive action on the surface of memory, the capacity of the power of negation to corrode and crush historical and cultural awareness.

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Length of a Legacy, 2015, courtesy of the artist

Nathalie Mba Bikoro, Length of a Legacy, 2015, courtesy of the artist

To sustain the after-life of obscured, eroded, erased historical events means to defend and support an endangered legacy, by constantly re-affirming its existence in the world. Bikoro’s main purpose, as an artist and researcher, is to build up a living archive. An archive of the future, whose aim is not to fulfil the void left by the defeated, the dead, the drowned, but rather to show its unfathomable presence as a resisting creative element: “The attraction of the archive will always be as much about what they lack as what they contain. Those gaps and holes, all the things left unfinished, are often the possibilities”[10].

To conclude, I would like to return to the question asked by those enslaved men and women, sealing from the coasts of West Africa to the unknown, who speak through the pen of Édouard Glissant: is there somewhere a nonworld that no ancestor will haunt? As long as a weak memory survives, embodied in gestures and evoked in images, no land will be a nonworld; this is the length of our human legacy.