Their aim was to raise the profile of black artists and the Afro-Caribbean community through a series of sculptures, paintings and exhibitions. It was also an eye-opener for contemporary white artists as this political movement encouraged conversations on art reflecting culture and the state of how mainstream art did not include the experiences of the black population.

Chistabel Samuel on the British BLK Art Group

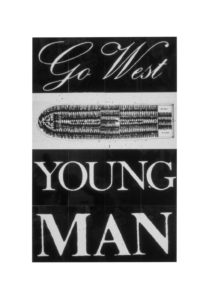

Go West Young Man, poster Keith Piper, 1987.

A Look at the BLK Art Group

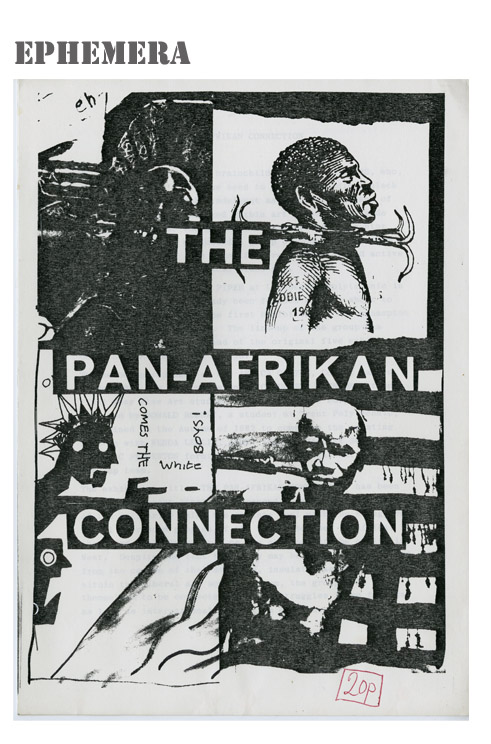

The year was 1979 when Britain saw the initial birth of the BLK Art Group. Formed in Wolverhampton and originally coined the Pan-Afrikan Connection, the BLK Art Group was the UK’s counterpart to radical black projects occurring in the United States. Inspired by America’s Black Arts Movement (BAM), which was part of the larger Black Power Movement, the BLK Art Group similarly wanted to empower and encourage a black voice and resources within Britain. Running for about five years the group’s emergence came at a critical time globally and within British politics.

Poster Pan Afrikan Connection.

In the 1970s through to the 1980s, the British economy was on the decline. Meanwhile more and more educated young black people were graduating from school. Unemployment was high, institutions like the police and army were still innately racist and there was still an extreme level of neo-Fascist activity running through society.

Wolverhampton, based in the West Midlands, was a heavily industrial area populated by employees and factory workers from the Caribbean. This influx of immigrants brought into the country to work led to a large Afro-Caribbean community settling in Britain as their new home. The diaspora raised its second-generation who grew into the men and women that would later fuel the BLK Art Group.

As the UK’s manufacturing industries were ailing, unemployment, anger and rebellion was on the rise. Retrospectively nowhere was better or provided more fertile breeding ground for a revolution than the Midlands with its dense population of immigrants and disenfranchised groups.

Its members were young artists seeking to form a bold identity and challenge the ideas of culture, blackness and race-relations within the United Kingdom at a time when many rights were still out of reach and racism was common. Art was the medium with which to vocalize and express the concerns, philosophy and anger felt by many.

Their aim was to raise the profile of black artists and the Afro-Caribbean community through a series of sculptures, paintings and exhibitions. It was also an eye-opener for contemporary white artists as this political movement encouraged conversations on art reflecting culture and the state of how mainstream art did not include the experiences of the black population.

Their lateral and free-thinking ideology traced modern Britain to its colonial roots as well as catching inspiration from the American Civil Rights Movement, South Africa’s struggle with apartheid and the different difficult positions of social unrest rippling through the country.

In 1983 the group organized the First National Black Art Convention at the Polytechnic in Wolverhampton where many of its members studied. This included Claudette Johnson who joined the group about a year earlier. Johnson brought a feminist approach to the collective through her large-scale drawings of black women. Her powerful imagery is rooted in an African heritage; sensual, colorful and demanding viewer’s attention.

In addition to the array of art shows, the legacy of the movement included creating shared social spaces for which the growing number of collaborators could use. This proved a difficult struggle that the group overcame eventually through grit and determination and thus became one of their most underrated achievements.

There were several members but notable contributors of the group included Donald Rodney, Marlene Smith, and Eddie Chambers who we will look at more detail below.

Donald Rodney

As one of the most known figures of the BLK Art Group, Donald Rodney used a highly personalized approach in his work. Born into a large Jamaican family – Rodney was the last of twelve children – he honed his skill in his late teens after several trips to the hospital. Suffering from sickle-cell anaemia, Rodney often fell ill and had a lot of time waiting and filled many sketchbooks with his work.

This led to enrolling in the early 1980s into Trent Polytechnic where he met Keith Piper, another important member of the BLK Art Group. There Rodney was inspired to produce what would become his personal style. His disease became more and more enshrined as a metaphor for black suffering and emasculation. For example in House of my Father Rodney produced a delicate palm-sized house, made from his own skin and held together by one pin. The structure is balanced on his hand and painfully demonstrates the beauty and delicate nature of humanity and in this case contemporary black experience.

Donald Rodney, House of My Father, 1986-1987

In his exhibition Trophies of the Empire he explores the history of colonialism, the empire and the legacy of the slave trade. Within the collection one piece entitled Trophies stands out. On the surface it is a typical cabinet display of trophies, gold and silver, in a line. However on closer inspection the engravings beneath them reveal lines like “Black people are second class citizens”, “Black men are always on the defensive” or Black people have small IQs”.

Donald Rodney, Double Think, 1992 (trophies with text)

By bringing these generalizations to the fore against the backdrop of the trophies, Rodney conflates the idea of black immigrants as the ‘trophies’ of Imperialism as well as the victims of its pilfering. Just like the trophies often found in cases, the stereotyping and discriminations are as well protected and set-in as the engravings found on them.

Rodney died in his late thirties, a victim to the sickle-cell anaemia which affected his life but not without making his mark as one of the most creative and notable black artists of his generation.

Marlene Smith

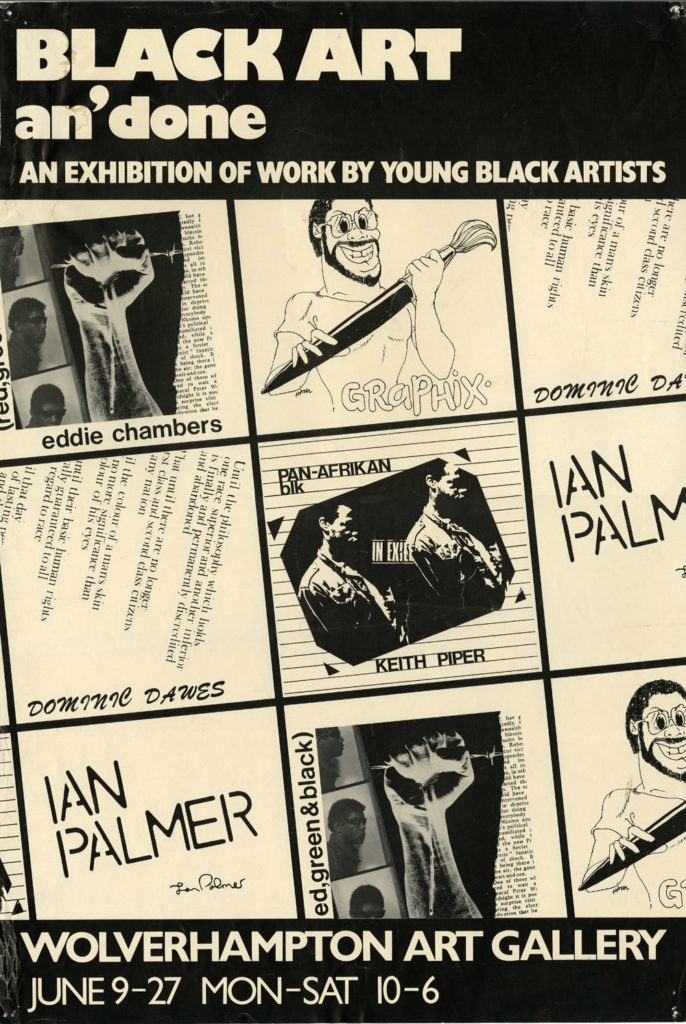

Marlene Smith to this day is still active and involved in the art scene including her role as director of The Public, an art gallery in West Bromwich UK. However thirty or so years earlier, Smith was elbows-deep in organizing key BLK Art exhibitions such as Black Art an’ Done.

Poster exhibition Black Art an’ Done

This was an important exhibition in 1981 featuring Andrew Hazel, Ian Palmer and Keith Piper, whose statement said “To me, the black art student cannot afford the luxury of complacency as enjoyed by many of his white counterparts…The black art student, by his very blackness finds himself drawn towards the epicenter of social tension. He is forced to respond to the urgency of the hour…Let us strive by any means to raise the revolutionary social, political and economic barriers which this man has placed all around us, and within our very minds”.

Curating pieces from these artists formed and shaped a sense of the BLK Art Group as a collective and their objectives as a whole. Without these key events overseen by Smith the BLK Art Group’s prolific rise would have surely been curbed.

Eddie Chambers

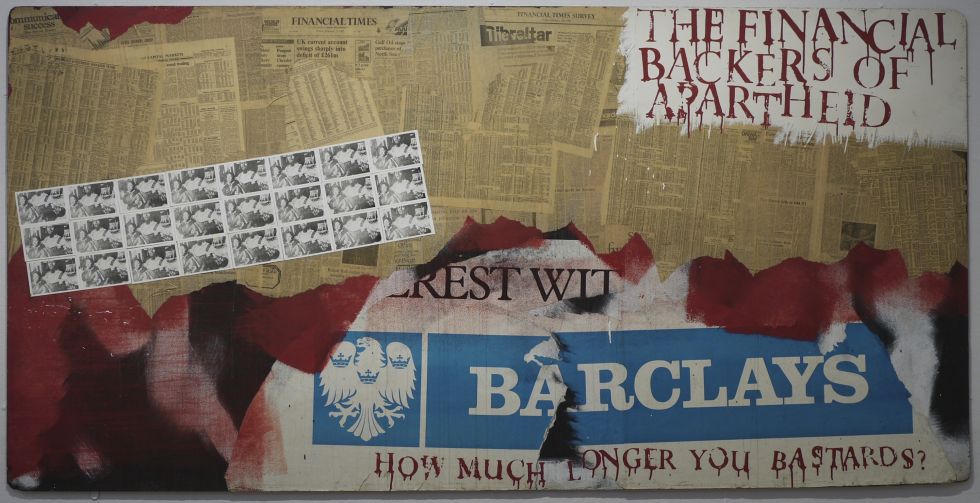

Hailing from Wolverhampton, Eddie has had a long list of artistic and academic achievements. Currently living between England, Scotland and the United States, Chambers received a BA in Fine Art and a PhD in Art History. He was involved in curating the Black Art An’ Done exhibit with Marlene Smith and several black interest events including producing his work in solo exhibitions as a visual artist.

Chambers’ writing has also investigated and promoted black experiences including articles and essays in published magazines such as Art Monthly, Race Today and Creative Camera.

Later Chambers founded an African and Asian research facility dedicated to recording and archiving British black artists. The African and Asian Visual Artists’ Archive (AAVAA) ran for years until its materials were eventually returned to him.

Eddie Chamers, How Much Longer, 1984.

Looking at these three figures in a little more detail reveals the significance that a collection of artists like the BLK Art Group had in influencing, motivating and inspiring contemporary artists and communities. Without this movement could the landscape of art in Britain ever be the same? Would it have been as progressive without the push of its members?

Although formed and defined by their blackness, the group’s wider impact on white and non-black audiences was just as important. Painting a window into the black community and more significantly allowing access into it through art – which is always a universal tool for rousing emotions and thought – drew in crowds of people and its impact is still around today. Nowadays the subject of research papers and academic work, the BLK Art Group has evolved from a revolutionary concept into a historically resonant pinprick in the timeline of British civil rights.

In 2011 Marlene Smith, Keith Piper and Claudette Johnson set up the BLK Art Group Research Project which, “took a renewed examination of the archives and historical legacies of the BLK Art Group”. Seeking to promote debate and academic understanding of the movement, this new project is a brilliant way of retrospectively understanding the wider impact as well as contextualizing the group through a post-modern approach. In 2012 the project held a symposium and an exhibition at the University of Wolverhampton.

Although current activity seems dormant, its individual members are still globally active and the academic interest in the group’s work remains strong. It seems likely that with the social and political climate in the UK and America being so unstable, interest in the BLK Art Group may be renewed. In recent years the Black Lives Matter campaign has been launched and the artwork produced as a result of its inception can be paralleled with the ideology and aims of its predecessor.

Fundamentally, as long as there are protests to mistreatment, inequalities and discrimination, rebellion will find its voice through art. As the BLK Art Group has demonstrated, fighting the powers-that-be with a brush and canvas can be one of the most effective means of making a difference to the lives of black people.