The miracle is, in fact, that, given the overwhelming odds against women, or blacks, so many of both have managed to achieve so much sheer excellence, in the face of violent, selective and shifting definitions of history and art, and in the face of direct suppression, omission, gatekeeping, lack of transparency, and outright unprincipled opportunism of unscrupulous gallerists, and their ilk.

Nkule Mabaso on the position of black female artists.

Nkule Mabaso, portrait.

[1]On Black women’s Creativity and the Future Imperfect: Thoughts, Propositions, Issues

Black female practitioners in the arts are fundamentally embedded in a context that has challenged their very right to exist, and the resulting absence of black women in art has been a self-evidential critique of this tendency in the discipline.

Maria Lugones in “Toward a Decolonial Feminism” begins her essay thus:

Modernity organizes the world ontologically in terms of atomic, homogeneous, separable categories. Contemporary women of color and third-world women’s critique of feminist universalism centers the claim that the intersection of race, class, sexuality, and gender exceeds the categories of modernity. If woman and black are terms for homogeneous, atomic, separable categories, then their intersection shows us the absence of black women rather than their presence.[2]

In the face of these and other series of absences that black women face, feminist, womanist, and decolonial efforts are performed to fill these apparent voids through attempts that:

… dig up examples of worthy or insufficiently appreciated women artists throughout history; to rehabilitate rather modest, if interesting and productive careers; to “rediscover” forgotten female painters and make out a case for them.[3]

A commendable and recent example is Nontobeko Ntombela’s 2012 restaging of Gladys Mgudlandlu’s first commercial exhibition at the Contact magazine boardroom in Cape Town in 1961. Ntombela drew on curatorial and exhibition practices to navigate the archive of Mgudlandlu’s public acclaim and positioning within histories of South African art. Besides the use of art historical provenance to recuperate details of the works on the original exhibition, Ntombela’s effort involved locating unrecognized and unheralded works, scattered and long out of circulation, of two[4] black women painters who were so ‘extraordinary’ they managed to have their ideas and production preserved, yet whose absence in histories of art bears the contradictions of a canon that relegates their production to the margin.

The contradiction of addressing the ‘question’ of black women and their attendant ‘absences’ falsifies the nature of the issue and tacitly reinforces negative stereotypes presenting themselves as simple reflections of reality when in fact they are ideologically or culturally constructed. For example, the absence of recognition of and for the work of black women artists is actually a problem of their having to work in a stultifying, oppressive, and deeply disturbing environment in which the life-experiences and traditions of black producers, in general, have no relevance in implicitly racist environments.

To attempt to reclaim the ideas and production of an internationalized black womanhood who have been silenced is to perform a flawed exercise. On the surface, this is certainly worth the effort, both in adding to general knowledge of black women’s achievement, and of art history largely, but it does nothing to question the assumptions lying behind the present obscurity and continued institutional and historical omission of black women in art.

Lubaina Himid

(right) work of Himid presented in 5 Black Women, 1983

Diasporian curator Lubaina Himid, operating in the 1980s in Britain, curated such essential exhibitions as 5 Black Women (1983) at the Africa Centre and Black Woman Time Now (1983) at the Battersea Art Centre, and Looking back (1989) at the Hayward Gallery. Himid’s practice inspired another generation of writers and artists, among them Maud Sulter, the curator of The Other Story, and The Thin Black Line, and author and editor of Passion: Black women’s Creativity. Sulter approached her work as an opportunity to “position women of color into the Western Art Canon, where we have been conspicuously absent.”[5] Her efforts took place in the early 1980s, culminating in a list of exhibitions of creative work by black women artists in Britain operating at that time. In an interview, Sulter recounts how in 1982 she felt that it was too easy for what were “essentially white women’s publishers culling some short stories and poems from Black women and then hailing the fact that they had published x-dozen black women writers”, especially at a time when they were earning significant incomes from black women writers.

Poster for the exhibition The Thin Black Line

The absence of these exhibitions and writings in the curriculum and in discussions on visual history invalidates the efforts of black women on the continent and diaspora. It is the result of a manufactured failure that propagates the supposed absences, therefore the adage holds true: black women must read history for clues not facts[6].

Gabi Ngcobo, most explicitly in her staging of the Center for Historical Reenactments (CHR) inaugural exhibition PASS-AGES: references & footnotes, literally interferes with the accepted understanding of ‘history’ to scan poignant moments from images and personages and mine them for gold. The exhibition takes metonymically the task of addressing historical and current omissions, suggesting different historical readings for visual histories that disproportionally privilege and acknowledge certain narratives, and their attendant questions of how history affects how we receive or understand art and visual histories. One’s actions as a curator have the possibility to reread history and its contextual implications and play a major role in the situating of less-presented subjectivities.

Mary Sibande (copyright artist/courtesy MOMO Gallery)

For those who have never seen the actual exhibition, the catalogue offers two pathways of exploration; of interest to me in the service of this text are the contributions by Hlonipha Mokoena and Desiree Lewis, and how they situate the specificities of black womanhood in South Africa. These texts refer to the works of Mary Sibande and Zanele Muholi, specifically questioning the power relations of black and white women in domestic situation/ interiors. Through the figure of the maid, the black female body broadly becomes the surface where the past is in confluence with the present, and on to which the questions regarding domestic work as a site of domination are projected.

The fact that you who are reading this now may be encountering the names of these women and their production here for the first time not only reveals the false nature of the lacuna, but also explicitly demonstrates that the pageantry of the short-term hypervisibility that black cultural producers find themselves subject to is an extreme form of ridicule. It is a visibility with no trajectory that serves essentially to entrench exclusions; exemplify inclusion in the short term, after which these efforts are simply written out of history in the long term, reproducing an absence, always in need of addressing, ad infinitum.

Manhood.

Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi is an artist whose work and biography have been used to perpetuate ideas about an intrinsic, intuitive ethnic[7] characteristic that validates applying different standard to the work of black artists., Mme Sebidi’s work is problematically often inscribed into a narrow frame that associates her, and her production, with the ‘rural’: a framework that harbingers black women as the guardians of a ‘traditional knowledge’ that participates in an indigenous knowledge continuum informed by living experience and ancestral voices imparted through narration. Associating black women with being rural is not a particularly original gesture; it forms part of the framework that drives the continued marginalization of black women from the benefits of modernity, and insidiously denies them greatness and analytical aptitude.

These closed narratives the criticality of the observations carried in the work, and doubly her urgency and contemporaneous analysis of the disruption, through colonialism/neo-colonialism, of what could be understood as traditional ways of teaching.

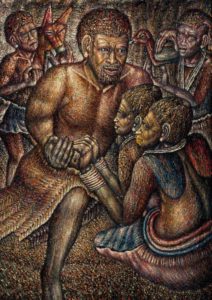

The First Wife Has Chosen.

Mme Sebidi’s production of paintings defies simple categorizations that present woman as the site of cultural interiority and ethnic artistic sensibility, and the bearer of authentic heritage, by problematizing traditional culture—and its hierarchical social order—as an area also heavily manipulated by the colonial state in the interests of capitalism. Her paintings, and their allusions to an indigeneity freighted with assumptions from specific moral traditions that enjoys proximity with modernism, provide excellent analyses of the destruction of the social fabric of rural communities from varying vantage points. For example, the works touch on how capitalist systems and wage employment have destroyed the traditional social infrastructure and dragged all communities into the dominant capitalist system, displacing families through migrant labor, without ever taking a representative approach.

Looking at Mme Sebidi’s paintings from a psychoanalytic framework, the present is offered as made up of memories and perceptions from the past. A dominant view is that the past is ambiguous, as historical material is always over-determined and multi-layered. Within this viewpoint, the past always adds to the present, and the opposite process is simultaneously in operation, as, in going over the past, new events and/or mental states are recollected so that the past becomes a kind of layering of narratives, each ordering the revival of the past in different ways with different intentions[8].

Mme Sebidi is an interesting figure in that she has defied conventional notions associated with the black womanhood of her era[9]. She embodies instead a radical black female subjectivity, unencumbered by the effects of enforced domesticity. She inhabits the world as an artist, remaining childless and unmarried in a societal context where in the “enactment of masculine entitlement and privilege women are subject to spectacles” that “starkly create the most crude and debased imagining of patriarchal control over women”[10].

The function Sebidi’s work employs is to mirror the ways that originary and traditionalist histories have been constructed, then recounted, analyzed, dissected, measured, torn apart and distorted into the bastardised manifestations of domesticity and patriarchy that we encounter. Vitally, she eloquently captures how “women continue to struggle for their emancipation”, whether through their work or writings, to challenge “the seven mountains of colonialism, neo-colonialism, and patriarchy, and … despite the efforts of colonizers”[11] to disrupt ‘localized’ social practices.

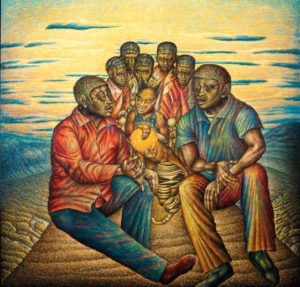

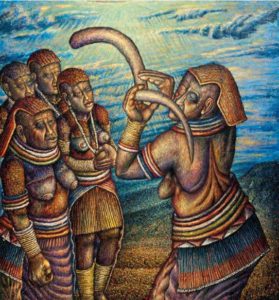

The People Are Called

Black women’s creativity cannot help but be revolutionary in its potential. It confronts racism, sexism, privilege, and abuse, but tries soulfully not to lose its integrity. It holds out for aesthetic integrity over mere rhetoric, active passion over passive submission. Sebidi production fits firmly in this tradition, where visual culture becomes “the place where battles are fought and the strategies of resistance negotiated”[12].

Black women have been, in many ways, oppressed by theories have looked unsympathetically and unethically at them, and by the implications set in questioning modes conditioned and falsified by the manner in which they are posed. Linda Smith in Decolonizing Methodologies, for people who are engaged in or beginning to fight back against the constructed invisibility, whether in academic or artistic communities, and who are carrying out research.

The miracle is, in fact, that, given the overwhelming odds against women, or blacks, so many of both have managed to achieve so much sheer excellence, in the face of violent, selective and shifting definitions of history and art, and in the face of direct suppression, omission, gatekeeping, lack of transparency, and outright unprincipled opportunism of unscrupulous gallerists, and their ilk.

References

Writing Diaspora: Tactics of Intervention in Contemporary Cultural Studies. Indiana University Press

0 Avail: 0 p 4. In “PASS-AGES: references & footnotes”. Printed by Center for Historical Reenactments. The Use of Visual Arts in Contemporary African Novels Avail: 0

Nochlin, L. 1988. Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? Avail: 147-158

Ogundipe-Leslie, M. 1994. African women, culture and another development. In Recreating ourselves: African women and critical transformations. Trenton: Africa World Press.

Rosen. 1993. “Art History and Myth-Making in South Africa: The Example of Azaria Mbatha” pp 9-22. 1993. Avail: