The artists are reclaiming the street, personalizing public space, critically reflecting on how it has been, and is continuously, appropriated by others and the agendas they push. In entering this realm, with their own work in the form of posters, these artists alter the urban fabric of the city through its material form and resulting dialogue. They create physical sites of resistance to the dominant hegemony and communicate to people who take up and occupy these everyday spaces – roadsides, bus stops, estates, street corners etc.

Craig Halliday on ‘Political Jamming’ by the group #NOIMPOSTERSHERE from Nairobi.

#NOIMPOSTERSHERE: Political Jamming

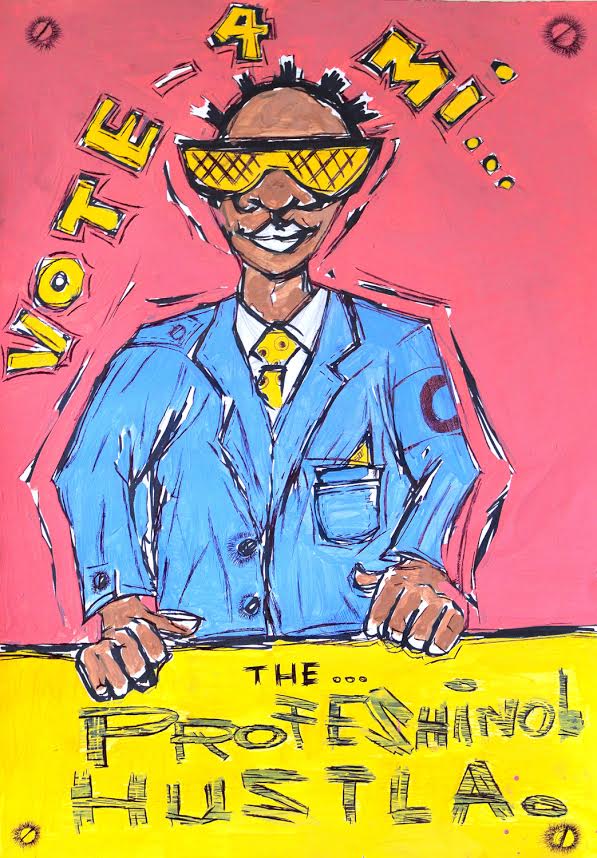

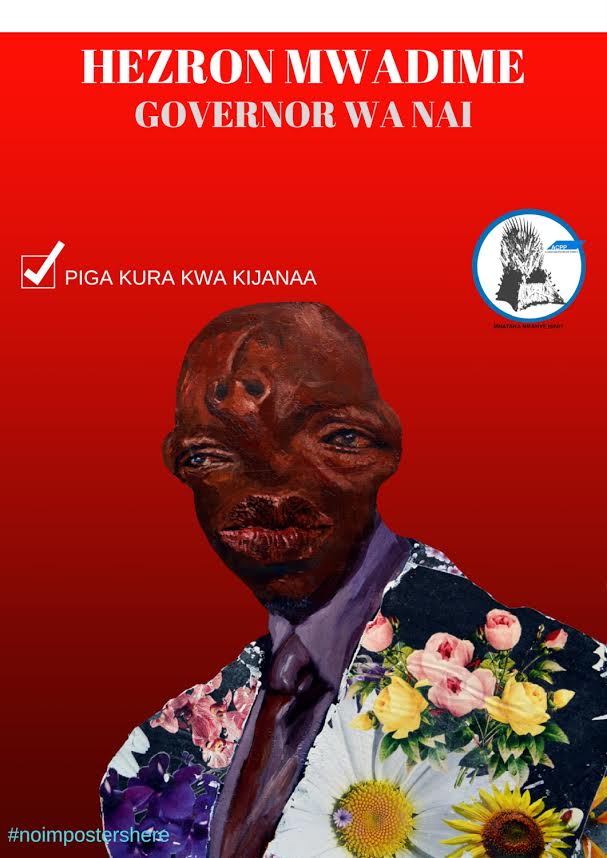

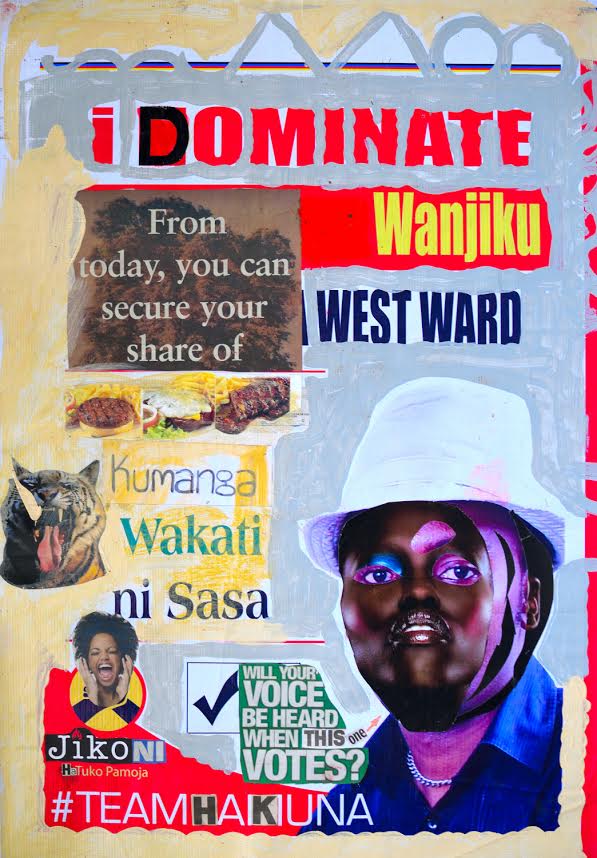

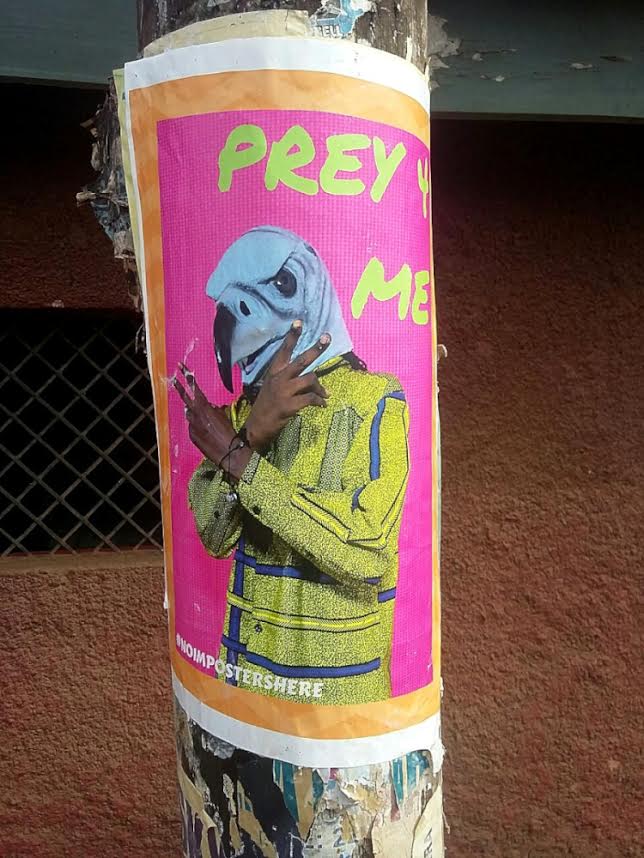

Today’s political and social landscape is one filled with imagery, made up of signs, symbols and spectacle. The role of visibility has become imperative in mobilizing the public or drawing attention to a cause or topic. The images which fulfil our landscapes attract audiences and entice viewers into narratives that are grasped at a glance. Reacting to this visual environment has been a surge in the utilization of artistic practices and creative strategies in order to bring about societal transformation. In Nairobi, a group of anonymous artists, going by the name of #NOIMPOSTERSHERE, are interrupting the cityscape with faux campaign posters during the run up to Kenya’s 2017 general elections; this can be seen as challenging the status quo and expanding public discourse in a multiplicity of social spaces.

Subverting the Visual Landscape of Campaign Posters

In the quest for visual dominance political parties and candidates spend large amounts of money campaigning in the run up to elections. Campaign posters, due to their affordability and visibility in the public sphere, are a popular tool to attract the electorate. In Nairobi, during the run up to elections, thousands of posters are strategically positioned (covering walls, fences, kiosks, bus shelters and buildings), where they are seen by hundreds of people every day. It has been said that “If political posters were ugali, Kenya would be the best fed African country”.[i] The aim of campaign posters is to familiarize the populace to the candidate; to present him/her in a positive light; to win over someone’s vote. They are a method of mass marketing, conforming to a particular style (candidate’s portrait, symbolically meaningful color, name of candidate and party, position running for, and slogan – are all general characteristics of such posters). Seldom do they express party policies or facts – that in itself says something about the state of Kenyan politics today.

The pasting of posters in everyday urban spaces creates a new aesthetic in people’s neighborhoods – albeit one every 5 years. The mass of posters (and destruction or defacing of some) signify the extent to which parties and candidates will go to win.[ii] The visual imprint of these posters is perhaps the most visually symbolic aspect of election campaigns. However, this raises a number of questions. What do such posters say of Kenyan politics? Are posters simply there to canvas votes? Does one really know who is portrayed in these posters and what their interests are? How do posters assist voters in reaching informed decisions? Is the public stimulated into political debate and encouraged to participate in the democratic process from seeing these posters?

These questions are asked by an anonymous group of artists, active in Nairobi, who produce work by the name #NOIMPOSTERSHERE. According to the website, the group has “a mission of interrupting the cityscape that becomes polluted with political campaign posters we are forced to engage with during the run up to Kenya’s 2017 general elections.”[iii] Their name is a play on the command ‘No Posters Here’, which covers many of the walls across the city. The group call this a ‘slogan of authority’, which can be connected to the control and appropriation of city spaces, what is and isn’t seen and who has the power to decide. Their reference to ‘imposters’ (impostors) probably signifies the individuals portrayed in the campaign posters – depicting (aspiring) politicians as individuals pretending to be someone they are not for their own personal gain. Though the group can also be seen as imposters, as they subvert the visual landscape of election campaigns by creating and pasting their own posters alongside ‘originals’ in the hope of prompting dialogue and reflection around elections and politics.[iv]

Culture Jamming or Political Jamming?

The method employed by #NOIMPOSTERSHERE have close ties to ‘Culture Jamming’; a creative movement aimed at disrupting the dominance of corporate media, advertising and the marketization of public life. In the book ‘Activism! Direct Action, Hacktivism and the Future of Society’, Tim Jordan describes it as “an attempt to reverse and transgress the meaning of cultural codes whose primary aim is to persuade us to buy something or be someone”[v]. Anna Wacławek, in the book ‘Graffiti and Street Art’, says the practice of Culture Jamming is a “direct way to answer back to those who have financial, and by extension visual, control over cityscapes”.[vi] Wacławek goes on to say that through subverting key components of original advertisements “artists effectively empower the public in their experience of their environment and challenge the status quo.”[vii] However, Culture Jamming can also be seen as a way of reclaiming public space where advertising messages have become the only ones permitted. In the book ‘No Logo’, Naomi Klein speaks of this saying “Culture jamming badly rejects the idea that marketing – because it buys its way into our public space – must be passively accepted as a one-way information flow.”[viii] These concepts of Culture Jamming are overtly targeted towards the corporate world and capitalist agendas. However, if one replaces the product with the (aspiring) politician, and the corporations with political parties, then the project #NOIMPOSTERSHERE can be seen as doing what Culture Jamming strives for – though through a political lens, one that might be termed “Political Jamming”.[ix]

Confronting the Control of Public Space

It has been argued that to reach or persuade audiences in politics some amount of public spectacle is necessary.[x] Through the creation of what could be described as multiple ‘public art exhibitions’ dotted around the city and formed through the pasting of hundreds of posters, #NOIMPOSTERSHERE creates new spaces within the city, spaces that are formed out of spectacles and ones which provide sites where different forms of discourse and public engagement can take place. The project challenges the production of city space that is largely controlled by powers that do not place the public interest at heart. In Nairobi, like many cities across the world, advertising billboards and signs have become common features – appearing as giant monuments to capitalism. They offer the everyday passer-by a look into the ‘ideal life’. Streets become a space visually dominated by corporate influence. However, during election periods these spaces become diluted by the influx of campaign posters and advertising. The use of public space in this way represents egotistical strategies in appropriating city space for corporate or political profit. By disseminating their work in the same space, #NOIMPOSTERSHERE challenges what has become passively accepted and resists the commercialization of public space. The artists are reclaiming the street, personalizing public space, critically reflecting on how it has been, and is continuously, appropriated by others and the agendas they push. In entering this realm, with their own work in the form of posters, these artists alter the urban fabric of the city through its material form and resulting dialogue. They create physical sites of resistance to the dominant hegemony and communicate to people who take up and occupy these everyday spaces – roadsides, bus stops, estates, street corners etc. Such actions may not at first appear significant. However, a vibrant society depends upon the availability of physical public space. While in reality campaign posters and adverts are often pasted on ‘private’ property, they do nevertheless fill spaces in which the public have the freedom to occupy and thus everyday passers-by become participants in that urban environment. If, in these spaces, certain viewpoints are excluded, one voice overpowers others, or only certain truths are represented, then the public interest becomes eroded. As a result, the urban spaces we walk, encounter and participate in the city may appear public on the surface, though in actuality they are controlled more and more by corporate, and at times political, powers who seek to push their agendas into every corner of social life. I argue that #NOIMPOSTERSHERE contributes (in its own small but significant way) in countering this threat by providing alternative voices and opinions, while at the same time re-appropriating public space for public life. This is achieved through the pasting of faux campaign posters – though what are the narratives these posters present and can one really say they have societies interest in mind?

Faux Posters

On the group’s website it shows over 25 poster designs. These posters (which have been pasted across Nairobi) act as a critique to Kenyan politics and democracy. #NOIMPOSTERSHERE achieves this through their own subtle way – incorporating humor, satire and directness in their poster designs. For example, a series of posters show hyenas, pigs and vultures who are dressed in colored suits set against a brightly decorated backdrop. The use of these animals relates to local narratives in which the hyena, pig and vulture are consistently typecast as greedy, opportunistic, scavenging, taking advantage of the weak, and looking for instant gratification. Accompanying text references recent happenings in the country that have been politicized – such as the Unga Crisis; politicians saying a lot – but not really saying anything (blah, blah, blah); the electorate entering a ‘ZOMBIE MODE’ state – perhaps in reference to the continuation of voting along identity based lines; or how the political establishment have been taking Kenyans for a ride since independence. Other posters rely solely on text. For example, one poster displays annual dates from 1990 -2019 but leaves the years when Kenya held General Elections (1992, 1997, 2002, 2007, 2013 and 2017) blank. This poster comments on the role of elections in democracy, highlighting how despite the significance placed on elections in Kenya (and elsewhere), elections alone do not equate to democracy; and it should be remembered that life for the everyday citizen continues once this event has passed. Another purely text-based poster reads ‘We the People Want’, listing pertinent issues close to the hearts of many Kenyans. In another set of posters ‘original’ campaign posters have been appropriated and recreated though collage techniques. This approach distorts what is genuine with what is fabricated. This method has also been applied to another series of posters in which candidates’ faces are painted in a deformed, twisted, misleading and fuzzy manner – perhaps as a reference to their own characteristics, though also the campaign process itself and the ‘game’ of politics more broadly.

A number of the posters created by the group #NOIMPOSTERSHERE use a similar format to ‘authentic’ or ‘original’ posters. The #NOIMPOSTERSHERE posters are not attempting to come across as real, though what they do present is enough likeness to the ‘real thing’ to cause curiosity. This method can be seen as a distortion of reality and comments on what is real and fake. This is pertinent given the mediating role of media in distorting events and truths. Writing in the Daily Nation, in April this year, Gabrielle Lynch (Professor of Comparative Politics at Warwick University) speaks of the problem of ‘fake news’ that has circulated parts of Kenya through leaflets, posters, mock newspaper covers and rumors which are easy to spread quickly through new technology and digital platforms (Facebook, Whatsapp and Twitter etc.)[xi] The posters themselves are not necessarily acting as purveyors of truth – after all not all (aspiring) politicians are self-serving and in it for themselves (though many are) – but through the juxtaposition of real and faux they comment on the infiltration of fake or deceitful narratives entering the public sphere, propagated by not only those from the establishment but also the everyday person.

Summary

While it is common for people to speak about the public sphere becoming more and more digitized, moving into online platforms (such as Twitter and Facebook), #NOIMPOSTERSHERE communicates with real people who take up, occupy and share physical spaces within the city. The group is able to reach mass audiences across Nairobi through the use of posters – which would not be possible through other forms of art. While not all will be advocates of #NOIMPOSTERSHERE (I am sure there are those who criticize their approach and see it as unhelpful, provocative or even divisive in the run up to the elections), the group does nevertheless create spaces for democratic performance; they argue that the need for such space must not be overlooked; society must not become passive in conforming to the control of public space but rather work to reclaim it; the group also challenge unequal patterns of access to these space and who has opportunities to participate in the public sphere. Whoever these artists are (their identity would simply be a distraction from their mission) #NOIMPOSTERSHERE’s creative practices and actions are powerful tool in causing the public to question the status quo and disrupt everyday views on life and control over public space.

[i] ‘If political posters were ugali, Kenya would be the best fed African country’, Daily Nation, Wednesday January 9 2013. http://www.nation.co.ke/oped/Opinion/440808-1661668-34k5ws/index.html

[ii] For example during the party primaries it was reported that two young men pasting political poster over a rival’s poster were attacked by supporters of the poster’s candidate they were covering. One man died and another was seriously injured. The incident took place in Pangani, Nairobi. See http://www.nation.co.ke/news/politics/Millie-Odhiambo-house-torched-in-Mbita/1064-3904834-amlspk/index.html

[iii] See the #NOIMPOSTERSHERE website www.noimpostershere.co.ke

[iv] ibid

[v] See the book ‘Activism! Direct Action, Hacktivism and the Future of Society’ by Tim Jordan 2002 pg. 102. London: Reaktion Books Ltd.

[vi] See the book ‘Graffiti and Street Art’ by Anna Wacławek 2011. Thames & Hudson world of art. Pg. 189

[vii] ibid

[viii] See the book ‘No Logo’ by Naomi Klein 2000, Flamingo Publishing. Quote from 10th Anniversary Edition, published by Fourth Estate 2010 pg.281

[ix] See the article ‘Jamming the political: beyond counter-hegemonic practices’ by Bart Cammaerts 2007. Continuum: journal of media & cultural studies, 21 (1). pg. 71-90.

[x] See the book ‘Democracy and Public Space – The Physical Sites of Democratic Performance’, by John Parkinson 2012 – Oxford University Press

[xi] See ‘Be warned, it is the season of fake news’, Daily Nation, Saturday April 15 2017. http://www.nation.co.ke/oped/Opinion/-season-of-fake-news/440808-3890034-3iko8n/index.html