As was often the case with its predecessors, the role of social developments is very much apparent in the works of the participating artists of Dak’Art 2018. There is no lack of sensible content. Fortunately that does not lead to pamphletistic art. It is precisely the power of a lot of contemporary African art that content and form are integrated.

The Dak’Art remains a biennial that counts.

Rob Perrée on the 13th edition of Dak’Art in Dakar, Senegal

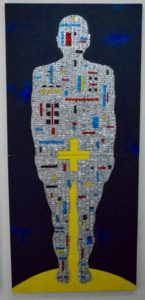

Wallsculpture of Olanrewaju Tejuoso (detail)

DAK’ART 2018

A biennial that counts

I passed on the last two Dak’Artsprograms. Great was the surprise when I recently visited the thirteenth edition. A brand new airport – built by Turks – far enough away from the city to give space to a new capital. The first, mostly tall buildings are already there. The road to it is ready. China is the most important developer, it is said. The old airport is maintained. “Only for the president”, says my critical taxi driver.

In Dakar, one high apartment building is required after another. Concrete skeletons that grey the streets. As if I were walking around in South Korea or China. The Chinese are also responsible for a new Grand Théater National and for the adjacent Musée des Civilisations Noires (MCN). Many old buildings in the center (Plateau) are being demolished and replaced by architectural failures that leave little room for many people. From the middle class, to be precise. The ‘ordinary’ people can’t afford such a housing.

*

Does Senegal step into the African train of prosperity? Has a sudden prosperity given the country a move in the right direction? Opinions differ on this. When I ask people who pays for all that, they point to themselves. The taxpayer. Poverty is still high, unemployment has not diminished. The arrival of Chinese and Turks does not change that. After all, they often work exclusively with their own people. Is the change then the result of a president with ambition and vision? That undoubtedly plays a role. However, there is also a president with a big ego, with dictatorial features, who imprison detrimental opponents and bribe the poor to vote for him. An old song that is apparently still sung. A new Senegal must underline his status. And, caress his ego.

Within this gray and dubious context, the Senegalese remain friendly people who live day to day and have a hard time ruining their good mood. They still try to smear you a large variety of goods. The whole day long.

Simon Njami (Photo: Mathias Schormann).

The Dak’Art does not seem to attract much of these developments. For thirteen editions, she has succeeded in bringing African art to the attention of a fairly large audience. The latest editions have changed in the sense that they are largely determined by an independent curator who makes her or his choice from the range. Every artist can still come up with a proposal, but there is less and less chance of making the final selection. The ever expanding Off program offers a solution for those artists. The Ministry of Culture has been the main sponsor for all those years, although it seems to be increasingly remote.

Just like 2 years ago Simon Njami (1962) is the head curator of the edition of this year. A black Swiss writer and curator who has many large exhibitions to his name.

This time he chose the theme The Red Hour, a reference to Aimé Césare, one of the fathers of the Negritude, extracted from his play ‘And the dogs were silent’. It would stand for “emancipation, freedom and responsibility”. A beautiful explanation that I see at the most dimly processed in the work shown. Red is mainly degraded to a striking color that is used to attract the attention of the public. At many venues it colors the outside.

The main exhibition shows the work of 75 artists from 33 countries. It is presented in the old Palace of Justice, a beautifully run down building with a huge, partly covered courtyard and dozens of small and somewhat less smal rooms. Everything except a clean swept white cube. The art gets every chance to define the space. Five international curators provide their own presentation in the IFAN museum. A large tent next to the National Theater houses presentations of Rwanda and Tunisia. They look more like tourist offices than galleries of art. In between those 2 national pavilions there is a part that focuses on art from the region. In addition, there are some smaller exhibitions in other museums.

The problem of most biennials is that it is physically impossible to visit all the venues – the IN’s and the OFF’s together. This also applies to Dak’Art 2018. More than 300 OFF locations force you to a small selection. I wonder more and more often whether organizers of this type of events should not be more selective. Beforehand. That would benefit the quality of the whole.

2.

Laeïla Adjovi (Benin)

© Laeïla Adjovi/Loïc Hoquet, Courtesy of the artist

Adjovi is a journalist and artist. Malaïka Dotou Sankofa (2016) is a series of photographs that tell the story of a fictional, androgynous person. With wings made of colorful feathers. The first name means angel in Wolof, the language of Senegal. The second name means strong and determined in Swahili. Sankofa means ‘return and get it’ in Adinkra, the language of Ghana. The work wants to correct the image that many still have of Africans. It is a sort of call to dare to be different, with respect for the past, and to free yourself from the common, distorted representation of the African. Adjovi does that with beautiful, dark, refinedly lit, mysterious photographs that seduce as much as intrigue. A hand-written text tells the poetic story on a kind of blackboard. An international jury gave her the big Senghor prize at the opening. Justly.

Ndidi Dike (UK, 1960)

Mano Labor (2017) is an installation consisting of a number of cream-colored, tulle ‘cloths’ that hang on a rust-red sand floor on which objects have been placed that refer to those Congolese products with which the Belgian rulers managed to enrich themselves for years: diamonds and rubber. A poetic visualization of a bad past. Because the work is susceptible to air movements, it is precisely because of this that it draws attention to itself

Angela Franklin-Fay (USA)

Franklin-Faye shows that the American quilt tradition goes much further than making colorful bedspreads with geometric patterns. Especially for black American women it is and was a medium to comment on social situations, to make political statements. Famous are the textile works by Faith Ringgold who has been serving the ‘black case’ for more than 50 years with her narrative quilts. The works of Franklin-Faye – like Alized, 2017 – look like colorful illustrations of short stories, but if you look closer you see the references to a past that should not be forgotten.

Bathélémy Toguo (Cameroon, 1967)

A Book is my Hope, 2018

Toguo surprises in the Off program with an installation in a large bookstore. He brings an overwhelming ode to the book. In the center of the work is a large book composed of his own works on paper. From the ridge of the store, from a silhouette of the artist, dozens of books hang down, as if the artist serves marionettes. Around it are metal boxes where the books bulge. The floor is sprinkled with graphite. Between the books you see works by black thinkers and writers who played an important role. The book can hardly sell itself better. Toguo shows once again how well he manages to visualize an important message. And how naturally he manages to incorporate the environment, the space, into his installations.

Januário Jano (Angola, 1979)

Ambundulandu, 2017, © the artist

In a series of photos, presented as a block, Jano presents the rituals that healers or exorcists use in the Angolan Bantu community to activate spiritual powers. Wanted or unwillingly, he surrounds them with a haze of secrecy by placing the almost invisible protagonist in an earthly dark environment. Because the photos are also small, he forces the viewer to come closer and to look closely.

Moshekwa Langa (South Africa, 1975)

In KAM (2018) there are hundreds of objects on the floor that in one way or another play a role or have played a role in the artist’s life. An autobiography in object form. A huge jigsaw puzzle for the viewer who seeks guidance in the apparent chaos of bottles, books, threads, toys, records, mobile phones etc. On the walls are mostly abstract works on paper or collages that create balance, which serve as reflection material, that encourage you to mirror. An impressive whole.

Paul Alden Mvoutoukoulou (DR Congo, 1987)

Urgences, 2017

The artist has recreated the emergency room of a hospital. On the wall, persons who are waiting for treatment, a patient on the treatment bed. Literally flattened. A huge, threatening clock above his head. This sounds like a simple, somewhat kitschy story, but the quality is in the execution and the associated underlying meaning. All parts of the installation are depicted with dump material: used medications, capsules, packs and cartons. Mvoutoukoulou not only denounces the care, he also criticizes the throw-away industry and the consumer behavior that forms the basis for this.

Olanrewaju Tejuoso (Nigeria, 1974)

Wallsculpture, 2018

The wall sculpture of Tejuoso is overwhelmingly impressive. It gives a second life to waste in an almost festive way. On a surface of a many meters long and a few meters high ‘band’ of blackened pieces of wood, he places – in the center – in colorful red fabrics wrapped, irregularly shaped branches. To this he hangs ragged remains of fabrics. He sticks them, apparently randomly, also between the black burned pieces of wood. Accents with appeal. The red painted background – referring to the theme of the biennial – seems to hold the whole together.

Geraldine Tobe (DR Congo, 1992)

From the Mutumande Series, 2018

A series of biographical paintings, mostly executed in black and white. She does not paint with paint, but with fire, flames and smoke, referring to a dramatic accident with fire of which she was the victim during the shooting of a film. That event also explains the dramatic and sometimes frightening expression of which she provides her figures. She lifts her work out of the anecdotal because smoke can also be seen as a symbol for purification and incineration. The women in her work are ultimately liberated women.

Guy Wouete (Cameroon, 1980)

Democratic Classroom, 2016

A classroom with chairs looks out on a blackboard. On the board the text ‘Fragile, but not made in China’. A mysterious whole. A class without students and teacher. At the back of each chair hangs a text that symbolizes the character of the person who could sit on that chair. The variety is large. The teacher’s absence could indicate a decisive contribution from the students. They do not need a teacher. Does the class symbolize a society that craves for a dictator-less country with a large contribution from the population? For a country like most African countries are not?

Piniang (Senegal, 1976)

Photo: Javier Acebal

In a small Off-exhibition in the residence of the Dutch ambassador, work can be seen of Piniang. Paintings made in gloomy colors in which texts, figurative elements and abstract forms come together. Despite the dark colors, playfulness and irony are not lacking. The texts and the symbolic visual language make it clear that power, but especially abuse of power, is the decisive theme. The same people are always the victims of this. The Banlieues of Dakar provide convincing evidence.

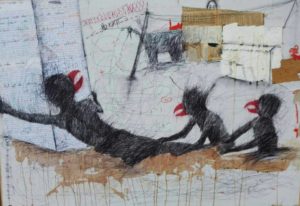

Ibrahima Dieye (Senegal)

From the Polysemie Series, 2017.

In the loose, sketchy drawings of the young Dieye, abuse of power also plays a major role. In a number of them he refers to those parts of the city – the banlieues – that are always flooded after heavy rainfall. The government pays no attention to this, let alone that it comes up with structural plans to combat the effects of climate change. The government is not interested in the victims. They are treated like animals and, in the eyes of the artist, they behave accordingly. Dieye tells his story by, as a collage, bringing together separate elements and different styles on one surface. Painted or drawn, for him these are interchangeable forms of expression. A great talent.

Raw Material

This institution has for years been the intellectual conscience of art in Senegal, and beyond. By organizing symposiums and lectures and by putting together small exhibitions, they make necessary connections with history and respond to the current discourse. This time, they presented non-European magazines, through projections and (spoken) sound, that played a role in revolutions or revolutionary moments in history from the end of the 18th century on. An intrusive, informative presentation that calls into question the alleged European hegemony.

3.

The exhibitions of the guest curators are a valuable addition to the whole. Even if only because they underline the importance of the past, of the African history. The country pavilions are unnecessary. Probably the organization has concluded deals with Rwanda and Tunisia in exchange for these public-relations-presentations. Most Off-presentations have a high degree of redundancy. A stricter selection would be useful, but also contradictory: they often arose to give a platform to those artists who were not selected for the main event.

4.

As was often the case with its predecessors, the role of social developments is very much apparent in the works of the participating artists of Dak’Art 2018. There is no lack of sensible content. Fortunately that does not lead to pamphletistic art. It is precisely the power of a lot of contemporary African art that content and form are integrated.

The Dak’Art remains a biennial that counts.