The failures of this show are not immediately in the works, but how the curators chose to conceive it. The short-circuiting and catch-phrasing stunts that have come to typify curatorial practice are slowly leading towards sterility. But if we look beyond the show’s slightly unimaginative presentation, Mlangeni’s images intimately and charmingly indicate a complexity in the Zion church, a complexity only a caring artist has.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja on the South African photographer Sabelo Mlangeni

Sabelo Mlangeni’s Umlindelo Wamakholwa

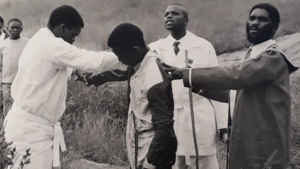

Umlindelo Wamakholwa is photographer Sabelo Mlangeni’s solo show at the Wits Art Museum. The show is mainly composed of a video and photographic works that are accompanied by a few contextually specific props linked to the show’s subject matter: the Zion church. The Zionist faith is Pentecostal, meaning its practices include speaking in tongues, purification, healing, baptism and so on. Its exegetical emphasis on Zion, greatly characterizes the anticipatory longing for “place” that is central to the Ethiopian movement. It’s a product, therefore, of the separatist tradition that precedes it, as it is also that of a spatial displacement engendered by the native land act. But importantly, the echoes of this background can be felt and seen in their liturgical practices which are based on combining African traditional practices and the Christian faith.

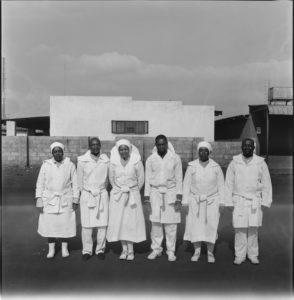

From their choice of white ankle-length garments, to even how some keep their hair and beard unshaven, to uses of traditionally premises wrists and waist bends, speaks of a sartorial inclination that is politically charged and also theologically ambivalent. The term “umlindelo” might, in a religious context, refer to all-night vigils held by the church as forms of collective worship. However, it could also invoke waiting as a social anticipation for change. A waiting for salvation and also for atonement.

Mlangeni’s photographs – both in black and white, and in partial color – are a delicate documentation of this prospective and anticipatory practice in the contemporary. Perhaps this pursuit for light amongst amazayoni can also, in a rather distant way, tell us about a theology of photography in South Africa, and more so its pursuit for revelation of the hidden truths of the everyday. Mlangeni in this sense, forms part of this lineage that has looked through the vapid and beguiling strife of everyday life, with lyrical and disorienting power.

Umlindelo Wa Makholwa (The Night Vigil of the Believers) curated by Kabelo Malatsie and Joel Cabrita, could invoke this possibility. The curators’ strategy (if that’s what it is) instead of choosing to display these works on typically white walls, they, recomposed the spatial look of the exhibition space to resemble or conjure up the church. In a gesture of inversion, the gallery’s walls are painted in the blue and white hues of the church’s palette; normally featured on its facades. Upon the entrance, a long blue sheet with a star-like emblem at its centre, hangs, bracketing the inside and outside. At the back of a dividing board which cuts the space in half, a couple of wooden staffs (used for religious purposes are clumsily placed at a corner where the board angularly bends. At the rear end, a video projection of a church session with a resounding religious riff furnishes the exhibition’s aura, that by giving it the aura of a church in progress.

I suppose, behind this mise-en-scene is an attempt to capture, for the audience, a kind of interiority. Yet this simulacral habit, arguably, pervasive in museum displays, unfortunately isn’t a gesture of critique of institutional methods but a means of uncritical re-inscription. Though relatively pleasant and atmospheric, in parts, it seems, its aim is to be instructional and nativistic. Furthermore, we’ve seen an escalation of what Hal Foster calls “ethnographic self-fashioning” in art, especially performance art, crystallizing and renewing itself into a method. Under the pretext of decolonization or alternative systems, a voguish turn to “the traditional” has usurped exhibition displays, turning them into quasi-ritual sites, where even white supremacy is deodorized under the fumes of impepho (incense). Far more than being enabling stimulants for a critical participation, they enable sycophancy and alterity in art spaces.

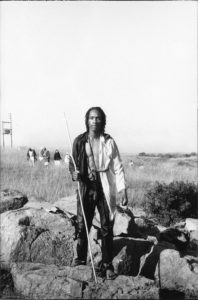

If we momentarily suspend or overlook this implied aura, and think a bit about Mlangeni’s pictures, what do we see? Perhaps far more than drawing our attention to the ever pervasive uniformed figures roaming the streets of Johannesburg or in their liturgies – something we can unanimously accept as being a cliché – Umlindelo includes an array of normally inconspicuous moments. There’s no particular sequence or order in which we are obliged to read these images. The portraits (of individuals or groups) are punctuated by images of religious props, tents, someone’s kitchenware, portable lavatories, and so on, in ways that are not so didactic. Take some of his portraits for example: whether of groups or individuals, the images rarely give off an ecclesiastical atmosphere. As items of religious importance, their tunics are not just well crafted and diverse, they are crisp and snazzy. They appear, in relatively secluded contexts, elusive and decontextualized even. We see them in the streets, in backyards, in their homes, under trees, etcetera but never diminishing beneath their religious structures, or signs. By virtue of this latent displacement, these images, arguably, are reminiscent of a serial aesthetic trope that dominates black-family albums. They are ordinary, yet also elusive and extraordinary.

This elusiveness becomes heightened by the images captured in motion, whose furtive presence could only be conjured as spirits or illusions of christological ascension. These flickers of evanescent bodies moving spectrally in the frame, instantiate, if you like, a quasi-theology of the photograph’s marking of presence. Far more than enticing our familiarity or curiosity, Mlangeni’s fugitive figures present a mystery or forms of anti-portraiture. The “portraits” of blurred or erased faces, or even those literally burned by exposure light, dramatize this disinclination. Light here, mystifies. In other instances, though, it beautifies. The latter is especially evident in how it bathes the seated priest in a fluorescent white uniform, giving him an anthropomorphic aura. It’s also seen in how it exquisitely ignites the albino child’s squinting face with abstracting illuminance. Mlangeni constructs figures with mythic presence like the priest standing half way in the water.

Between his rather elastic documentation and his sensitive portrayals, there’s no clear way of making sense of what the images tell us. We see ordinary things and even ordinary people, without being pointed to a scandal. We drift and wonder with them. For example, the image of sangoma-like figure walking away from the viewer with a chicken (held by its neck) in one hand and a knife in the other, we already know the fate of that chicken. Yet suspense kicks in because one wonders about the narrative that necessitates the sacrifice, as about the ritual event itself – the music and the chanting that is crucial to their forms of worship. So we see him or her once and never again.

If the objective of ethnography is to give us a comprehensive and pristine picture of its subject, these images don’t quite appear that formulaic. Instead, Umlindelo wa Makholwa steers us into a different direction, an elsewhere. The failures of this show are not immediately in the works, but how the curators chose to conceive it. The short-circuiting and catch-phrasing stunts that have come to typify curatorial practice are slowly leading towards sterility. But if we look beyond the show’s slightly unimaginative presentation, Mlangeni’s images intimately and charmingly indicate a complexity in the Zion church, a complexity only a caring artist has. These are as much an eclectic ensemble of pictures of the inner worlds of amazayoni as they are also benign snaps of a black everydayness. This religious community is not conceived as research or curricular object, but warm-blooded people with a liturgical life that goes back over a hundred years.