The Harlem Renaissance was a revival of black culture in a black district of New York. Yet there was a white critic, writer and photographer who had a great influence on the effectuation of that wave of creativity and pride. That was Carl van Vechten. He was appreciated and hated. He brought black writers into contact with white lenders and publishers so that their books could be published. He himself wrote a novel, Nigger Heaven, which for his title and his insight in the decadent nightlife of Harlem was filleted by many Harlemites.

In this article Rob Perrée gives a portrait of this controversial dandy.

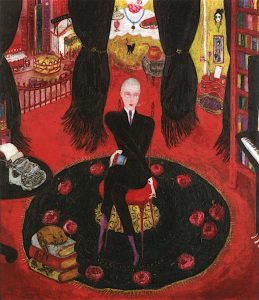

Portrait of Van Vechten by Florine Stettheimer (1922)

First published: Nov 1 2018. Because of the Harlem Renaissance exhibtion in The Met in New York we publish this essay again.

The Harlem Renaissance at 100

Carl van Vechten

Journalist, novelist, photographer and mediator

The historian and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois called the book “an affront to the hospitality of black folk and to the intelligence of white” and also “a blow in the face”. The poet County Cullen “turned white with rage” when he heard about the book. A critic condemned in his view the negative image that the book would create: Van Vechten sees the black community in Harlem “as dripping in sex and drugs and violence”. In Boston, the sale of the novel was banned. Ralph Ellison – author of the famous ‘Invisible Man’ – claimed much later that the book had introduced an unnecessary dose of decadence in African-American literature. The historian David Levering Lewis – specialized in the Harlem Renaissance – called it “a colossal fraud” in 1981.

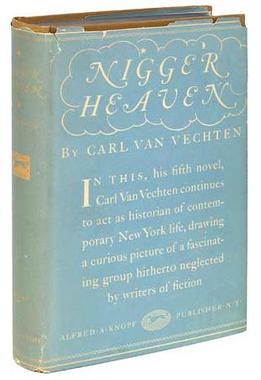

Nigger Heaven, 1926, original cover

The publication in 1926 of Van Vechten’s novel ‘Nigger Heaven‘ created a lot of uproar, to put it mildly. A book written by a white dance and music critic of the New York Times and Vanity Fair with such a title could hardly be received otherwise. Most critics fell on the title and never read the book. The irony escaped them. They did not know that the author was referring to the slang word for the segregated balcony in theaters, bad seats reserved for blacks. The downstairs room was reserved for white theater enthusiasts. So, the title was a reference that just points to the opposite of racism.

The position of Carl van Vechten within the Harlem Renaissance is not easy to explain. The reception of ‘Nigger Heaven‘ illustrates that.

Van Vechten was born in 1880 in Cedar Rapids, a then still small city in Iowa, in the so-called Mid-West. His father had a successful business and played a role in the local community. He sat in boards of clubs and unions and set up a school for black pupils. His mother was committed to the rights of blacks. According to the biographer of Van Vechten –( Edward White) – the family was of Dutch origin. In 1638 they emigrated from the island Texel to the US.

In 1900 he attended the University of Chicago. He was already familiar with the black nightlife there. One could often find him in the ‘Black Belt’. He worked for a newspaper that had as a starting point that a good story was more important than the full truth. An ideal school for a novelist, less for a critical journalist.

Carl van Vechten. Photographer unknown

In 1906 he went to live in New York, which was his wish from an early age.

He was a dandy-like, tall white man with a special, somewhat archaic language. A carnation in his buttonhole. Always “one step ahead of boredom and averse to taking responsibility (1). “He wanted to see the world.” (1) Those in his environment often got irritated by his mannerism. He soon became assistant dance and music critic of the New York Times. In 1907 he went to Paris to study opera. When he returned after barely a year, he became the regular dance and music critic of the newspaper.

There was nothing to indicate at that time that he was interested in what was going on in Harlem. On the contrary, he profiled himself as a somewhat arrogant, culturally conscious, white intellectual. Flamboyant, contrarian and provocative. In the first years, Greenwich Village was his favorite neighborhood. That was where the intellect and the theater world lived.

With his experienced nose for news, he gradually discovered that certain developments took place in Harlem where the rest of the US was not yet ready. The cultural revival there was unexpected and unprecedented. As someone who was not averse to attention, someone who was inclined to choose what the white elite found vulgar, he knew he had to be there, that he had to be part of it. That and the exciting nightlife of Harlem – the music, the parties, the cabarets, the dance culture – made him a regular visitor. “His diaries read as a guide to attractions in the city” (1) It was not unimportant, even though it was rarely explicitly said about him, that as a married homosexual he must have felt freer in an environment in which the boundaries were shifted and the cultural revival was often celebrated exuberantly. “(…) his string of sexual relationships with men (…) were an open secret during his life” (1)

Langston Hughes and Zola Neale Hurston by Carl van Vechten, 1939/1935

Conversely, Harlem was also interested in him: the young Renaissancists could use his many contacts and relationships well. For example, he managed to link the emerging writers and poets to white publishers. Without his intervention many books would never have been published. He helped many artists and writers to materialize their work. He taught them the importance of publicity and money. Later he would photograph almost all artists who played a role in the Harlem Renaissance. Until today, these photographs pop up in most of the articles about that special period in black history.

He built up a long-term relationship with a number of artists. With Langston Hughes for example. Despite their difference in origin (poverty versus material comfort), in age (more than 20 years), in their conception of what art should be (committed versus entertaining), they corresponded for almost forty years, about anything and everything. Quibbling, but also with interest and respect for each other and from a solid common basis of love for art. Hughes had the guts to defend ‘Nigger Heaven’ publicly. Not to flatter his friend, but because he really found it an important book and understood and respected the author’s motives.

For many Harlemites Van Vechten remained one of those many whites who enjoyed themselves in clubs where blacks could only enter as serving personnel, where they were treated as “amusing animals in a zoo”. The white “interest in black culture lasted only after the bartenders’ last call”, as Hughes once formulated it delicately. An understandable view, but a view that Van Vechten does scant justice to.

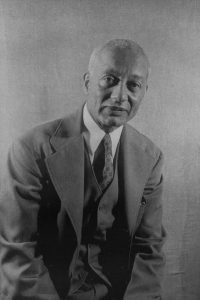

Alain Locke and Ethel Waters, by Carl van Vechten, 1941/1932

He started as an insignificant journalist with a local newspaper, then worked as a leading critic and then as a novelist, in 1932 he took another step. He felt that he had been written out. He lacked inspiration for another high-profile novel. Interest in his books also declined. He needed a new medium to satisfy his curiosity and his voyeur tendencies. Through a friend he got a Leica camera in his hands. That became the beginning of his career as a portrait photographer.

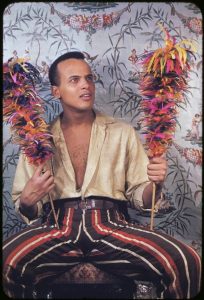

His first portraits were experiments. Promising but not good. He soon developed a more personal style. Gabel calls that the portrait-on-the-back-of-a-book style. At that place they would indeed not make a bad impression, but they are done more justice by placing them within the tradition of studio photography. The models are always placed against an artificial background of curtains, cloths or decorative wallpaper. Often objects have been added that fit the photographed. Almost all of them look sideways in the camera. They are all well dressed, probably for the occasion. Usually the look is serious. In a few cases he deviates emphatically from this (the series with Harry Belafonte is almost hilarious). The quality is in the intimacy that radiates from most portraits. That has to do with the fact that he knew his ‘models’ and that there was friendship or respect. He was not intimidated by his models and they were not intimidated by him. He got everyone who played a role in the black community in front of the camera: writers, artists, singers, musicians, dancers, movie stars etc. Because his studio was in his house, it meant that he received all those people at his home. That was certainly striking in the early years, because white people who received blacks were an exception to be criticized.

Harry Belafonte and Paul Robeson and Geoffrey Holder, ny, 1933, 1954, all Carl van Vechten

He did not photograph to publish the portraits in newspapers or magazines, but he did exhibit them.

That he also made nude photographs in addition to these portraits was only known in a small circle. In his will, he recorded that they could only be revealed long after his death. His homosexuality might then be a known secret and his interest in the black culture should not be doubted, nude photographs of mostly black men would certainly stir up the doubts about his intentions that already existed about him, even though his photos are more prudish than erotic. Moreover, they are usually so stylized that the intimacy that makes his other portraits so interesting is completely absent. He would never had become a George Platt Lynes – a contemporary, famous for his homoerotic photographic work. Van Vechten’s nudes were too cliché for that.

Was Van Vechten a great writer? Not really. Was Van Vechten a great photographer? Not really. He was a driving force of and in an important period in the cultural history of black America. His contacts and mediations made it possible for a number of writers to make their talents accessible to a large audience. His photographs literally gave a face to almost all the protagonists of the Harlem Renaissance. They found a useful way in many publications about that cultural revival. The fact that he wanted and was allowed to play a role in that important moment of time was exceptional. The interest in the Harlem Renaissance was extremely small in white circles. Even until today.

It did not go much further than the last call of the bartender.

-

Edward White, The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014).