A typical example of contemporary censorship under democracy was enacted by South African curators, students and art-world activists in Cape Town, featuring the burning of around 75 paintings, including ”Hovering Dog” by South African poet, visual artist and veteran anti-Apartheid dissident Breyten Breytenbach on the Cape Town University Campus in February 2016.

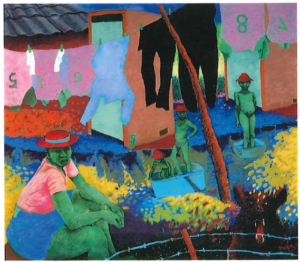

One of the censorship cases Argentinean-Arubian artist, poet, writer Arturo Desimone talks about in this essay

A Passerby, by Zwelethu Mthethwa (see links at the bottom of the essay)

Artists and curators must oppose the censorship of art in Western, Eastern and Global South societies.

“Where they burn books, they will also ultimately burn people”

-Heinrich Heine, 1821 (Quoted by South African journalist Geoff Siffrin in response to the 2016 Cape Town University art-bonfire.)

As an experiment, try putting the keyword “censorship’’ into the search-bar of E-Flux, the contemporary art world’s most influential publication among curators and artists (though other publications count more collectors among their readers.) Most search-results for keyword “censorship’’ deliver myriad mentions tagging Cuba, among other shadowy, far-flung regimes, and no Western democracy.

Boards of censorship often get called by their names in countries like Iran or Sudan, by those brave whisperers who question the official narrative, and especially by the murmuring artists and writers who must elude powerful bureaucrats for whom human blood runs as water. In Western democracies, however, those at the forefront of censorship favor entirely different terminology. Often, in “the affluent West,’’ censors happen to be accomplished academics, artists, curators and belleletrists.

Our liberal art-world keeps discussing contemporary censorship as if it represents an Asiatic problem. Though usually going by another name, censorship rears its head often in 21st century Western democracies. It affects affluent Western countries that enjoyed a longer “democratic experience” as well as the younger democracies in the ex-colonies that make up the Global South. In these contexts, the old force of censorship adopts a hypermodern, mystifying mask. Our censors demand different, new terminology to rename the same censoring act. ”De-platforming” as a term became popular after American feminist groups first coined it on campuses decades earlier. “Contextualization’’, like “explanation’’ are favored by authoritarian state spokespersons as well as by Human Resources departments and Museum-activists. “Safe space” (security matters) among other terms are in-famous and in-vogue of late.

When genitals were removed, like some gangrene to be scraped from posters of Austrian painter Egon Schiele’s “Girl in Orange Stockings’’ and “Self-Portrait Nude’’ in London in 2017, surprisingly few art-world opinion makers cried out in solidarity with the dead artist who was also blacklisted in 1930s Germany for “degenerate art’’. (If that surprises you, it’s a sign you’re no insider in contemporary art.)

Balthus, Thérese Dreaming (1938), installation view Metropolitan Museum, 2017

That same year, New York businesswoman Mia Merrill published her petition demanding removal of Balthus’ painting ”Thérèse Dreaming” from the Metropolitan museum, and demanded a ”corrective text” to ”contextualize” the painting lest it spark sexually harassing behavior among those who corporate-feminist Merrill refers to as ”the masses” in her pamphlet. Merrill’s petition to remove the offending painting from the inner city, added a finishing touch to the long-going sanitization and tidying of the city: that trend often called out by the popular, yet mystifying moniker of “gentrification’’. Doubtlessly, many of the activists who protest inner city sanitization still support petitions and actions like Merrill’s, while demanding “trigger warnings’’ on books, and “safe-space’’ asylums for all.

*

Gentrification, a sanitary project, is often reductively explained on the Left as either symptomatic of race relations, or a purely economic trend, originating in free-market neoliberalism; or both of these simultaneously. Seldom do such critiques explore the culture that accompanies “gentrification”, the morality of “gentrification”. Such a sanitary project is, of course, human activity, spearheaded by certain consumer-groups and individuals with specific ideas, lifestyles and values, who want a “Neo-Victorian” aesthetics for their surroundings.

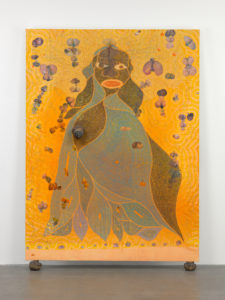

Chris Ofili, Holy Virgin Mary, 1996, courtesy David Zwerner Gallery, New York

A call for tidiness and public morality, demanded by affluent careerists, forms a fundamental part of the process oft-denounced as “gentrification of the city.’’ And apparently, hip patrons of the arts no longer need right-wing Catholic reactionaries like Rudy Giuliani to censor offensive art. As New York mayor, Guiliani in 1999 infamously demanded the removal of Trinidadian artist Chris Ophili’s icon of “The Holy Virgin Mary” from a museum, because the frame uses elephant-dung as a material. Today, those calling for the removal of offending works are more like Merrill: young professionals, self-identified political progressives, secular, and often boasting an academic background in arts and humanities.

The petition to scrap Balthus was by no means coincidental or unrelated to “gentrification.” The meritocracy of high-level corporate employees and entrepreneurs demands a place for them, catering to their whims, carved out at the heart of the urban center as if it were the docile suburbs. The contemporary culture of work has erased any barriers in time and space between work and leisure, as well as between suburbia and corporate offices in skyscrapers. The pristine surroundings of high-level corporate auditing bureaucrats ought, therefore, to reflect those values that helped them rise up the socioeconomic ladder. They dictate the contents of a national museum and of the sidewalks–free from miscreants and graffiti–as if these were their living rooms, and they were picking out matching curtains.

*

Consider an older petition for removal of a degenerate less fortunate than Balthus: in 19th century Arles, France, thousands of respectable townspeople decided to “gentrify’’, and signed a petition to have the drifter and unbearable, stinking nuisance Vincent Van Gogh banned from the city of Arles where he made his “so-called art works’’ when not harassing harlots. The 21st century revival of 19th economic trends has proven inextricable from the resurrection of dated 19th century morality.

*

Indirect boosts of support for the would-be iconoclast came from prominent voices in the curatorial sphere, including Thomas Micchelli, who writes catalogue essays for international museums and co-edited numerous books on curating.

In HyperallergicWeekend, Micchelli decries “a half-naked teenage girl is key not only to the uncomfortable critical reception to his show at the Met, but to his awkward place in the modernist canon’’ further underlining “the trashiness in the artist’s backward mindset’’ [2] Thomas Michelli’s screed, echoing Merrill, makes “backwardness’’ key: who defines the Zeitgeist, the spirit of our times? What is backward; who determines the Great March Forwards in our values? Curators are competing to take rank among manufacturers of the ruling values, designers of the canon, and the love of art does not figure as a priority. Any mention of “love for art’’ sounds contemptuous, trivial, conservative to the enlightened, who seem bored by their access to high culture because they always had it.

*

Tellingly, women writing for Frieze came to the defense of ‘’Therese Dreaming’’ against the puerile iconoclasm defended by Michelli who writes of concern for “underage sensuality’’ apparently off-limits for artists. The fashion of “male feminists’’, men who express outrage in solidarity with radical feminism, has led to a disturbing trend that reopens the backdoor to conservative attitudes in the name of “respect for women.’’ People who come from conservative societies can more intuitively understand the dangers of such piousness when it emerges in the parochial disguise of ‘’respect for women’’’ in solidarity with the censorious radical feminism that has become a Sine Qua Non in the art fields. When I was receiving my colonial education in a small, conservative Catholic Caribbean island village–Aruba– school-teachers sought to punish me, or removed by drawing materials in the name of “respect for women’’ when they found my drawings of nudes. Conservatives would implore respect for “our sisters, mothers, daughters’’ at the sight of nudes.

*

Many artists and thinkers who hail from conservative societies at the margins, move to Western centers of the art-world only to encounter a breed of young and blasé metropolitan intellectuals who have decided that prudishness and domesticity to be both “radical chic’’ and the social norm for their generation and thereafter. The fad is not fading.

John William Waterhouse, Hylas and the Nymphs, 1896

Similar to the support of puerile iconoclasm in New York, around that time in England, curator Claire Gannaway justified the removal of “Hylas and the Nymphs’’ an erotic Pre-Raphaelite painting by John William Waterhouse from the Manchester Art Gallery, calling its presence ‘’outdated and damaging.’’

*

The prissiness of censors in Western modern contexts obviously represents less danger than a Joseph Stalin or a Jorge Rafael Videla. Focus-groups behave like irate customers, confident that under Capitalism, Customer is always right—if a product offends, let it be pulled from the shelf. Pulled is in fact the preferred word to substitute “censorship’’ among activists: a defective line of products can be pulled, a (shelf) article can be pulled. Pulled offends less.

But what happens when the sculptor from Sudan, who cannot exhibit sculptures revealing the female nude in his country, suddenly discovers he cannot exhibit these in Western democracies either?

Dana Schutz, Open Casket, 2017

An artists’ collective led by British artist Hannah Black at the Whitney Biennial insisted ”censorship” was an unfair description for their demanding the public burning of a painting, ”Open Casket” by Dana Schutz, in 2017. The painting had to burn, according to their online petition, to punish a white artist for depicting a historical scene of murdered black youth Emmett Till.

*

Activists all but ignored Californian painter Henri Taylor, whose paintings at the biennale depicted contemporary tragedies of police shootings. Curated group exhibitions often show works of different artists, different materials and styles, treating the same theme from varied angles and experiences. Such a petition, representing an attack on curatorship itself, met virtually no opposition from curators Christopher Lew and Mia Locks.

*

Curators, in most of these situations, come across as embarrassed, reluctant, and fearful to defy the angry pressure-groups. If curators want to justify their prestige as conservators, critics and preservers of culture, can they afford to be such pansies when the time comes to defend art? Can a curatorship be called successful by any measure, once the curator backtracks from defending choices made, the “offending’’ selected art and artistic statements?

*

Vanguards of 1920s Europe, like the Futurists and Surrealists, welcomed expressions of rage and hysteria from audiences. Italian Futurist curator Marinetti famously propped sledgehammers next to Futurist works on opening night, perhaps originating the first interactive installation. Thusly the Futurists, who politically favored the radical Right because of its irrationalism and adoration of technology, began a Fascist tradition of allowing enraged consumers to destroy the offending products.

*

Futurist and Surrealist artists and manifesto-writers welcomed such responses of hatred head-on. After the glibness and pollyanna that lured Europeans into World War 1, vanguard artists sought to evoke emotional extremes in their audiences. Avant-gardes of yesteryear defended their right to infuriate. Accepting the consequences, they stuck to their guns.

No right seems currently less presumed, more forsaken, today than the right of art to offend. Today’s curator aims for cerebral interactivity with the audience, perhaps evoking only those emotions that can be contained by pensive therapeutic consolation and placebo-politics. But they call the game when it goes too far for some audiences. Capitulation by the curator seems essential to this kind of censorship: typically the curators prioritize the will of an activist whistleblower, representing the specter of “Civil Society’’. In an era of utilitarianism, NGO activists stand as the victors of the financial battle to gain the attention and support of philanthropists; while art has lost out.

*

Today’s first world philanthropist donor sooner invests in NGOs, charities and good causes, no longer competing for the once-enviable aura of “patron of the arts.’’ Rather than defending the value of art, curators use the inoffensive language of NGOs, to try to convince the philanthropic class that investing in activistic art can be just like donating to a charitable cause.

*

Philosopher Ruwen Ogien defended the freedom to offend as essential to artistic creation. Curators who rather not come to the defense of that essential right to offend, should resign. Instead of public statements of resignation and of their failures, they upload apologies on behalf of the offending art-pieces. In his 1950s lecture-series “The Human Situation’’, Aldous Huxley correctly predicted the return of Right-wing demagoguery coinciding with a time of “political correctness’’ in art: the author of Brave New World told his St Barbara college audience that when the public can choose between glibness or hatred, hatred wins for its higher emotional dividend. In the long term, the glib apologetics of curators cannot abate the ire of arsonists.

*

Curiously, Huxley also praised European vanguard painters who learned from Polynesian and African art to depict emotional extremes in their work, reviving Western art through Non-Western influences–a process which today would be denounced for “cultural appropriation.’’

So why was contemporary censorship not more of a “hot topic’’ at any major art-world event recently?

Documenta 14’s curators invoked artistic freedom recently, when they came under attack for allegedly ”misspending” German money on Greece, a controversy that reflects the real ruling values of the investors behind Kassel’s mega-show of the well-intentioned. A mostly non-German team used German benefactors’ money, intended for Kassel, to throw a show in Greece—a small country at that time on the receiving-end of ire and blame from German political elites and media. Curators knew their freedom was at stake only when sponsors punished them, by smearing the Kassel team in the press for “corruption”. By lavishing money from the German Sparta onto indolent Balkan debtors, the mostly imported curators had violated a sacred trust, overstepping boundaries.

Ideally, curators at any institution have a background in art-history. Inevitably, they stay informed of contemporary censorship scandals in the museum world, such as the petition against ”Thérèse Dreaming’’; or the banning of Egon Schiele’s nudes from the London tube.[4]

Consumerism and work must go uninterrupted: ergo, London passengers on the Tube had to be spared any confrontation with the mortal beauty of Egon Schiele’s nudes ‘‘Girl with Orange Stockings” and ‘Self Portrait Nude” in posters removed by transport authorities and the mayor. Commuters underway between work and leisure must be fixated in their busy-ness, with no aesthetic or psychological upsets to the psyche; no derailment of routine responses.

Curators living under democracy, in a global art world, must use their knowledge and power to extend solidarity to the living and dead victims of such commonplace violation of artistic freedom. Yet they seem more eager to endorse censorship. They see no difference between saying “all art is political’’ or “all art must adhere to one political program.” Perhaps in a time when democracy is in recession everywhere, the reaction is to tell artists that they must produce art that can simulate democracy. All art is political; but doublespeak is not art.

The word “curator’’ implies custodianship, as well as the Latin meaning of “quarantine’’, “caretaking’’ “curing’’ the diseased: words that could serve as ambiguous metaphors, describing editing, acquiring and excluding works, preferably on the basis of aesthetic evaluations.

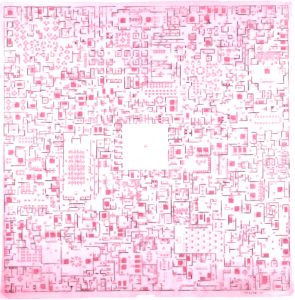

Léon Ferrari (not the one mentioned in the text)

In Buenos Aires in 2004, Catholic protestors stormed an exhibition in the Recoleta Cultural Center, using violent coercion demand the removal of a “blasphemous’’ piece by León Ferrari. Argentinean curator Andrea Giunta stood in defense of art, maintaining contact with police, the Church and city government, insisting on keeping the exhibition in place–no apologies.

*

If we no longer believe in aesthetics, then editorial choices can only be made on other grounds like saleability, usefulness, or morality. Curatorial choices based on saleability and usefulness lead to the confluence of fashion and the designer-accessories-market with art. Editorial choices that obey moralism, lead to censorship. But curators should not want the freedom to forsake any commitment to aesthetics, after having chosen art.

*

If the custodians and protectors of art won’t live up to their professional and ethical duties to protect art from moralistic violence, do we still need them as authorities? Have these schoolmasters learned from history? As Chomsky’s anarchist dictum goes If ruling elites cannot legitimize their existence, get rid of them.

Burning Art in the Southern Hemisphere

A typical example of contemporary censorship under democracy was enacted by South African curators, students and art-world activists in Cape Town, featuring the burning of around 75 paintings, including ”Hovering Dog” by South African poet, visual artist and veteran anti-Apartheid dissident Breyten Breytenbach on the Cape Town University Campus in February 2016. [5]

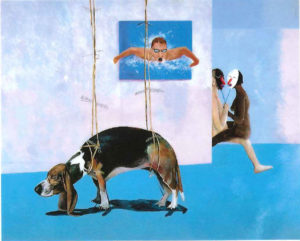

Breyten Breytenbach, Hovering Dog

The riots that led to burning of art works, rose in tandem with the ”#Rhodes must Fall” student movement, calling to have monuments built by colonial ideology removed from public view. To have Rhodes statues removed does not seem such an odd idea—usually, when a regime falls, monuments of the defeated regime can be assigned a new context, hopefully in a museum.

*

After the city Pretoria (named after colonist Andreis Pretorius) had its name officially changed under the ANC government to Tshwane in 2005 –much to the outrage of South African whites–it seems hardly radical to demand the moving of statues of historical colonizer Cecil Rhodes into, for example, a national history museum.

Strangely, the attacks targeted and burnt works by African contemporary artists who actually resisted Apartheid when they lived under its toppled tyranny.

*

During Apartheid, Breytenbach was put on trial for writing poems that offended Boer authorities, and did jail-time for supporting black uprising. One of JM Coetzee’s essays on censorship collected in “Giving Offense” recounts how white supremacists prosecuted Breytenbach for having asked, in Afrikaans-language verse, how a police commissioner could finger the pudenda of his wife with the same hand that had massacred black children.[7]

*

More recently, when the poet’s drawing titled ”Hovering Dog” was mentioned as one of the burnt artworks, in a document leaked to Ground Up magazine, Breytenbach joined David Goldblatt (sculptor of a destroyed work depicting an enslaved South African woman) and other artists who publicly stated that the University does not respect their rights under the South African democratic (post-Apartheid) Constitution. Poet and sculptor pleaded for all South African artists to withdraw their art from South African universities. CT University refused to answer to the press about the fires.

Wamuwi Mbao (anonymous photographer)

In response, a young art critic who supported the burning, Wamuwi Mbao, gave declarations invoking familiar jargon of the curatorial world, with a whiff of Foucault. Mbao complained of “an anachronistic panic compelled by the specter of censorship that tends to invite underthinking. Art is about meaning and audience. So it might be useful, if we’re to think about the difficult question of what constitutes censorship, to understand that censorship involves particular dynamics of power and control (through withholding) of information that has a particular configuration in the world. Removing a work of art from a room because its meaning is unsatisfactory to its audience isn’t censorship. It’s merely changing the configuration of that art in the world. It’s still there’’ even after being burnt.[6]

The language of the arsonist mirrors the language of contemporary curators. No accident there, for Mbao is an arts journalist, inhabiting the vague space generally understood as “contemporary curator.’’

*

A group of curators organizing an exhibition at Stellenbosch University celebrated Mbao’s defense of the bonfire, a text in which he also lambasts Breytenbach for having a Vietnamese wife (though under Apartheid that was a violation of racial laws) and for being “so boring’’ with his plea against art-burning. Mbao insists Breytenbach has become reactionary, pointing to the poet’s having earlier decried University plans to scrap Afrikaans-language studies. Afrikaans, a colonial Creole offshoot of Dutch, happens to be the language Breytenbach writes poetry in. So is Mbao serious, or just cajoling and bullying (with a smattering of Foucault to make the bullying sound intellectual)?

*

Little regard for the irony in how Breytenbach endured censorship and prison under Apartheid. Perhaps Mbao’s admission of boredom reveals one key motivating factor behind global iconoclastic pyromania: the jaded frustration of middle class ascendancy, the lethal ennui, a kind of boredom that French and Latin American maudit poets warned us of.

SA Arts writer Edward Tsumele denounced the Cape Town burnings as a violation of democracy and artistic freedom. When asked if art can be decolonized he told the press ‘‘Let the art prevail, colonial or not colonial. This is an expression of how certain artists interpreted what they saw at certain times in history. Let us as the public view everything” and added ”What I resent is for people to be offended on my behalf, and therefore try to think for me as to what art I must view as an adult. I should be allowed to be offended on my behalf, not have anyone else being offended for me.”

The fashion of progressives taking offense on behalf of another, at first seemed a first world problem, descriptive of neurotic positions assumed by censorious activists in wealthier countries. Incidents in Cape Town prove otherwise, though the activists behind the campus art-bonfire mostly counted middle class students.

Why were the incidents so eerily underreported outside South Africa? Exhibitions in the West documenting and using art about the #Rhodes must Fall movement, such as the show “Re(as)sisting Narratives in South Africa’’ in the famous FramerFramed contemporary art center in Amsterdam, made no mention of the burnings of contemporary paintings. The movement behind the bonfires played a protagonist’s role in the photography at the Amsterdam group exhibition shown in 2016 before it travelled to Cape Town. Some visitors attending the Amsterdam exhibition celebrated Mbao’s published justifications of the burnings on social media.

*

With Cape Town University, a familiar contemporary dynamic unfolded: faculty sides with student demagogues, refusing to enforce the law, let alone any function towards the preservation of knowledge or the intellectual duty to challenge preconceived notions that one outspoken group held to be self-evident.

*

The Cape Town burnings foreshadowed events at the Whitney the following year. The insistence by young artists that burning other artist’s work is a form of progressive activism, their negligence of history, and their ire when the word ”censorship” was used, recalled, however vaguely, the horrors of book-burning as the true poet Heinrich Heine foresaw them in his native Germany. In Cape Town, as in Manchester, in London and New York, a censorious lot insisted that their actions not be identified as censorship. Invoking the academic cultural theorists, they refused to take a stand by naming the action, the censorship they endorse. We must feel compelled to call it by another name of the censors’ choosing. Perhaps their obsession could be called “nominalism’’ the idea that everything is in a name.

This year saw two more colossal acts of arson. Río de Janeiro now has only the ashes of Brazil’s 200 year old Museum, which burnt down in September, with cultural and scientific heritage from Brazil and the world over, including some of the oldest human fossils, and Egyptian mummies collected by Brazil’s 19th century emperors, as well as recordings of extinct Amazonian languages.

Such fires are by no means a strictly “Southern’’ or third-world phenomenon: the Brazilian fire took place just four months after the summer arson that claimed the historic Glasgow Art Academy, an edifice designed by the Scottish architect Mackintosh.

*

In the face of these acts, we must respond to the brutal treatment of present and historical culture, with the same fervor and insistence that progressives tend to invoke to protect the imperiled ecology. Progressives believe in the urgency to protect ecology when scientific opinion indicates there is evidence to do so. We do not protect art history or artistic freedom the same way, not believing the worth of the impractical, of that for which there is no “data’’, no baggage of ciphers and no scientific opinion declaring its relevance. Although scientists themselves often benefit from art and culture, when they admit thusly, it suddenly no longer counts as ‘’scientific opinion’’ or ‘’evidence’’ for the value of art.

*

Rio’s National Museum burnt because of liberal economic policies sworn in by a coup parliament, which reduced the annual budget of maintenance for the centuries-old Museum to a sum of around 3000 dollars. The Cape Town arson had more numerous ideological causes, among them the transnational Zeitgeist on university campuses. Though the Brazilian fire was unintended as an act of censorship, the disregard for heritage and for a museum has the same origin as contemporary censorship: a violent consumerism, self-imposed amnesia and apathy that emerge in the Southern Hemisphere, mirroring what has long been afoot in the North’s successful capitalist societies. Meanwhile, the language of Foucault and post-structuralists, along with the more boring budgetary jargon of neo-liberal economists, have served in different contexts to justify passivity while bored bureaucrats feed art and art-history to the bonfire.

In all this darkness, where the defenders of art and culture?

*

Curators and artists are traditionally the preservers of culture. Curators and artists who today jeer, fashionably in favor of the burnings will, one day hopefully, have to answer for not having come to the defense of art.

[1] This essay is an adapted extraction of an earlier, unpublished essay by the author, “Parthenon of Silences”

[2] Showing Balthus at the Met isn’t about Voyeurism, it’s about the Right to Unsettle Laura Elkin, article. Dec 2017, Frieze Magazine Web.

[3] Grenier, Elizabeth Berlin College To Remove Mural Poem Deemed ”Sexist” article, January 25 Deutsche Welle web http://www.dw.com/en/berlin-college-to-remove-mural-poem-deemed-sexist/a-42300838?maca=en-Facebook-sharing

[4] Nella Londro del sindaco Sadiq Khan le Opere Schiele Tornano Blog post http://www.francoziliani.blog/2017/12/01/nella-londra-del-sindaco-sadiq-khan-le-opere-schiele-tornano-arte-degenerata/

[5] List of art-works destroyed or removed at Cape Town University in Ground Up Zimbabwean magazine Leaked document. Web https://www.groundup.org.za/article/here-list-art-destroyed-uct/

See also

https://arttimes.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Art-Under-Threat-at-University-of-Cape-Town-Dossier.pdf

[6] The removal of Art at UCT Interview in Litnet

[7] See JM Coetzee’s ”Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship” for commentary on trial against the poet

[8] Lit Net Interview. 2016 Web.

http://www.startribune.com/painting-of-philando-castile-s-death-on-display-in-new-york-s-whitney-museum/430375453/

https://frieze.com/article/showing-balthus-met-isnt-about-voyeurism-its-about-right-unsettle

https://www.groundup.org.za/article/here-list-art-destroyed-uct/