For Artur photography is about cultivating trust between the artist and the subject. Her focus is on representing people the way they want to be represented. Documenting that in a picture is a form of conservation and she has kept her lens on the Black community, focusing on the everyday moments that present themselves.

Christabel Johanson on Liz Johnson Artur

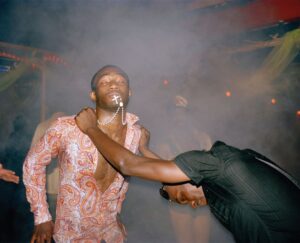

Untitled, 1996-2012, courtecy Brooklyn Museum, copyright Liz Johnson Artur

Liz Johnson Artur

Born to a Ghanaian father and a Russian mother, Liz Johnson Artur is one of a few “Afro-Russians” linked to the country. Many others came from Caribbean parents that had been offered free university education during the Cold War or had been raised in the country’s foster and care homes. Artur herself was born in Bulgaria, educated in Germany and is currently living in London. As an artist her life experiences have been international. Yet the question of identity is something which her work consistently seeks to explore. The African diaspora, particularly living in countries perceived as less tolerant to diversity, have not had a big enough platform or wide representation in media and popular culture.

*

Russia has a poor reputation for social issues including racism and marginalisation of people of colour. In recent years this was highlighted when the country faced several sporting controversies. This unexplored underbelly was partly the reason that inspired Artur to begin documenting Russians of Colour. From 2010 Artur’s photographic project has helped to increase representation of these minorities. She discovered that unlike the African-Americans or black British diaspora, many of her subjects did not have much exposure or access to their black heritage. Perhaps this is something second and third-generation immigrants to the Western world have taken for granted. There is a standard of integration for them that has already occurred over decades of socialisation. However for a country more closed off such as Russia, progress appears slower than other places.

*

As one of her subjects from Russians of Colour, George hailed from the Congo and later moved to St Petersburg having since had a child with a Russian woman. “Around 2004 there were a lot of attacks by skinheads in St Petersburg. After the death of an African student we organised a big demonstration in the city. I spoke at the rally and afterwards the FSB [Russian state security service] held me for two days, questioning me about my activities. But I don’t have any hard feelings: it takes time for attitudes to change.”

George runs a martial arts studio in St Petersburg

Gera describes his childhood as “not easy” but “I have always been proud of being black. Growing up I got a lot of attention, and a lot of it was not good. Russia is quite a chauvinistic country. They don’t like black people here.”

Gera in Moscow

Vlada lived in Moscow for seven years after travelling to different parts of the world including Spain and Brazil. She describes other places are “more friendly” than Russia. She describes Moscow as a “beautiful city, but people here can be quite hard, and very nosy. Strangers trying to touch my hair is something I really don’t like.”

Vlada (front) and her friends in Moscow’s Red Square

These subjects experienced the “typical” symptoms of a community that have not been fully integrated; making a spectacle of Afro hairstyles, negative attention from authorities, attacks from Fascist groups. Where a lot of racism in the West may now be understood through micro-aggressions, minorities at the fringes are experiencing hate crimes akin to the Windrush generation.

Artur now lives in South London; a space traditionally accepted as multicultural with Black, Asian, White and European inhabitants. Regarding her experiences growing up she accepts that she looked different to most people in Germany and internally there were times when she felt more Russian or more German. Artur did not meet another Afro-Russian until she was in her mid-twenties. However this isolation from others like her enabled Artur to see her identity as fluid; as an adaption of where the individual is in their current situation.

The photographer grew up with her white mother and did not meet her father until 2010. This encounter partly kickstarted her Russians of Colour project. It was a way of creatively getting closer to a side of herself she had not explored before. “The only way for me to understand why I took all these pictures…I was hungry but I didn’t know that I was…it’s like when you start eating…you realize how hungry you are and when it came down to pictures I now realize how hungry I was”.

For Artur photography is about cultivating trust between the artist and the subject. Her focus is on representing people the way they want to be represented. Documenting that in a picture is a form of conservation and she has kept her lens on the Black community, focusing on the everyday moments that present themselves.

Blackfriars Settlement, London is Love commissioned by Southbank Centre

However she has previously said that her work is not overly political but rather poses questions to ask the viewers. These questions are around the communities and people who occupy a particular space at a particular time. Her portfolio is like a travelogue over the decades. Here is Artur’s idea of fluidity again. She views her work – like herself – as uninhibited by any one identity. Russians of Colour can preserve the uncelebrated diversity of the Afro-Russians, it can also chart a period of time of a country, or it could be used as a marker for comparison in history. The fewer labels her work has, the more versatility it gains.

*

Her home contains boxes and boxes of prints accumulated over the years but she is mindful that her work makes cohesive sense rather than being an amalgamation of assorted images. Artur’s love of versatility can be found here too. She’s been quoted as saying that normality is a “luxury”, in part this is why she visits so many public places for inspiration. Over the years she has shot many photos of everyday normality. Likewise her work, she insists, focuses on humans who are more than just their background.

Yet there is still an overlap between her work and the Black diaspora she captures. Artur has said this is simply about representing people who aren’t seen anywhere else. As such her Black Balloon Archive has been growing for around three decades. The title is inspired by Syl Johnson whose song lyric mentions a black balloon “dancing” whilst it is in the sky, which is the symbolism Artur imagines when she is photographing. From time to time a collection of images from the archive will make their way into a show. For instance If you know the beginning, the end is no trouble was exhibited at the South London Gallery in 2019.

If you know the beginning, the end is no trouble, South London Gallery (2019), Photo: Andy Stagg

The gallery housed several bamboo screens structures of her prints, which were all shot through analogue photography. The artist wanted something natural and organic to bring people in. For the bamboo canes, Artur’s sculptor friend helped construct them for the show. From the handmade scaffolding to the traditional photography, there is a certain natural home-crafted feeling that runs through all her work.

In other words Artur’s work comes from the heart. The things that are important to her are connecting people, especially marginalised groups but capturing them in a wider context. Her subjects are not just black people, queer people or immigrants. They are humans whose unique experiences in those moments deserve recognition and celebration. They are more than the sum of their parts.