Iyabanda Intsimbi / The metal is cold, the South African artist Cinga Samson’s solo exhibition at the FLAG Art Foundation in New York, is composed of a series of (self)portraits and ‘private’ scenes that border on the ritual and funereal. Cinga’s portraits are pensive, sans pupil, cool and casual, confidently posing and adorned in gold. His dark palette of oils sinks his Black figures into ‘their’ world, threatening to disappear them into the Darkness that looms right behind

Vusi Nkomo on the Blackness of the works of Cinga Samson.

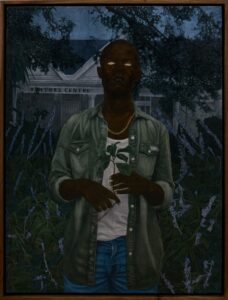

Ibhungane 9, 2020

Figuring Blackness

“Lest we think that this force [of the Middle Passage] is merely the grammar and ghosts of blacks in the “New” World, that somehow Africans of the twentieth and twenty-first century have an altogether different rebar of ontology, we should note Achille Mbembe’s argument that, once Hegel (as a placeholder for all the punishing discourse of the Maafa, or African Holocaust) renders Africa “territorium nullius,” “the land of motionless substance and of the blinding, joyful, and tragic disorder of creation,” even the African who was not captured was a slave in relation to the rest of the world, his or her freedom from chains and distance from the Middle Passage notwithstanding.”

Frank Wilderson III, GRAMMAR & GHOSTS: THE PERFORMATIVE LIMITS OF AFRICAN FREEDOM (2009: p. 122)(1)

“I was thinking why is life designed like this? Why is life designed with this flaw…this element that one is disposable?”

Cinga Samson, Iyabanda Intsimbi / The metal is cold (2021)(2)

How can we think productively about the relationship between Darkness and Blackness? In what ways does Dark(ness), both conceptually and chromatically, evoke Black(ness), and how does this push and pull between a descriptor, on the one hand, of light (little or lack of), and, on the other, a structural position occupied by the people known as Black, allow for a richer reading of contemporary society? If Blackness emerges, paradigmatically and historically, from the Dark (the continent, Africa), and as the ultimate Dark (pigment) both as subject of phobia and -philia, and both conceptions seem to have undergone no fundamental transformation until this day, what does that tell us about the modern World?

Installation View, Flag Art Foundation, New York, 2021, copyright Flag Art Foundation

lyabanda Intsimbi / The metal is cold, the South African artist Cinga Samson’s solo exhibition at the FLAG Art Foundation in New York, is composed of a series of (self)portraits and ‘private’ scenes that border on the ritual and funereal. Cinga’s portraits are pensive, sans pupil, cool and casual, confidently posing and adorned in gold. His dark palette of oils sinks his Black figures into ‘their’ world, threatening to disappear them into the Darkness that looms right behind. They stand solo, unmoved, in the middle of a world they are not obliged to pay attention to. These figures’ hands busy themselves with (decaying) flowers and cloths, holding these items up, covering (parts of) the sad and somber faces at times. These hands make no serious attempt to conceal the eyes; you are meant to see them, look at them as they are looking at you, with a cold and empty non-look. They offer no access to them (as objects of desire and signifiers of a particular perspective); one could argue that they refuse any access, throwing it back, or at least blocking or denying it. Considering the importance afforded the eye (as vision, so-called window to the soul, and a host of other ‘classical’ signifiers) in the Euro-Modern aesthetic and philosophical tradition, and how central this organ is to thought and knowledge production in the ‘New World’, it would be safe to safe, theirs is a dead perspective.

This dead perspective is the Darkness of this work/world that moves or transforms the dark(ness) of the paint(ings). I am thinking of the emptiness of the eyes as what I want to call an anti-ocular, an interdiction against the mode of seeing, which is to say, the privileging of looking over other senses (that are important for the purposes of, but not limited to, cognizing and feeling), which forms the bedrock of Euro-modernity, or simply, the World as an unethical epistemic arrangement. It disallows the ocularcentric function of the gaze, asking what would ‘aesthetic appreciation’ be not only without modes of seeing, but looking writ large. (I am however in no way arguing or proposing or prescribing an inversion of this mode of being as a political program that would ensure or usher us towards a new ethical epistemic order).

And so it is in this note that I’d like to return to my opening provocations and thoughts on pairing Blackness and Darkness, a tension that is already a function and in function in Cinga’s Iyabanda Intsimbi.

This body of work, or this work on the (Black) body, is confronted, or should I say, haunted by what already haunts these empty eyes/dead perspectives that Cinga painted: that Black bodies, I argue contentiously, have no gaze to return (which is incidentally, as I argued earlier, evidenced by the wiping out of the pupils) and that this perspective, even in its death, as per my argument, is as absolutely vulnerable and available for enjoyment as the bodies it inhabits. I seek to sustain this argument by looking towards the darkness of the explanatory gestures of the artist.

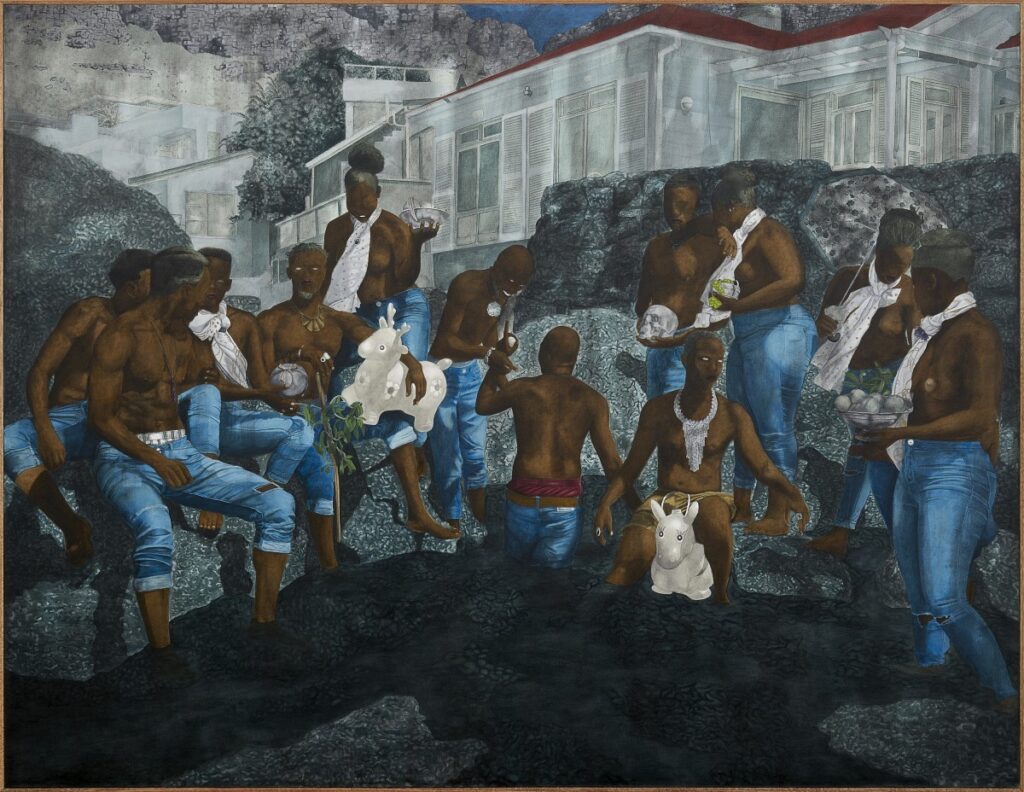

Umkhusana 1, 2021. Oil on canvas, 86 5/8 x 102 3/8 inches (220 x 260 cm). Photography by Steven Probert for Flag Art Foundation.

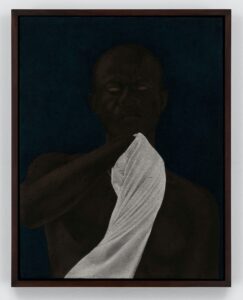

In Umkhusana 1 (2021), ‘umkhusane’, defined by Faxi-Lewis (2003) as a “white cloth used as a screen during a ritual ceremony made by diviners to conceal the ritual objects of an initiate,”(3) functions as a device to conceal, keep secret, or hide. The details of what is being hidden, kept secret (from us), is not important (to Cinga, and us) but the hiding. The hiding is the ritual and the object simultaneously. (Michael Taussig reminds us throughout Defacement: Public Secrecy and The Labor of the Negative(4), that there is nothing private about the secret). It is the something going on and we must look no further than ‘umkhusane’. What it conceals is not some piece of gossip tossed around in Cinga’s circles; it perplexes him too, and he says, trying to figure it out, “the nature of violence: its laws, its flair, and its finality”.

Umkhusana 2, 2021. Oil on canvas, 86 5/8 x 102 3/8 inches (220 x 260 cm). Photography by Steven Probert for Flag Art Foundation.

Izilo zomlambo 3, 2019 (Omenka Online)

The nature of violence. Where would we then situate or place Blackness in this gap between nature (not necessarily as real physical phenomena) and violence (the spectactular matrix and social phenomena)? How do we think of this violence, with Cinga, in relation to Black people and Blackness, a group that has or can claim violence as an essential grammar of suffering and structuring modality that paradigmatically positions them as Slaves in (relation to) the World? Is there a relationship between this motif of decaying nature and ‘disposable’ Blackness, ontologically speaking? Something like, proof of “[s]ubjects […] who are dead to the world [nature?] precisely because they are already dead [hidden by umkhusane], and whose aliveness only makes us aware of their being already dead [in relation to the World]”?(5) To complicate this crisis further, we can consider Cinga’s statement or hopes that he “wanted the feel of the show to be as though you’ve just stumbled upon a scene you weren’t supposed to see”; this wouldn’t be as difficult if Blackness wasn’t always already dead to whomever sees it, Hegel included. Blackness gathered around death in the Dark(ness) of Africa, territorium nullius, is exactly what was supposed to be seen in these scenes.

Cinga Samson, Lincede 4, 2021. Copyright Flag Art Foundation & artist

“Intsimbi ebandayo” (cold metal)”, writes Lwandile Fikeni(6), “signals the coming of death”. Considering our shared morbid fascination with the somatic qualities of Blackness, what else could it signal but this? What other capacity(7) can Blackness claim other than the problematic of “violence and captivity [as] the grammar and ghosts of our every gesture?”(8) As specific as Cinga’s study is, these paintings (and the explanatory gestures that accompany them) labor to clarify something more global and pervasive; Black death.