Today, the National Gallery of Zimbabwe displays birds made of trash and platforms artists who revel in the rubbish heap. This is by no means a decline in sculptural quality, and I don’t intend to deprecate the curatorial work happening at NGZ either.

Rory Tsapayi on the role of trash in Zimbabwean art

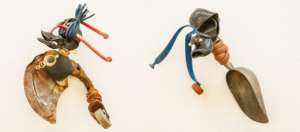

Tinotenda Chivinge, Zimbabwe Birds, 2023, all photographs by Tamirirashe Zizhou and courtesy of National Gallery of Zimbabwe

Trashy History: Tinotenda Chivinge’s Zimbabwe Birds

If there is one thing you will consistently find in exhibitions of contemporary Zimbabwean art, it is trash. Galleristically described as “found objects,” there is waste abound in the practices of some of the country’s most prominent artists like Wallen Mapondera, Victor Nyakauru, Terence Musekiwa, and Moffat Takadiwa who have all represented Zimbabwe at the Venice Biennale. Takadiwa, the poster child of upcycling, has systematized the recycling of rubbish into art objects. The artist has made a micro-economy of his practice, recruiting people in Mbare—a high-density and high-poverty Harare suburb—to collect specific items of refuse from a city overflowing with garbage. The artist favours computer keys and the leftovers of dental care: empty tubes of toothpaste and discarded toothbrushes made of colourful plastic.

Moffat Takadiwa artwork detail, from Vestiges of Colonialism, courtesy of National Gallery of Zimbabwe

While Takadiwa is remarkably precise in his recycling, constructing cohesive and distinct abstract works that teeter between the woven, the sculpted, and the painted; there is an unfortunate tendency for the abundance of “found material” in the contemporary scene to be overdone. In August 2023, walking through A Gathering – a group show of artist collectives curated by Fadzai Muchemwa and Zvikomborero Mandangu – at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in downtown Harare, it didn’t take long for me to get weary of all the creative reuse around me. Marcel Duchamp’s ghost (invoked ad nauseum in recent decades of Zimbabwean art history) was stirring in every corner. The ready was mingling with the made-and-discarded in a scrappy cacophony of resourceful repurposing and reuse and recycling and re re re re re…

QUACK! Something broke through the noise. It HONKED for my attention from a goofy splayed bill made from cracked and curved blue plastic. This was mounted to yet more plastic, bits and pieces of the material in its cheap and myriad forms – a flip-flop with dangling strap, a colourful knot of stretchy tubing – all coming together to form the figure of a bird complete with striped wings made of parts of what might be water sports equipment. The bird was one of fourteen (eleven mounted in a line on the white gallery wall and three more arranged on a plinth) all comprising some combination of trash. One had a battered film camera for a chest, a roller wheel for feet, and a rusty knife and fork holding its tetanus-threatening head together.

The sculptures were made by Tinotenda Chivinge and titled: Zimbabwe Birds.

I had to laugh.

The Zimbabwe Bird is a national icon in the truest sense of the term. It is the literal emblem of the nation, featured prominently on our flag and taking pride of place in the coat of arms. The bird is Chapungu or Hungwe (or the Bateleur Eagle and Fish Eagle in settler-speak). It is totemic, sacred, awesome, derived from the famous eight soapstone carvings of the bird that date back to the eleventh century and the medieval walled city of Great Zimbabwe, the House of Stone from which the nation takes its name. Like most objects “found” in Africa by Europeans, these birds were stolen in colonial conquest but since Zimbabwe’s Independence in 1980, seven have returned home. Only one remains abroad, enshrined at in Cecil John Rhodes’ bedroom at the Groote Schuur Estate in Cape Town. It’s quite a shit scenario, given the Rhodesia of it all, and one only partially remedied by Sethembile Msezane’s iconic performance as Chapungu in the place of Rhodes’ “fallen” 81-year-old monument.

Zimbabwe Bird sculpture in situ at Great Zimbabwe, February 20, 2020, photograph by Jekesai Njikizana (@izimphoto)

Speaking of Cecil John, the Rhodes National Gallery was founded in his name in the Southern Rhodesian capital Salisbury in 1957. Today known as the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in downtown Harare, the art museum is largely credited to the efforts of one Frank McEwen OBE, its premier director. McEwen was a settler who organized (per the standard art history) or invented (per Jonathan Zilberg’s more critical analyses) ‘Shona Stone Sculpture’ as a recognizable movement and inserted a ‘novel’ Black Zimbabwean artistry into the international circuit of modernism. One of McEwen’s central conceits was that the practice had no modern precedent, it was “lost in time,” a direct line from ancient times of “myth and magic” associated with (amongst other things) Great Zimbabwe and its soapstone birds.

Delegates at the International Conference on African Cultures, 1962, McEwen circled in yellow; photograph courtesy of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, edits author’s own

In 1961, during McEwen’s directorial tenure, the First International Conference on African Cultures (ICAC) was hosted at NGZ. This was a remarkable gathering of delegates from across the continent and the western world, discussing the global influence of African culture. This was restaged in 2017 under the theme of “Mapping the Future” and again in 2021 with restitution and repatriation shaping the agenda. The museum’s current director, Raphael Chikuwka, remarked at the time that “having your own heritage benefitting others is unfair and must be corrected,” a sentiment that looms heavy over that last soapstone bird which remains on display to anyone curious about how a master-coloniser lived.

With all this on my mind, I looked at Chivinge’s lineup of Zimbabwe Birds, assembled from old shoes and rusted metal, and I simply had to laugh.

This artwork says: Hey, it’s alright, don’t worry about that centuries-old soapstone bird with massive cultural, historical, and patriotic significance, I’ve got plenty of birds for you … except they’re made out rubbish because that’s all I can find these days and they only really look like birds if you imagine them to… This is no Chapungu, it’s more of a dhadha (duck).

Each of the birds is a unique sculpture but, serialized and lined up on the wall, they bear some shade of the mass-produced commodity, not least because of their composite materials. The blue plastic of that first quacking bill had a scratched-up and smiling Spongebob Squarepants on it. Chivinge’s birds are cheap and scrappy. They point accusatorily to the conditions of production for many artists in Zimbabwe, to a meagre arts economy that necessitates resourcefulness at an incredibly material level, a fact that is often romanticised as plucky, green, and odds-defying.

Installation view of Tinotenda Chivinge’s Zimbabwe Birds and Shiri dze Midzimu as seen in A Gathering, 2023

When the Rhodes National Gallery was established sixty-seven years ago, expert carving of stone with a “tribal consciousness” (McEwen’s words) was the pinnacle of artistry for Black makers, tracing all the way back to the soapstone eagles that guarded a great civilization. Today, the National Gallery of Zimbabwe displays birds made of trash and platforms artists who revel in the rubbish heap. This is by no means a decline in sculptural quality, and I don’t intend to deprecate the curatorial work happening at NGZ either. Rather, I applaud the criticalities that make art like this and put it on the walls of a state institution. Chivinge’s Zimbabwe Birds humorously mingle strands of national art history – restitution of heritage, indigenous modernism (or not), and economic crisis –to demonstrate the cultural and economic context of Zimbabwean sculpture right now. QUACK QUACK!