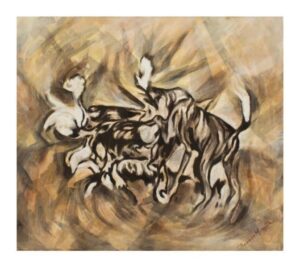

By looking at these species, you’re not just looking at a representation of an East African landscape but a metaphor for abstract emotions that Musoke hints at in her visceral vicissitudes of a pack of dogs violently tearing apart a prey.

Wambui Wa Mwangi on the work of the Ugandan artist Theresa Musoke, who lives in Kenya.

Dancing with the trees, 1990s, mixed media on canvas

Theresa Musoke

Time, perception, image

From vivid to muted sky blues and hints of green. Human life and plant life intertwine in Theresa Musoke’s Dancing with the Trees. In the mixed media piece, human beings become one with the plants. It’s as though their heads are sprouting with plants whose leaves whorl upward in the same synchronous movement as their hands. The plants crisscross and intertwine around their head and arms to become one. A camouflaging act? Deep blue streaks like narrow streams flow outwards from their torsos. These ‘streams’, as if leaving trails behind them, are surrounded by lighter shades of blue. There are some scant dabs of yellow across the canvas that seem to highlight movement in both life forms.

I come from a place (Limuru) where the vista is a perfect alchemy of evergreens and blue skies for a better part of the year. After viewing Dancing with the Trees, which, for some unknown lingering emotions at the time and a hardy fascination, a familiar chord was struck. The waves of plant life and human feet trudging along an invisible ground. It’s the interconnectedness of the presence of living things in environments across the world, in Eastern Africa. I have come across this exploration in the subsequent works by Theresa Musoke. Works for some covert reasons evoke memories, questions I have of the past, and deep-seated emotions of attachment to Limuru. This work made me seek her.

There’s an enduring factor in every piece that was exhibited in Musoke’s (b: 1944) latest exhibition—The Presence of Living Things: A Retrospective 1963-2025-which is her intentional choice not to focus on too many differing subjects as one often finds in most landscape art. Musoke focuses on only one enduring subject, which then sprawls into the canvas, evoking a largeness in being like no other. A pack of wild dogs, a herd of elephants, a forlorn woman, a boy gazing at you…

Wild dogs with a kill, 2005, mixed media on canvas

Her practice seems to align with what Hito Steyerl describes as “a horizon that quivers in a maze of collapsing lines,” because her orientation and conceptualization of East African landscapes give way to presence. Her work rejects an all-encompassing view of landscape but rather embraces the complexity and interconnectedness of the natural world and any landscape in general.

In the exhibition, which was showing her work for the last sixty years, Musoke’s surreal and semi-abstract landscapes zoom in on these subjects, which seem to have lingered in her memory.

Woman seated in blue, circa 1980s, mixed media on canvas

Theresa Musoke, who is Ugandan, lived in Kenya for most of her adult life, for over 20 years. The Kenyan wild landscape, therefore, somehow finds its way into her artworks. Her oeuvre spans paintings, lithographs, drawings, and sculptures. She describes most of her work as stemming from memory. Indeed, memories are unwholly and warped, stacks of copious images and polyphonous sounds in our minds. At least this is how I perceive memory, which then informs my perception of the future and aids in recalling my past. Memory is, therefore, a stimulus for recollection, a tool that enhances perception. Tim Ingold in The Temporality of the Landscape says it better:

“To perceive the landscape is, therefore, to carry out an act of remembrance, and remembering is not so much a matter of calling up an internal image, stored in the mind, as of engaging perceptually with an environment that is itself pregnant with the past.”

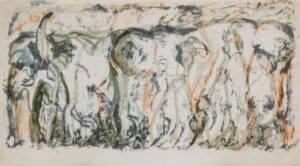

By looking at these species, you’re not just looking at a representation of an East African landscape but a metaphor for abstract emotions that Musoke hints at in her visceral vicissitudes of a pack of dogs violently tearing apart a prey or a herd of elephants in motion, foraging.

Elephants, circa 1960s, lithograph on paper

Nature can be a metaphor for anything and everything. In the African context, animals are not just animals but symbols of human vice or ingenuity, evil vs good. To Musoke, landscape painting is indeed complex, hence her resort to semi-abstract form. She says in an interview:

“The whole thought of painting is a strange one…,… most people want you to put it down in words, but the truth is if I could tell it, then I wouldn’t paint it. Therefore, to start explaining my paintings becomes ridiculous! It’s about nature and the many parts of it. I normally don’t tell a story as such. It is a very difficult thing to put your feelings into words. In my art, I precisely have the joy of doing just a beautiful thing.”

I found harmony in her surreal semi-abstract work; cohesion in the complex life forms in motion. There’s a generosity and openness to conviviality as Francis Nyamjoh views and espouses it— a shared becoming, an incompleteness, and interdependence.