Until December 6 other, less known work can be seen in the Betty Cunningham Gallery in New York.

First published: November 2014

About Traylor:

(article of Roberta Smith in the New York Times, July 4, 2013)

The Shape of the World Passing Before His Eyes

Bill Traylor’s talent surfaced suddenly in 1939 when he was 85 and had 10 years to live. By then he had left the plantation in southern Alabama where he had been born a slave in 1854, and, after Emancipation, scratched out a living as a sharecropper. He moved to Montgomery, the state capital, where he slept on a pallet in the back room of a funeral parlor and spent his days sitting on a wood box watching the world go by on Monroe Street, the center of the city’s lively black district.

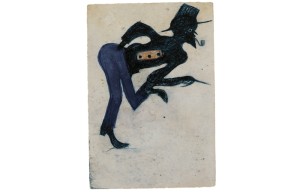

Untitled, 1939-1940

Untitled, 1939-1940

One day Traylor picked up a stub of pencil and a scrap of cardboard and began to draw. Over the next three or four years, alternating between memories of sharecropping and what he saw before him, he produced hundreds of drawings and paintings that rank among the greatest works of the 20th century. Traylor was a natural stylist and a born storyteller who pushed images of the life around him toward abstraction with no loss of vivacity. At once modern and archaic, his art offers proof of Jung’s collective unconscious but also of an indelible individual talent.

Traylor’s efforts exist because within days of making his first drawing, he acquired a devoted admirer: Charles Shannon (1914-96), a young white artist from Montgomery who began visiting him every week, bringing art supplies, buying some drawings and taking others for safekeeping, since it was apparent that they would otherwise not survive.

One is grateful to Charles Shannon’s keen eye and devotion when viewing the side-by-side shows of Traylor’s work at the American Folk Art Museum. “Bill Traylor: Drawings From the Collections of the High Museum of Art and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts,” a traveling exhibition making its final stop, includes nearly all of the Traylors owned by the two institutions of its title. (The 29 from the Montgomery museum were a gift from Shannon.) “Traylor in Motion: Wonders From New York Collections” in an excellent in-house effort organized by Stacy C. Hollander, the American Folk Art Museum’s chief curator, and Valérie Rousseau, its new curator of self-taught art and Art Brut, who have also overseen the guest exhibition’s stop here.

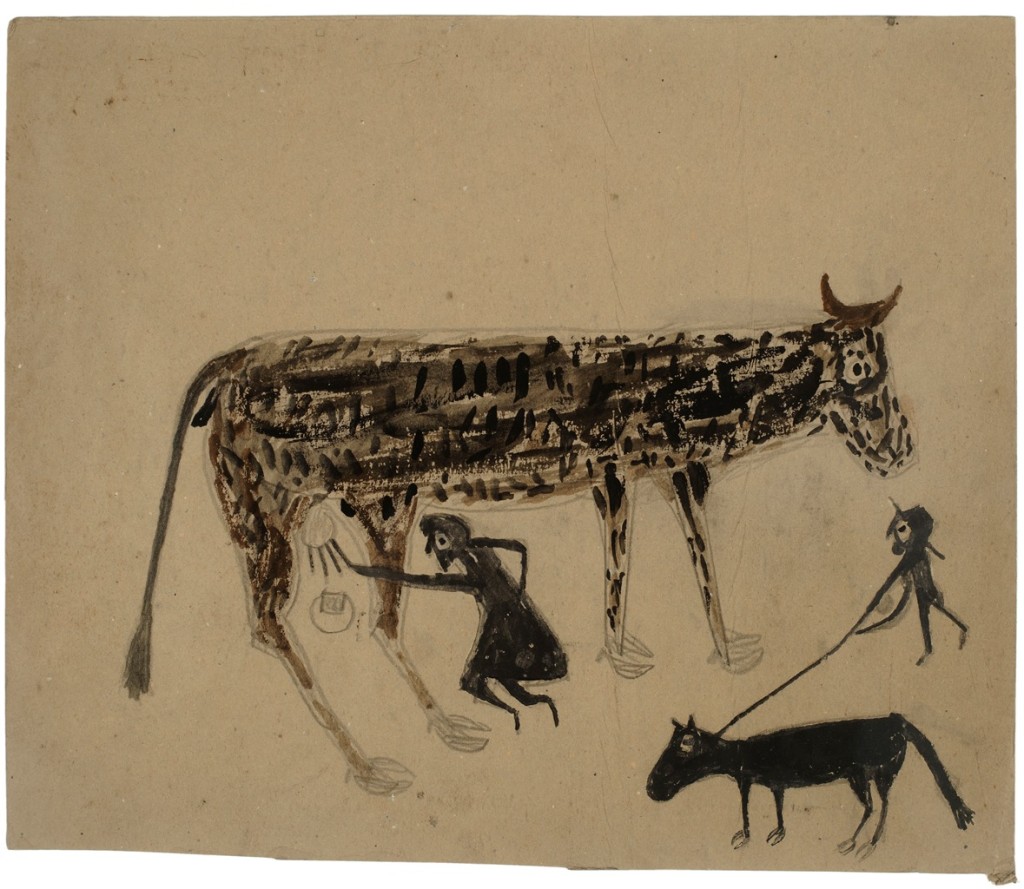

Untitled, 1938-1942.

Untitled, 1938-1942.

The first in-depth examination of Traylor’s achievement in a New York museum, these shows present a total of 104 drawings and paintings in combinations of graphite, pencil, colored pencil, crayon, ink, watercolor and poster paint, on salvaged cardboard and paper. They offer total immersion in his late-life burst of genius, albeit under crowded conditions that sometimes inhibit full appreciation.

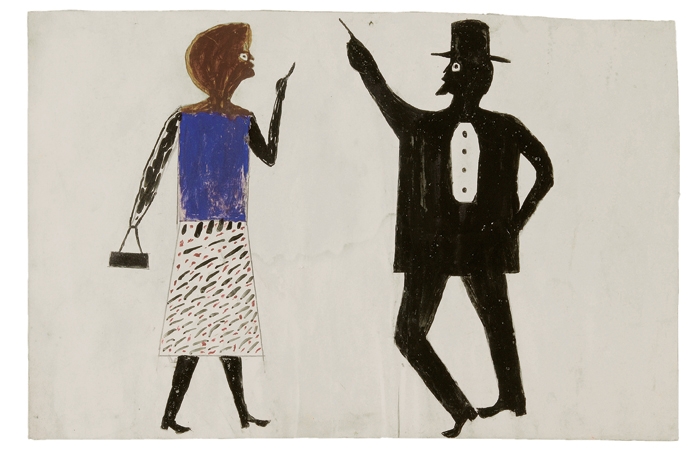

Traylor’s images depict mostly black people but also some whites, capturing a world that seems eternally fraught: the animals alert, the people wary. The mood is tightly wound, sometimes antic.

One possible source for his sharp-edged, implicitly geometric figures is weather vanes, although his silhouettes are considerably enlivened with distinctive textures, expressive button eyes, a sense of fluid movement and bright color. His characters include elders who sit in chairs or walk with canes, younger folk who dance, cavort on rooftops, raise barns, drink from flasks or argue. There are assorted dogs that snarl or just nose around, and lots of birds and livestock, especially bulls, horses, mules and pigs that are seen in profile, posing for markedly affectionate portraits. Sometimes Traylor’s figures perch, climb or even merge with abstract shapes that have come to be called constructions and can suggest blacksmiths’ anvils.

Untitled, 1938-1942.

Untitled, 1938-1942.

Especially in the scenes that Traylor called “exciting events,” we often glimpse the hardscrabble hurly-burly of life for sharecropping blacks during Reconstruction. Sometimes nature provides the excitement. Among the show’s most striking works is a pencil drawing that depicts, top to bottom, a man driving a plow, a fat rippling snake and an old woman with a cane and a small frantic child. At the bottom of the drawing, three dogs and two boys chase a rabbit. They seem to be in a separate narrative.

In other exciting events, figures swarm over (and under) boxy houses raised on blocks, often wielding flasks, hammers or axes. It is hard to know if they are building, partying or engaged in an internecine power struggle. The undercurrent of anxiety, of cheerful malice if not threat, seems to say something about the realities of Southern life before the civil rights movement.

Untitled, 1938-1942.

Untitled, 1938-1942.

This point is suggested by the first work you see here in the “Traylor in Motion” exhibition: a large drawing of a small white man walking a ferocious dog several times his size. It is comical, but also a suitable metaphor for white power and white cowardice in the Jim Crow era.

But there are other levels of reality in Traylor’s drawings, all of which reward close attention. One is the sense of gesture and personality conveyed by small details. For example, nearly every figure is equipped with an accessory, and sometimes a few: if not a cane or flask, then a hat, purse or cigarette. Sticks are plentiful, often wielded by smaller childlike figures who poke animals and grown-ups in the behind.

Then there are the physical realities of Traylor’s distinctive art objects themselves. Often his figures are fleshed out from geometric infrastructures — hard-edged rectangles or squares or more free-form designs, like the straight and curving lines of green pencil visible in the body of a charcoal-and-pencil horse that is unusual for having a rider. (Unfortunately, the drawing, from the High, is hard get close to; the infrastructure is most visible in the catalog.)

Traylor’s surfaces suggest an artist alive to every mark and line who placed his motifs with acute spatial wit. Especially in the more complicated scenes, this can make his unembellished backgrounds tilt and bend, as figures rush this way and that. His sensitive use of the irregularities of his salvaged cardboard, with its unpredictable shapes, stains and tears, often added drama.

Untitled, 1940-1942.

Untitled, 1940-1942.

This occurs in a dark black drawing of a man with a hat and cane who seems to be performing on top of an anvil-like construction guarded by a barking dog; the animal is made more distinct and aggressive by a tiny V of white that separates his ear from the black shape behind it. The man throws open his arms, cane in his right hand, perhaps taking a final bow. His gesture reaches across the oddly lobbed, slanting piece of cardboard — possibly from shirt packaging — on which the scene is drawn. We see him as if in a beam of light or through the crack of a stage curtain.

This show firmly places Traylor’s art where it belongs, in a tradition of abbreviated figuration that runs the length of human existence and across all cultures, from cave paintings, through Cycladic and African sculpture and American Indian ledger drawings, to Paul Klee’s high-strung creatures and George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. Part of this tradition’s greatness is that exists somewhat outside art history. You never know when it is going to be extended, or by whom.

Courtesy: Bill Traylor Estate.