“You allow me to glare into your eyes, with your hands steady on the table. You are calling for attention, not to your ego, but to your eyes, the window into your soul, as fractured as it is.”

Emmanuel Iduma speaks to Carrie Mae Weems.

Sentences for Carrie Mea Weems

The way things go, photographs can tell if you are present in the world. Never mind that it’s a world that tries to snuff out your existence, a life in which you have to be fearless, occasionally obscene. Never mind that the world is choreographed on a kitchen table, in the bedroom, and in spaces of private affection.

Your “Kitchen Table Series” is the version of an existence that leaves no nuance uncovered, as though the bedraggled objects of your ‘90s life are being washed without shame.

I will tell you a story, to illustrate the access I felt through your work. Months ago I was waiting for the train to arrive. You know how it is when you can see the other side of the subway, where the trains going in the other direction stop—I saw a woman arriving on the opposite platform, and one of her gloves dropped while she was walking. She wasn’t aware of this, and I felt a sudden urge to jump over the tracks to pick the gloves for her, regardless of the danger. My courage failed me; a train arrived for the woman and she entered. Yet, Ms. Weems, I looked at your photographs and I felt a surge of courage, as though I had outdistanced my fears of the world.

There is the sense that these are not photographs, but windows. You call me to peek into the painful joy of your staged persona. Here are photographs that speak—and I do not suggest “speaking” as a metaphor. The logic is twofold. First, the text panels embody voices that speak with uncompromising colloquialism. And second, these voices are impressed on the frame of the photographs; I am hearing them in every gesture.

You are a peculiar kind of witness. Socially involved art can be tiring, contrived, and sometimes ineffective. My frustration with such art is its over-reliance on visible prejudices, or evident mis-happenings—too much is being said. Once the present is sidestepped, once fundamental absences can be evoked in the work, once a subject’s gestures can say only enough, witnessing is complete.

I trust you with my impressions because you trust me with yours. In the original sense, the implication of the meaning of an impression could be said to operate as a force field; “impression” was used to signify the power of uniting mentally the ordinary understandings conveyed by the five physical senses. I did not think your photographs aimed to question our ordinary understandings of things, our basic assumptions about the fractures and devastations of love and of being female. I thought they wanted to show things as they were. Isn’t this a dangerous form of ethics, to evoke sentiments that leave things in place, only showing? No: the despicable ethics would be one that suggests a looking away.

You allow me to glare into your eyes, with your hands steady on the table. You are calling for attention, not to your ego, but to your eyes, the window into your soul, as fractured as it is.

By now, you know I am addressing a you that is I. The real power of the photograph is in the extent to which it allows for an unburdening. It’s like saying, “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.” I come to your photographs not to find you. In my mind it doesn’t matter whether or not these photographic narratives are autobiographical. The essential requirement for my impressions to become valid is that they unravel the indecorous nature of my own soul. The photographs in “Family Pictures and Stories” are skirting the edges of my past; I realize that my inscrutable impressions as a child have been brought into view. It is in this regard that I discover your photographs as a confessional, the booth where redemption is traded with shame.

From the outset, when you confront me I think of my mother and sisters. I know I am seeing the world as a man. With this comes with a baggage of patriarchy, a sense of senseless privilege existing immemorially. I recognize in myself a relationship with a privilege I did not demand, but which I enact by the simple fact of being a man. The sort of man in your photograph that sits at the head of the table, eating, as though he owns the entire food chain. Or where he’s not sitting at the head of the table, you watch him while he smokes. I grew up being taught it’s the woman’s responsibility to watch the face of the man, to decipher his unspoken gestures.

“Heaven,” you write, “lies at the feet of women.” That says it all, doesn’t it? In your long black dress, your feet are steady. With these feet you have roamed the world, conquering institutions as you go. No distance is too far and no landscape is too wide. If that isn’t heaven, what is it?

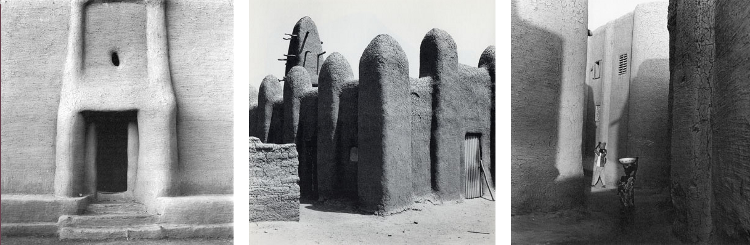

It’s the story of your work as a photographer, this outpacing of distances. Your vision could not be contained within your body, or within biographical narratives, so you went into the street, uncovering slave coasts and negotiating African identities. You had questioned patriarchy; it was time to question history. What’s fascinating is that by questioning you intended to disrupt—each time I return to photographs in “The Louisiana Project, 2003” I see a knife cutting through a painted object like Newman’s zip paintings, and I hear the blues music from Christine Meisner’s film “Disquieting Nature.”

I think of how, with “Africa, 1993”, you bring things to a calculated pause. A pause that is made possible through the architecture, like frozen music; music that seems to uncover the holes that lie hidden on the continent. This, I imagine, is how to phrase the past as a song, a cry from the river of Babylon, where the oppressed are said to sit, weeping. History, as your photographs remind me, brings the present to a pause. I don’t imagine it’s your task to tell me what to do during this pause—an umpire wouldn’t advise players on what to do during the break between both halves of the game.