Rashid Johnson is one of the artists in The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World, to be seen in The MoMA until April 5, 2015

About:

Johnson (1977, Chicago) first came to prominence in 2001 when he was included in Thelma Golden’s important exhibition, ‘Freestyle’, at the Studio Museum in Harlem, which showcased 28 young African-American artists interested in ‘redefining complex notions of blackness’. As a result, he is often summarily explained through the ‘post-black’ genealogy, as the younger sibling of an artist like Glenn Ligon (who, along with Golden, coined the term in the late 1990s). Yet with ‘Shelter’ – which continued the South London Gallery’s tradition of offering international artists their first solo exhibitions in the UK – Johnson was given the space in which the power, scholarship and humour of his work could play out.

The Long Dream, 2014.

The Long Dream, 2014.

(from BrooklynRail, February 24, 2014, Ange-Aimée Woods)

CPR: You grew up in Chicago in the 1970s in an afro-centric household. Your mother holds a doctorate in African History. How has your childhood influenced your work today?

Rashid Johnson: My childhood is a big influence in my work. As a kid, my parents were really interested in the afrocentric movement, and they embraced it: My mother wore daishikis, we celebrated Kwanzaa and so on. Then, at some point, this wasn’t interesting to them anymore in the same way, and they stopped. So my work definitely has some kind of nostalgia for that experience, when my life was full of African materials and a particular kind of African-American cultural understanding. Plus, we listened to a lot of jazz in my house, and my dad built CB radio systems, and both music (particularly record covers) and radio equipment appear in my work a lot.

Islands, 2014.

Islands, 2014.

CPR: Your work is considered a leading example of “Post-Black Art.” I understand there was a time when you reacted negatively to this label. How has your opinion of the label changed and why?

Rashid Johnson: I like to say that I’m not sure what “post-black” is, since I’m definitely still black. I think the phrase is often used to draw a distinction between black artists whose work is focused on the history of slavery and oppression of black people in America and those black artists whose work is about their own identity as black people but not so much focused on that same history, at least not in the same way. My work has lots of reference points for me: my history, art history, black history. Maybe that’s why people like to use the phrase “post-black.” The work isn’t focused on one thing.

Islands, 2014, installation view.

Islands, 2014, installation view.

CPR: You use many commonplace household items in your work such as soap, books and record covers. You call this process “hijacking the domestic.” What role do these items play in your work?

Rashid Johnson: They come from personal experience and all have meanings and history for me, but they don’t mean the same thing to everyone. It’s interesting to see how different people see the same objects and create their own narratives and assign their own meanings. For instance, many of the books in my work were books in my house growing up. I read many of them as a kid. And in my work I carry with me what those books mean as pieces of writing while also employing them as a mark-making technique.

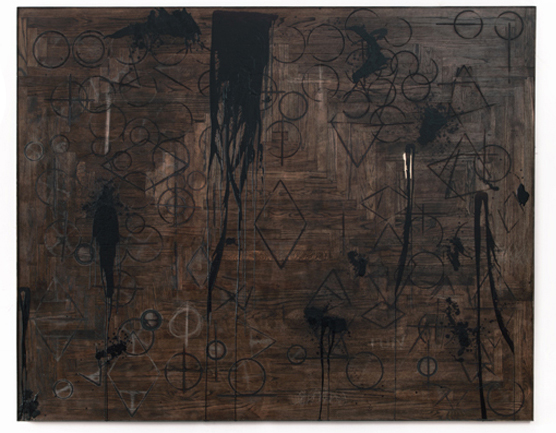

Omega, 2011.

Omega, 2011.

CPR: You refer to your paintings as “Cosmic Slop.” What is cosmic slop?

Rashid Johnson: The phrase “Cosmic Slop” comes from an album by Funkadelic that came out in 1973. It refers to a fictional dance, “Let’s do the Cosmic Slop,” and I like the idea that this dance has something to do with the performance of making a painting. When I make these works in the studio, I move around them on the floor, on the wall, back on the floor, and I realize the movement ends up becoming something like a dance that the painting comes out of.