In February 2024, The Metropolitan Museum of Art will present the groundbreaking exhibition The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism. Through some 160 works, it will explore the comprehensive and far-reaching ways in which Black artists portrayed everyday modern life in the new Black cities that took shape in the 1920s–40s in New York City’s Harlem and Chicago’s South Side and nationwide in the early decades of the Great Migration when millions of African Americans began to move away from the segregated rural South. The first survey of the subject in New York City since 1987, the exhibition will establish the Harlem Renaissance as the first African American–led movement of international modern art and will situate Black artists and their radically new portrayals of the modern Black subject as central to our understanding of international modern art and modern life.

Aaron Douglas is one of the artists in this exhibition.

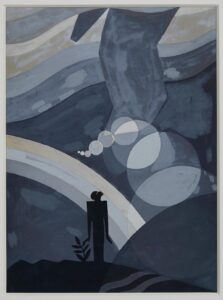

Aspiration, 1935, (collection National Gallery of Art

Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas, widely acknowledged as one of the most accomplished and influential visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance, was born in Topeka, Kansas, on May 26, 1899. He attended a segregated primary school, McKinley Elementary, and Topeka High School, which was integrated.[1] Following graduation, Douglas worked in a glass factory and later in a steel foundry to earn money for college. In 1918 he enrolled at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, and in 1922 earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts. The following year he accepted a teaching position at Lincoln High School in Kansas City, Missouri, where he served as instructor of art for two years. A serious reader from boyhood, Douglas kept abreast of the growing cultural movement in Harlem through the pages of two influential periodicals: The Crisis, published by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and edited by W. E. B. Du Bois, and Opportunity, the monthly publication of the National Urban League edited by Charles S. Johnson. Word of Douglas’s talent and ambition soon reached influential figures in Harlem, including Johnson, who was actively recruiting young African American writers, poets, and artists from across the country to come to New York. In 1924, Ethel Nance, Johnson’s secretary, wrote to Douglas encouraging him to come east. Initially Douglas declined, but the following spring, at the conclusion of the school year, he resigned his teaching position and traveled to New York.

The Creation, 1927

Douglas arrived in Harlem shortly after the publication of what was immediately recognized as a landmark publication: the March 1925 issue of Survey Graphic titled, “Harlem: Mecca for the New Negro.” This special issue included an introductory essay by Alain Locke, intellectual founder of the New Negro movement, with additional essays by other progressive African American leaders. When interviewed late in his career, Douglas declared that the Harlem issue of Survey Graphic was the single most important factor in his decision to move to New York.

Welcomed by the leaders of the New Negro initiative, Douglas enjoyed the support of both Johnson, who arranged for him to study with German émigré artist Fritz Winold Reiss (American, 1888 – 1953), and Du Bois, who gave him a job in the mailroom of The Crisis. Encouraged by Locke, Reiss, Du Bois, and others to study African art as a rich source of cultural identity, Douglas also absorbed the lessons of European modernism as he forged his own visual language. Soon illustrations by Douglas began to appear in Opportunity and The Crisis. In the fall of 1925, an expanded edition of the Harlem issue of Survey Graphic was published in book form. Titled The New Negro: An Interpretation, the anthology included illustrations by Reiss and his new student, Douglas.

In 1927 Du Bois invited Douglas to join the staff of The Crisis as their art critic. That same year James Weldon Johnson, poet and New Negro activist, asked the young artist to illustrate his forthcoming collection of poems, God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. Critically praised, God’s Trombones was Johnson’s masterwork and a breakthrough publication for Douglas. In his illustrations for this publication, and later in paintings and murals, Douglas drew upon his study of African art and his understanding of the intersection of cubism and art deco to create a style that soon became the visual signature of the Harlem Renaissance.

Judgment Day, 1939, (collection SCAD (Walter O. Evans))

Numerous commissions followed the publication of God’s Trombones, including an invitation from Fisk University in Nashville to create a mural cycle for the new campus library. In September 1931 Douglas sailed for Paris, where he undertook additional formal training and met expatriate artist Henry Ossawa Tanner (American, 1859 – 1937). Following a year abroad, Douglas returned to New York, where he continued to receive commissions and, in 1933, mounted his first solo exhibition at Caz Delbo Gallery. In 1936 Douglas completed a four panel mural for the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas. Only two panels from this set survive. One of these, Into Bondage, is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Art.

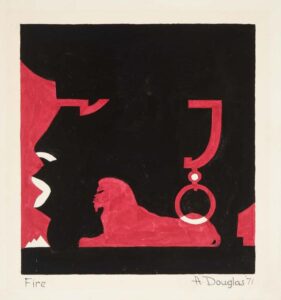

Cover of the magazine Fire!!, 1926 (courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery)

During the 1930s Douglas returned intermittently to Fisk where he served as assistant professor of art education; in 1940 he accepted a full-time position in the art department. Although teaching in Nashville, Douglas and his wife, Alta, retained their apartment in Harlem, where they remained active in Harlem’s cultural community—albeit now a community severely impacted by the Great Depression. In 1944 Douglas completed a master of arts degree at Teachers College, Columbia University. At Fisk he became chairman of the art department, where he mentored several generations of students before retiring in 1966. In 1970 Douglas returned to Topeka, his hometown, for the first retrospective exhibition of his work at the Mulvane Art Center. The following year he was honored with a second retrospective at Fisk. Douglas died in Nashville in 1979 at age 80.

[1] Biographical information from Stephanie Fox Knappe, “Chronology,” in Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist, ed. Susan Earle (New Haven, 2007).

Nancy Anderson (National Gallery of Art)

September 29, 2016