For a long time, abstract work of African American artists was not popular. The art world and the market were not interested. Figuration dominated. That has changed.

Rob Perrée gives an explanation

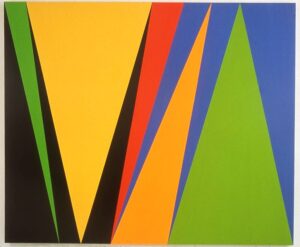

Odili Donald Odita, Flower, 2019, copyright the artst

Abstraction in African-American Art: A Long Journey

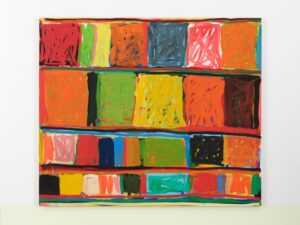

In 1995 I visited James Little’s studio in Brooklyn. It was one of the many African American artists I visited that year in preparation for an exhibition that I would present in 1998 in De Beyerd in the Dutch city of Breda: Postcards from Black America. It was a remarkable visit, because I saw work that I did not expect at all. Large abstract canvases, geometric areas of color, in harmony with each other or in an apparent clash with each other. Little read my surprise. “You see that I am closer to your Mondrian than to my black predecessors.” Twenty-five years later he would give a clear explanation for his abstract work in the New York Times: “Coming from my background, which was a very segregated upbringing in Tennessee, I felt that abstraction reflected the best expression of self-determination and free will. I have this affinity for color, design, structure and optimism.”

James Little, Portrait of a Star, 2001, Courtesy Kavi Gupta, Chicago

Of course I could or should have known that more black artists might choose abstraction over representation, but they were less visible for a number of reasons. That gradually became clear to me.

The 1990s saw a Black Renaissance, a new revival of black culture. Galleries began to become interested in the work of black artists. The financial crisis in American art in the late 1980s had brought many success stories to an abrupt bloody end. The Jeff Koons’ generation saw its market value drop drastically. Gallery owners had to look for other ‘material’. It was at this point that African American artists came into the picture. They were still cheap and, according to a number of gallery owners, their engagement seemed to be in line with a general need to be socially involved. In concrete terms, this meant that their art, conform to the stereotypical concept of wat black art was supposed to be, had to show itself black, and it had to deal with recognizably black themes. The prevailing thought was that the visitors and buyers also needed this.

That “had to” should be nuanced. From the 1920s onwards, most black artists made figurative work because they wanted to be recognizable and accessible to their own people and because they wanted to provide a general insight into their (often difficult) daily lives. In the 1960s and 1970s – when the Civil Rights Movement manifested itself – there was an additional political component: according to the Black Panthers and other activist groups, the work of an artist had to serve the fight for equal rights. Moreover, black Americans grew up in a tradition of storytelling. During slavery, they not only kept the memories of Africa alive with stories, they also strengthened their mutual bond and kept their cultural traditions alive with them. Figuration is the best way to make that visible.

So it was natural for most black artists to make it clear in their work that they were black, to strive for a black imagery, to deal with the themes that prevail in the black community. They already met the expected demand from the art institutions and the public.

Within such a context, it is not surprising that abstraction did not receive the attention it deserved. James Little’s complaint, made in 1995, that he struggled to gain a foothold in the art world was perfectly legitimate. The Black Renaissance passed him by.

Alma Thomas, Mars Dust, 1972, in collection Whitney Museum, copyright artist or artist’s estate via Whitney

The circumstances changed.

The art of black American artists is nowadays popular. That the urgency is now being felt has to do with a number of things. The generation that managed to enter the art world in the 1990s – Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall, Carrie Mae Weens, Glenn Ligon, Henry Taylor and others – has proved very successful. Not only has their artistic quality been recognized, they have also proved extremely successful commercially. They have paved the way for the current generation.

A lot has changed politically. Black Lives Matter has managed to capture the issue of blackness in three words and spread it all over the world, bolstered by social media that has made all the protests visible and, even if it sounds cynical, amplified by the visible, dramatic murder of George Floyd who has left virtually no one untouched. The art world has understood – it could hardly do otherwise – that you can no longer ignore the qualities of black artists. Even major galleries like Pace, Hauser & Wirth and David Zwirner now represent several African American artists.

The exhibition Soul of a Nation. Art in the Age of Black Power in 2017 at the Tate in London and later in a number of American museums has brought attention to the ‘forgotten’ black artists (between 1963 and 1983) in a fantastic way. The general public could take note of it.

The high demand for for the work of black artists has also ensured that the generation that preceded that of the 1990s – artists such as Feith Ringgold, Betye Saar, Howardena Pindell, the AfriCobra group and others – is suddenly offered retrospective exhibitions.

In the slipstream of these positive developments, there is also an eye for those black artists who work abstractly. It is not entirely true that none of them ever had a chance before – Alma Thomas had a solo at the Whitney Museum in 1972, Sam Gilliam represented the USA in the Venice Biennale that same year – but broadly speaking, the attention has been very limited so far.

Sam Gilliam, Carousel Light Depth, 1969, courtesy the artist

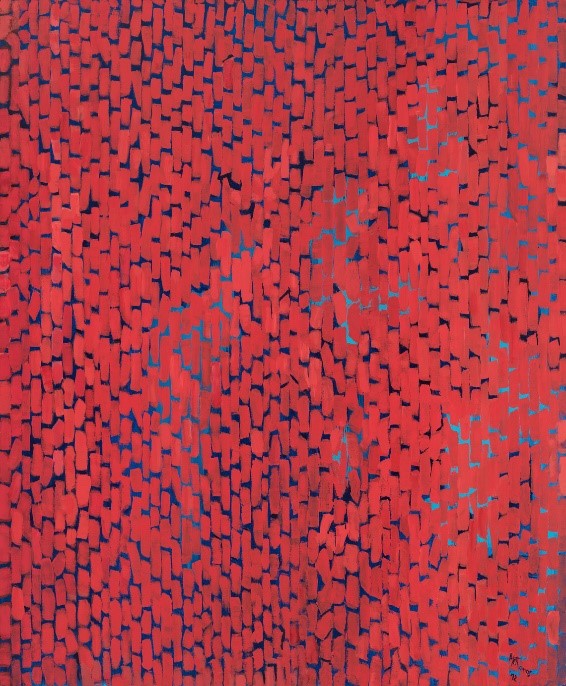

McArthur Binion, History: Of: Application, 1978, courtesy Lehmann Maupin

Some examples to illustrate the turnaround.

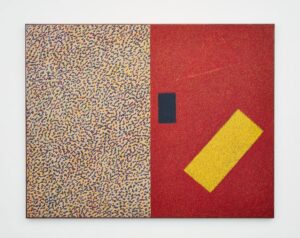

The colorful, abstract stain-painting draperies of Sam Gilliam (1933) are now not only included in many collections, but also often seen in exhibitions (Tate Modern, MoMA, Kunstmuseum Basel, Phillips Collection, etc.). The canvases of McArthur Binion (1946) – dense grids laid over personal documents – are now distributed around the world by Lehmann Maupin gallery. Jack Whitten’s (1939-2018) Black Monoliths honoring heroes like Ralph Ellison and Jacob Lawrence now fetch more than $1 million at auction. The stacked compositions of numerous saturated color fields, delineated by between three to five horizontal bands on square-formatted canvasses by Stanley Whitney (1946) have been shown not only in American museums, but also at the Venice Biennale and the Documenta in Kassel.

Jack Whitten, Black Monolith IV, for Jacob Lawrence, 2001, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Stanley Whitney, Untitled, 1998, copyright the artist, courtesy Lisson Gallery

The work of Mark Bradford (1961) is somewhere between abstraction and representation: on the surface it is abstract, what lies beneath it represents reality. He describes it as: “Think about all the white noise out there in the streets: all the beepers and blaring culture—cell phones, amps, chromed-out wheels, and synthesizers. I pick up a lot of that energy in my work, from the posters, which act as memory of things pasted and things past. You can peel away the layers of papers and it’s like reading the streets through signs.”

McArthur Binion has left his mark.

Mark Bradford, Los Angeles, 2019, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

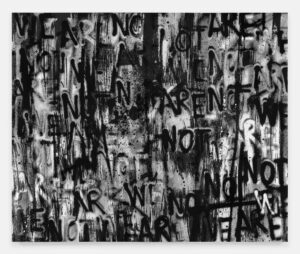

The dark works of Torkwase Dyson (1973) are unadulterated abstract. Her works play with the experience of space. She describes them as “my abstract works are visual and material systems used to construct fusions of surface tension, movement, scale, real and finite space.” The whimsical, abstract works of Adam Pendleton (1984) often contain text that responds to social events.

Torkwase Dyson, Extraction, Takes Courage for a Body to Get Down There, 2020, courtesy Rhona Hoffman / Adam Pendleton, Untitled (We are not), 2021, courtesy the artist

This is just a small selection of the black artists who work in an abstract way and who nevertheless, some very late, have been included in the success story of African American art in the US. The artist Rashid Johnson aptly puts it: “There is no battle between abstraction and representation. These are not adversarial positions. It’s like suggesting that John Coltrane has less of a voice than Stevie Wonder.”

The long journey has come to an end.