Spiritual practices, linked to masquerade inspire much of my approach to making and thinking through my research. I think my work is very much a mash up, a mash with masquerade and afro-futurism.

Raquel Villar Pérez in conversation with Alberta Whittle

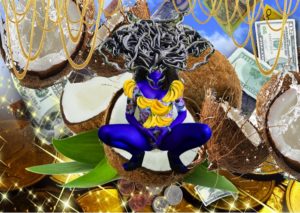

Celestial Meditations II, 2017

BUSINESS AS USUAL

An interview with Alberta Whittle

‘Business as usual’ is a set phrase used commonly in the business realm to manifest an ‘on going and unchanging state of affairs despite difficulties or disturbances’. It also serves to title Alberta Whittle’s first solo show at Tyburn Gallery, London. The artist adding a good deal of sarcasm on to it, humorously appropriates and reinterprets the tranquilising sentence to refer to the lethargic and stagnant nature of the art institutions governed by good intentions and mainly lack of commitment towards creating real spaces for diversity and inclusion within the arts.

I meet Alberta at Tyburn Gallery where we speak about the business of colonialism and its legacies today.

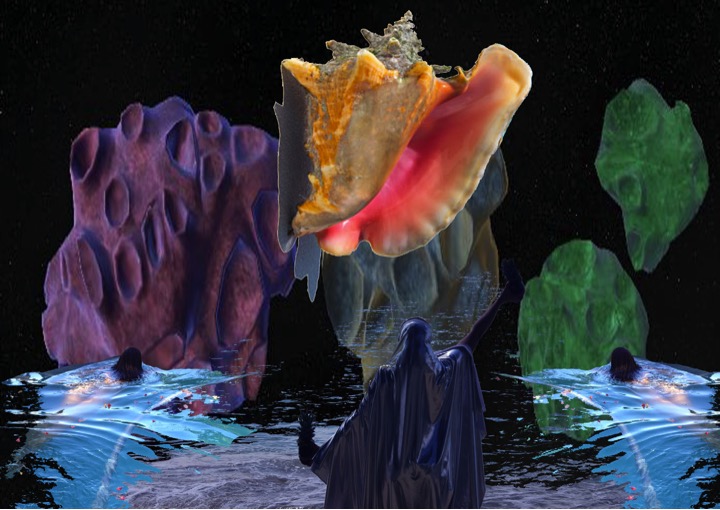

Celestial Meditations, 2018. Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

Raquel Villar-Pérez – Business as Usual has been your very first solo show in London hosted at Tyburn Gallery. Can you tell me more about how the exhibition came about and the choice of the title?

Alberta Whittle – I was approached by Alessandra to bring her some work for her to look at and then she invited me for a solo show to open at the end of May.

I usually tend to use humor in my work, and the title is meant to be tongue in cheek and reference the major themes in my work, which consider contested histories, climate colonialism, trauma and healing but also position widespread ambivalence to these topics. Ambivalence as a response interests me because it reflects such disinterest and discomfort with how privilege is enacted and engaged with.

In particular, there seems to be an expectation that we’ve moved past these histories of colonialism, imperialism or even recent histories of genocide, or that we need to move past them because it makes people feel uncomfortable.

There may be moments dedicated to speaking about these “difficult” histories or creating gestures to consider a parity of representation within institutions and museums, but it does feel facile, it can feel like a performance of sorts. Whereas what I’m hoping for is that we collectively actually become more involved in building institutional change through parrhesia [free speech], open discussions dedicated to reparatory justice, whatever that looks like for individuals or different communities.

The title Business as Usual, refers to this idea of what is happening every day, where there is no any real change happening

C.R.E.A.M, 2017. Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

RVP – There are a number of symbols that recur in your work. Particularly, in the works displayed at Tyburn Gallery, there is a prominent presence of the seashore, seashells and pineapples. These could be considered as part of the repertoire of the imaginary of that considered as the exotic. Can you expand on the use and meaning of these in your work and how it is also informed by science fiction?

AW – I generally feel quite perplexed when people consider the images in my works as exotic because for me they are not exotic; it’s more about one’s perspective! I think the images are much more haunted, for me, in particular when you see the water. I consistently create images in the intertidal zone, where the water signifies moments of arrival or moments of departure, a conflicting zone.

Most of these waterways were photographed at very specific places. This image has been taken in St James in Barbados, which is where the British first arrived in Barbados.

Meditation on Welcome, 2018. Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

These other collages show specific places in South Africa. A few years ago, I journeyed from Johannesburg to Cape Town, and often felt haunted by the water and the histories of loss it signified. This one in particular was inspired by a view leading down to Sea point, which I always saw as filled with Dutch ships from the colonial era.

But I am also looking at the potential healing qualities of water, where the sea exists as a place of healing, but also of loss, because the sea is also a graveyard, it has been for centuries; it existed as an active graveyard during the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and it is a zone that is still a graveyard now, if we consider the horrors of the refugee crisis with so many bodies being lost in the Mediterranean. So when I juxtapose images of the water with these collaged layers I am trying to encourage the audience to explore how we relate to these repetitions of loss. It feels as if we are still not dealing with history, because we are constantly repeating them. These crises are echoes of loss.

The seashells become symbols of sexuality, almost vulvic. And these vulvic images of shells contrast with other more phallic imagery, such as the pineapple. Within these tropes are questions around the performances of gender found in the Caribbean where the hyper masculine competes with hypersexualised and feminised images in dancehall culture.

Furthermore, the pineapple comes from this image I saw of Columbus arriving in the West Indies, where the painter would depict Columbus being greeted with “natives” holding up pineapples as a symbol of welcome. The pineapple then was mythologised as a symbol of welcome, which for me is a very convenient myth. So this idea that indigenous people in the Caribbean or the African Diaspora were welcoming Europeans within the settler invasion is a very troublesome myth. Much of my work deals with myths and attempts to create a puncture within those myths to reveal the varied layers related to power behind the construction of myths.

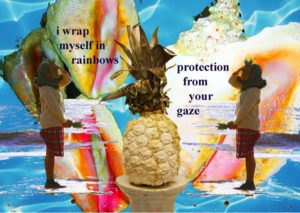

In many of my collages the image of me holding pineapples repeat and although there has been a reading that I am inspired by the Statue of Liberty, what I’m actually doing is semaphoreto spell out the word ‘welcome’. But rather than face the water and offer welcome to the settlers or colonialists as it has been depicted in 18th and 19th century prints, I face the viewer to spell out the words ‘welcome’, so that the message of ‘welcome’ becomes garbled or confused becoming ‘unwelcome’ rather than ‘welcome’ because they would be reading it from behind, and it wouldn’t make any sense.

(UN) welcome, 2018. Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

The silver figure is actually this phantom, this idea of being haunted by histories but also where black life can almost feel like embodying a haunting in the afterlife of slavery where there is still so much discomfort around working towards decolonial actions such as institutional change though reparations, cultural equity and parity.

I often feel very conflicted by Frank Wilderson III’s research on Afro-pessimism, whilst I find it some days incredibly sustaining and does bring a lot of my theories to life, I struggle with sitting in that pessimism, I do struggle with sitting at it and I am trying to be optimistic for a different way of being which is way for me the idea of collage becomes a way of shape shifting, and it becomes a way of manoeuvring.

Kamau Brathwaite’s research has been deeply inspiring within all of my research, especially his work on Tidalectics, which invites us to approach our understandings of the world with an oceanic worldview. Connected to his theories on sound and ‘riddems’ as methods to approach the contours of history is the limbo, constructed aboard slave ships and in plantation yards. My friend Camara Taylor also uses the image of the limbo as a dance form and as a visualisation of survival techniques for black people within their work. Similarly, in my recent film commission, Between a Whisper and a Cry, echoes of the limbo are present amidst imagery of hauntings as embodiments of black life.

And the limbo becomes a visualisation of ways in which, we, as people of color, we black people have to manoeuvre in order to survive in the face of white supremacy – we have to literally had to bend our backs to survive, so the silver figure which repeats across my practice presents the optic of history resurrected from the depths of the ocean. It is this phantom of ourselves that we are being haunted by.

A few years ago I was in a residency at Hospitalfield, in Arbroath, Scotland, and I became exhausted by being so easily identified as the Other, as a black person within this very small town. Growing up mixed race amongst my black family in the Caribbean, I never felt comfortable claiming Scottish identity, which felt alien to me. Yet, recently I realised that Scottish ancestry is evident on both my black Caribbean mother’s side of the family as well as on my white father’s side of the family. So I decided to confront this history by using masquerade in the collage work, wrapping myself in rainbows. By in dressing myself in traditional Scottish clothing, such as kilts or Arran jumpers becomes a form of masquerade where I’m assembling these tropes together but directly interrogate Scotland’s role within the slave trade but in a very personal way. Within this collage the vulvic shapes of the conches alongside the pineapple, which becomes a phallus as a means to speak about mythologies of welcome between settlers and indigenous people, as well as rapes by overseers and plantation owners throughout colonialism.

Wrapping myself in rainbows, 2018. Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

RVP – Would you frame your work as afro-futuristic, understanding as Afro-futurism in the way Mark Dery [Black to the Future] laid it out: ‘Speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of twentieth-century techno culture—and, more generally, African American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prophetically enhanced future’?

AW – Most of my research is related to Afro-futurism, but much more connected directly with a Caribbean Masquerade tradition. As a Caribbean person living between borders, Afro-futurism and how it relates to British or Caribbean identity feels different from the North American sensibility defined by Dery’s Afro-futurism. Working from a Barbadian perspective, methods of Masquerade in carnival as a means of assembling objects and images together definitely informed my aesthetic as well as my processes of making. Carnival always presented a kind of conflict between being extremely attracted to it but also actually quite frightened of the noise, and the pressure to perform, so it is really odd now that I now do performances.

The possibility for moments of transgression in masquerade, especially related to speculative queer futures is a significant thread within my practice. Drag and performance permeates Mas or Carnival and definitely dancehall culture, which has informed how I prepare my collages, especially earlier ones in my Big Red aka series where I use drag as a means to confront the expectations of gender within the Caribbean. These early works also became moments for me to develop my performance practice in a more dynamic way.

I think Afro-futurism and how it addresses forms of queer speculation really appeals to me, because of the way it makes us understand new technologies of the body, explore knowledge transference, and maybe similarly to Kamau Brathwaite, explore sound and ‘riddems’ as a method for expanding spatiality between the present, past and futures. The way I think masquerade connects with sci-fiction is by expanding on notions of shape-shifting, where traversing to another realm, or exploring the possibility of embodying another materiality as a means of flourishing or surviving or achieving a new spirituality is very sustaining within my practice.

Spiritual practices, linked to masquerade inspire much of my approach to making and thinking through my research. I think my work is very much a mash up, a mash with masquerade and afro-futurism.

Business as Usual, 2018. Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

RVP – I am really interested in the dialogue established between two of your works: (UN)welcome, that references the Statue of Liberty, and Meditations on Welcome, which I presume alludes to those who get to enjoy the paradisiac landscapes of the Caribbean, and who tend not to be the locals. I believe the dialogue is not only established between the two works, also placed next to each other in the gallery wall, but also enters in to the discussion of the present migration crisis, as the media puts it, not to mention Brexit. Tell me more about these works.

AW – The idea of welcome or hospitality is a very emotional concept for me. I have begun identifying more and more as being a first generation British Caribbean person with my right to be here; however, especially with the Windrush situation and Brexit my position feels especially precarious. In relation to ideas of welcome and the hostility, which I have experienced being here, claiming space is a driving force within my research for my practice, and above all questions of power and what conditions are in place with welcome and whom is welcome offered to.

If we consider borders, and the desire for borders, which is embedded within capitalism and white supremacy, how is that going to change with the current climate crisis? In my most recent work, Between a Whisper and a Cry, which looks at forms of decolonialisation and the climate related devastation that is accelerating in the Global South with the hurricane seasons getting so much longer, flooding, cyclones and earthquakes becoming more drastic, and even in the UK heat waves happening in February. So linking this extreme havoc of climate change with colonialism and borders feels very pressing in my work, making me wonder how relationships with borders may become even more tense, because essentially the Global South is already dealing with climate change because they are the vanguard, experiencing catastrophe before the West; so how do we understand welcome and who gets to offer welcome when climate change related catastrophe will manifest as land disappearing and communities and countries literally fleeing. That is very emotional for me.

Celestial Mediations II, 2017. Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

RVP – Can you talk about the use of collage as a strategy to represent multiplicity, plurality and ever changing narratives?

AW – Collage has become a very important facet within my work because it allows for fractures to happen within the gaze. In some ways this is about the fracture creating a break in the reading of my body, but it also is a way of building a different sense of myself, building a different body.

When I layer images together, they are often sourced from my archives, images from my journeying, image from sculptures I have made and images from performances. Connecting these images allows me to construct different mythologies, and explore how shape-shifting, as a methodology, encourages a speculative sense of futurity where new visual languages can be birthed. This idea takes us back to afro-futurism and AfricCaribbean masquerade.

I understand my body as constantly changing especially because it is a mixed body and I am very aware of how the body can change depending on geography, and depending of the gaze of the person who is reading my body. So collage allows me to play with my interiority, create modes of refusal against the racialized reading of my body as a multiple, mutating vision of self-defining personhood. In my work you will see instances of my body being a lot of mirrored in the images, – I’m two headed, I’m twinned, etc. Twinning can become a symbol of looking backwards but also looking forwards at the same time, like Janus.

Maybe collage can take us back to Kamau Brathwaite and his idea of tidalectics and the idea of limbo and the black body having to manoeuvre and shape-shift to survive, so the only way in which I feel I can really do that is by actually making sure that my body is actively shape-shifts and it is manipulated and manoeuvred in various different ways.

Celestial Meditations I, 2017. Courtesy Tyburn Gallery.

RVP – You are not only an artist but also a curator, and educator; in my opinion your work is illustrative of non-told stories/histories and possible futures. What are your views on how art may be of help to the current state of affairs?

AW – I’m very lucky that I’ve been part of the Transmission Gallery committee since 2015. I’m leaving now but this collective working with more than 11 individuals who sat with me on the committee has impacted my thinking in more ways than I can count. The work of the committee which is rooted in working towards decolonisation has led to some positive impact. There have been changes in the sector, where institutions are looking much more responsively towards how they understand representation and hopefully redefining their constituents. But intention is not enough, there has to be commitment to change, and I’ve seen that commitment coming from different pockets across the sector, which is a source of optimism.

As part of the work we are doing at Transmission, we have been challenging who our constituents are and have been working to open the gallery to communities who wouldn’t necessarily want to participate in contemporary art. This is a long-term commitment and the work is just beginning, but we are hoping to create some new strategies where, rather than existing as a conventional gallery space, we are straddling relationships akin to community building. Hopefully these changes can make people feel much more embedded and connected.

Within some of my other curatorial projects and social practice research I hope to open up conversations, so there is a sense of ownership around institutions, where these rarefied environments aren’t just for a privileged few but hopefully can become much more accessible and open to interrogation.

I’ve been lucky to be part of change but also witness change, but most of this is down to the energy and drive of the individuals I’ve worked with, who are highly committed to facilitating institutional change. And I think it is important for the sector to see that commitment in our programming and the work we are doing. However changes have to happen on a higher level, they have to change on a managerial level, and recognition of real change, is when you see people making decisions who are PoC [People of Color].

Talking to Alberta Whittle was an exercise of enlightenment, vulnerability and open-heartedness; our conversation let me reconsidering my positionality in the world, my privileges. It shook me out of my comfort zone and my preconceived ideas and opened a myriad of possibilities to interpret the world I live. Diligently researched, immensely wise and witty, Business As Usual is food for thought in a beautifully crafted collage form.

BIOS