“We use Afrosurrealism as a visual framework, drawing on mythology and symbolism, as well as our personal experiences as artists, to present new ways to imagine spiritual identity.”

Hamed Maiye and Adama Jalloh about their show An Ode to Afrosurrealism

An Ode to Afrosurrealism

The Horniman Museum and Gardens in South London hosts An Ode to Afrosurrealism. The photographic exhibition presents surrealism, spiritualism and our relationship with reality through a Black British lens. Rather symbolic itself the exhibition opened on the same day as the Horniman’s celebration of Black History Month and the 60th anniversary of Nigerian Independence.

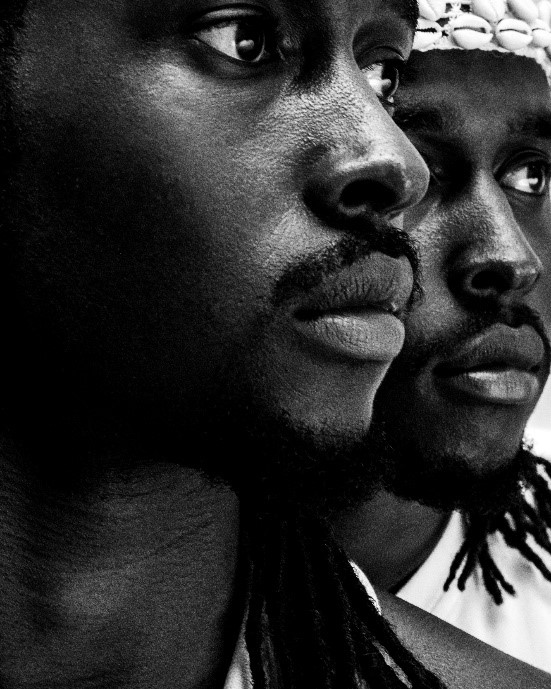

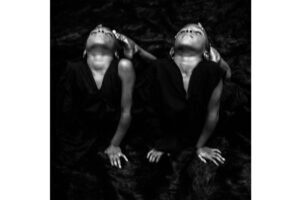

London-based photographers Hamed Maiye and Adama Jalloh made their collaborative debut to bring together a series of 25 photos for the show. Thematically An Ode to Afrosurrealism focuses on the number two as shown by twin imagery representing duality; union and division, reality and surrealism.

Maiye explains that “in this photo series we pay homage to Afrosurrealism, a visual and literary movement which considers what lies beyond the visible and material world, exploring the reality of the present and creating art that expresses the ‘otherworldly’. We use Afrosurrealism as a visual framework, drawing on mythology and symbolism, as well as our personal experiences as artists, to present new ways to imagine spiritual identity.”

Hamed Maiye & Adama Jalloh

Historically speaking Western religions have dominated over the Spiritualist practices of African and Caribbean communities. This is a legacy that derives from the missionary visits of white explorers, nuns and priests into Africa. Demonised as witchcraft, practices like voodoo and native magic have been portrayed as evil or satanic. Yet these are another form of indigenous culture that has been suppressed from the mainstream and replaced by a “sanitised” and approved form of Christian worship. Yet in recent years this form of Spiritualism has been growing in popularity around the world. Could this be a reclamation of the old ways that were previously “white washed” out of society?

Jalloh adds that “with a history of our stories being told for us and that still being an underlying issue now, Afrosurrealism feels like another way to combat that but also giving freedom in a broader way on how we choose to display our narratives.”

The self-directed narratives being told by Black artists pervades An Ode to Afrosurrealism. This is the direction that is emerging from the Black art world. Here the narrative of Black contemporary artwork in an establishment such as the Horniman Museum is important. Add to this the old lore and mythology it is presenting and audiences have a layered experience of old and new, traditional and fresh.

Both Maiye and Jalloh’s interest in culture creates a visual conversation between anthropology and mythology. Reminiscent to Joseph Campbell’s work on myth, the portraits almost parallel The Hero With a Thousand Faces. The premise of this book by Campbell focuses on the journey that an archetypal hero embarks on. This motif of “the hero’s journey” resonates with the Black British lens that Maiye and Jalloh cast here. Reclamation of the narrative is part of the journey to reclaim a sort of Black hero’s journey and bring life back into Black folklore.

In his book Campbell explains that “a hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man”. Here we echo the theme of duality found within An Ode to Afrosurrealism. There is the seen world contrast against the unseen world. There are the heard (white) voices of the mainstream contrast against the unheard (black) voices on the margins. There are the literal photographs we view contrast against the symbolism they represent.

The challenge of the journey here is to travel from our common world of inequality and discrimination, go into the otherworld and pass-through duality in order to understand both sides fully. Finally, we can bring harmony back from our journey in order to spread it into the wider world.

Hamed Maiye & Adama Jalloh

This is where I believe the motif of twins comes into power. Being genetically the same yet separate entities becomes a powerful reminder that we as people can be so different yet entwined from a common source. This is how we can celebrate, respect and see difference without feeling alien from one another. This is the union and division dichotomy that the artists intended.

In an interview with the Horniman Museum the artists added that “The use of twins started off as a way to explore how reality and surrealism reflect and inform each other, it also works to blur the concepts of absolute light or absolute darkness. It helps us to explore the nuances and spaces between the two. It also explores the dualities of self, and the spaces we inhabit internally.”

This is similar to the explanation of the Yin & Yang symbol. Each side is in flux and contains the other within it. Within us, we hold space for Otherness and the ability to host that which is not us. In other words, we have the potential for great compassion for things and people who are different. What happens if for a moment to relinquish our own ego identity and allow ourselves to see things from another perspective? We do not lose ourselves further but simply gain more insight to add to our being. Like the number 2 we move towards a state of balance and completeness. Our whole is greater than the sum of its parts. This is real magic.

Maiye and Jalloh also wished that An Ode to Afrosurrealism would inspire young artists to think laterally and consider new ways of making art by looking beyond the normal canon of spiritual iconography. “Afrosurrealism looks to challenge traditional western views and terminology in art-making. It allows the artist to assume the role of an anthropologist and choose the way they would like to story tell and document. Allowing artists to play this role enriches the museum context and creates more rounded experiences for the viewers.”

Hamed Maiye & Adama Jalloh

The Afrosurrealist movement is also gaining traction. From psychedelic music to Black filmmakers like Arthur Jafa adding a hallucinatory element to their videos, Afrosurrealism has re-entered the imaginations of the community.

The revival of the genre could be rooted in its fantastical escapism used to counteract oppression felt in the mainstream. It may be a satirical expression against violence and inequality highlighted across the world. Nevertheless, Afrosurrealism is always an introspective genre because its symbolism asks the viewer to understand things deeper than the surface. It is about imagination and bending the rules of reality to sometimes show just how absurd reality really is.

Perhaps with this new age of Afrosurrealism dawning, the genre is forcing us all to slow down at a time when the world is rushing back to normality. It is inviting us to look at how normal normality really was. It is reminding us that we can shape our world however we choose to. It is letting us know there are other choices out there for us. Sometimes it takes the irrational and strange to remind us of the magic and beauty waiting for us once we revolutionise human experience.