Ananias Léki Dago

Until September 25 in ‘Creative Africa’, Philadelphia Museum of Art

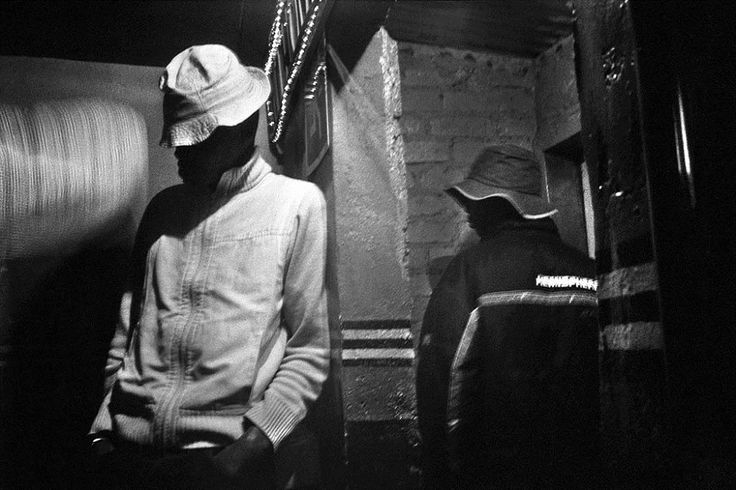

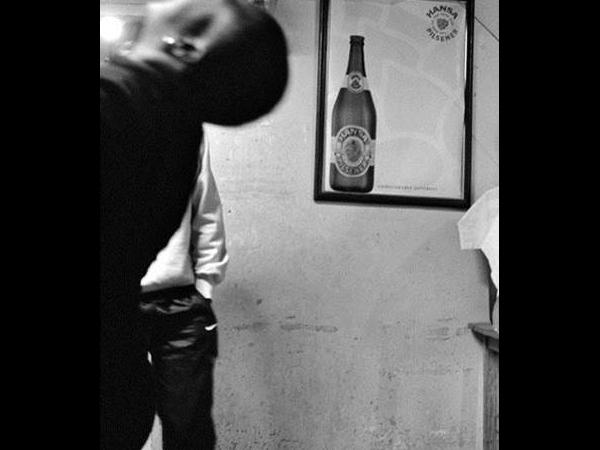

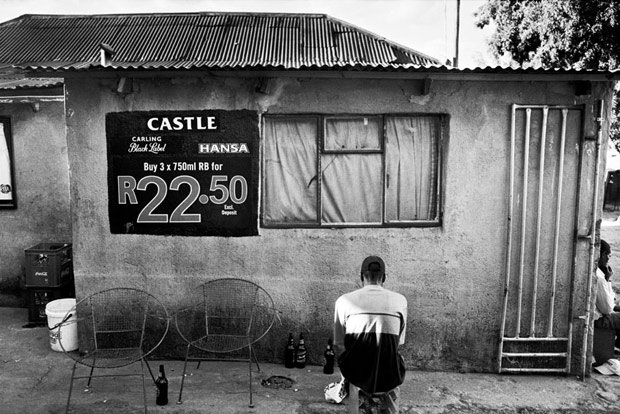

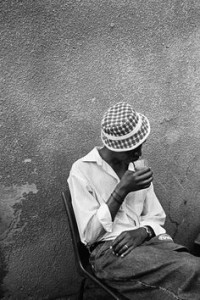

Shebeen Blues Series, 2006.

About:

Ivorian photographer Ananias Léki Dago was born in 1970. After a ten-year absence from his country following the Ivoirian crisis which forced him into exile in France, but which at the same time gave him the opportunity to experiment and travel at length in other African countries, he has finally returned to the Ivory Coast with a whole host of personal and collective projects. He has finally returned to the Ivory Coast with a whole host of personal and collective projects.

I went to South Africa the first time in 2006, armed with my Leica. One day, Andrew Tshabangu, a South African photographer, took me round Soweto. Soweto is huge and after a while we were thirsty. So Andrew said to me: “I’m going to take you to a shebeen.” Until then, I had no idea what a shebeen was. We went in, it was in the backyard of a house, there were people sitting there and it struck me that the decrepit old walls were full of stories. Some people’s faces – people up to the eyeballs in alcohol – were incredibly marked. There was something beautiful about their features. I found the place very photogenic too. But in addition to what interested me visually, I was interested in the very heart of the question, “What, in actual fact, is a shebeen?” In the course of various discussions, I discovered that shebeens – a kind of chop bar – are places that the township dwellers invented because the black populations were not allowed to drink alcohol. As all humans need to let their hair down, they created these informal, underground places to get together and reflect on their condition. “Shebeen” is an Irish word for an illegal alcohol outlet. The alcohol was made at the time by the women, who were known as Shebeen Queens. People gathered together in the shebeens both to drink and relax behind the authorities’ back, but also to discuss their concerns, questions relating to their culture, society or politics. Indeed political figures and activists such as Nelson Mandela and Miriam Makeba, but also writers and journalists, developed their thinking in the shebeens. They came there to redefine their cultural identity in terms of social and political issues. So the shebeens were a kind of recipient of the energy that led to the overthrow of the repressive apartheid regime. However, the flip-side of the coin is that a lot of people, who were completely frustrated, became dependent on alcohol. The shebeens thus destroyed a lot of black families in the townships.

I personally was interested in the post-apartheid shebeens, in seeing what had become of these historical places today. Today they are no longer illegal; everyone is allowed to drink alcohol. So, what would my appreciation be, as someone who is not part of this history? I called the book published in 2010 out of this long project “Shebeen Blues.” These photos convey what I felt when meeting the people who frequent them. The shebeens can be very noisy, but a feeling of solitude permeates my gaze. This was no doubt the state I was in when I went to discover these places. quotes from Leica Camera Blog, January 2014)