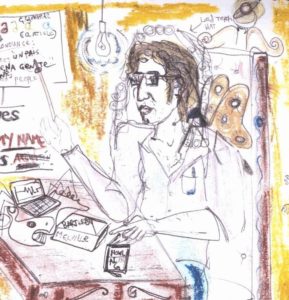

“The day I began to live and behave in a more nomadic way, I kept notebooks that departed from my more usual forms of creative activity. These notebooks filled with bestiaries, drawings that combined human and animal figures, with symbols from the religions I have encountered, and notes from songs: an interplay of my experiences, suffering, pleasures, memories, poems, stories and forces surrounding me as I went about travelling like a wayfarer, a Homo Viator. Restless travelling does not change how the artist’s primary concern lies with inner experience… Geography looks absurd in relation to art.”

Arturo Desimone (1984, Oranjestad, Aruba), artist, writer, poet, about his work

Arturo Desimone

A selection

A.

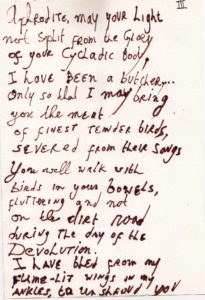

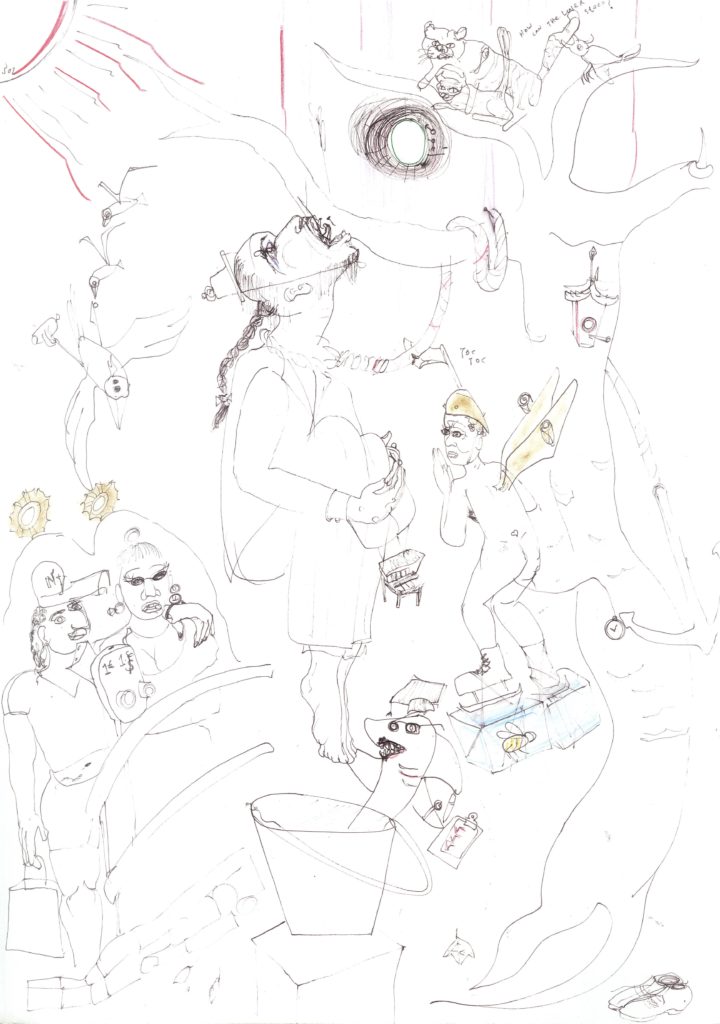

The drawing is from 2011, I made it for the Egyptian nude-blogger, teenage activist, Aliaah Maghda Elmahdy

Aphrodite. The poem is a fragment, the last stanzas of a poem I wrote about Greece during the crisis.

B.

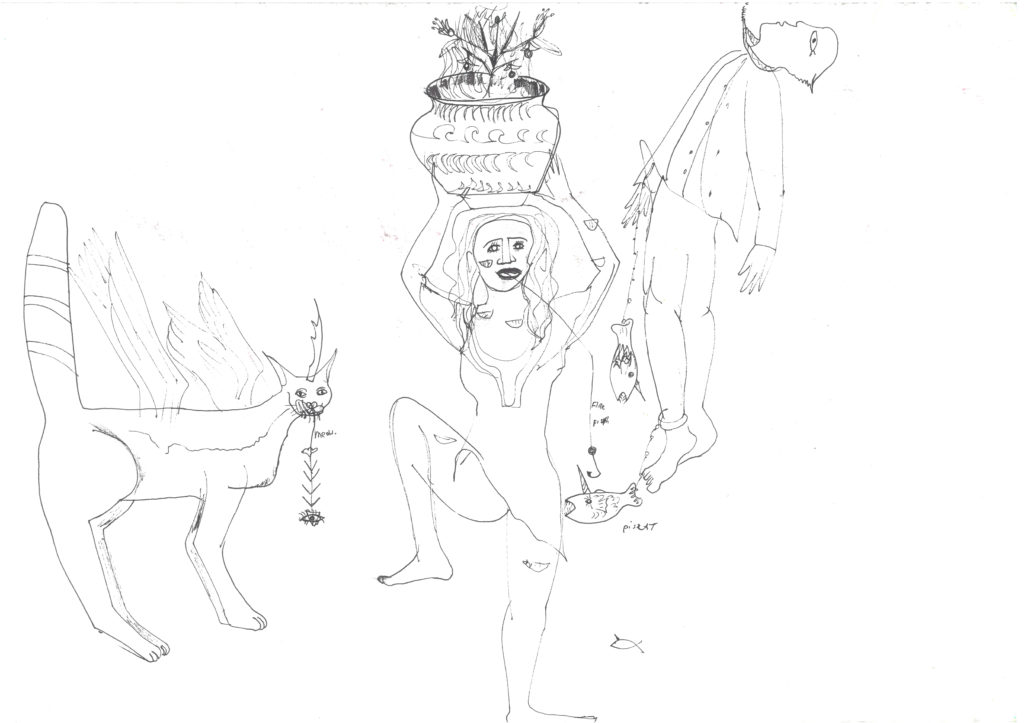

sistinacapelladream

Erotic and ecological poem (with anchors )

A woman levitates

bleeds a man.

Is filled in the sequence of days after

with holy lilies, a dropper from god into her.

goad

the blood turns white,

the brow darkens

with the mind, narrowing and becoming pointed

like a hat from on high

that makes the thoughts disappear, ( mistakes—(female word, mis- ) do reappear—)

A woman levitates

bleeds again.

(spoon-hipped recipe,)

the mother’s brain sails off

during pregnancy,

rolled up like a mast–

you cannot speak of that

in this age, or be brazen–

and do duck before

A mother’s brain

has the same shape as the clouds, but darker,

and her mind is as far as the cumulus

pouring through the basins, as Columbus

was from India’s chin

and her thighs,

the year of milk from heaven,

pouring through the cylinder of seraphic spring.

Never mind the calendars,

all lunar and never

and never again land(—man—you do sever, don’t you–)

Rituals rites hanged man Zoroastrian dancer woman andvisitor.

Rituals rites hanged man Zoroastrian dancer woman andvisitor.

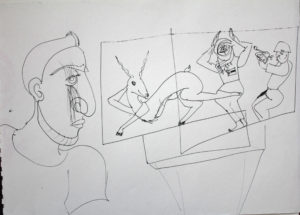

C.

Holy Land Cinema Regueb Tunisia, 2012

An adolescent from the Tunisian mountain village

of Regueb, looks on an outdoor movie-screen at his friends’ first short film, where they

reenact the dramas of the Palestinians. (A beautiful schoolgirl from the village, a gazelle, plays a victim of the Israelis

in the short-film.)

I first travelled to Tunisia in 2011, hoping I would become some sort

of literary correspondent like those writers who went to chronicle the Spanish

revolution in the 1930s (Albert Helman of Surinam was one such literary correspondent,

less known than George Orwell’s ”Homage to Catalonia”)–no such glory.

I visited a film festival upon the invitation of my friend, a Tunisian film-maker

from Sidi Bouzid. The festival took place in a rather impoverished, once forgotten town

of Regueb in the mountain outside Sidi Bouzid city, where the famous revolts started.

The international festival was supported entirely by the townspeople, many of them

jobless, as well as the artists who visited–musicians, theatre groups, film-makers and visual artists.

Posters with the face of Mohammed Bouazzizzi hung everywhere, even outside bullet-holed buildings: the fruit-seller’s

public act of suicide had catalyzed the revolution.

At an open-air, nocturnal screening, cinders from bonfires flew and met with fireflies over the heads of the audience,

as the jury announced the award for ”first short film” to a boy of 15 from the village. Men in denim stood up

howling and applauding in the make-shift auditorium for the boy who had directed a film about Palestine and Israel with his friends.

The adolescent camera-man, who accepted the award on behalf of his friends and Palestine

had never visited Palestine or Israel. Later he told me how his brother, a militant

activist, had hidden in a garden, pursued by the Tunisian military police and snipers who wanted to execute him

or torture him.

In the film he recites a long poem to music, wearing a kaffiyeh: he is a Palestinian,

running from Israelis, who shoot dead an Arab woman with powdered-grey wig,

as she sits making dresses on a Singer sewing machine.

It all seemed a re-telling, with a poem voice-over, of what had happened

to them in Tunisia under the dictatorship, but they changed Tunisia to the name

of a more relevant country, Palestine: a holy land, just as arid, with as many olive trees

as their fields. I found it at once mesmerizing and ironic: how the moment a talented youth

of this village had the means to express himself, instead of telling the story of his and brother’s lives

in Regueb, he would make another homage to the Palestinian struggle as if that were closer: to towel

and wrap the tale of him and his family in an arid unknown town in the Atlas, with Palestinian kaffiyeh

scarves and flags, covering the faces that utter poems with ravaged doves and daughters in them.

Perhaps that seemed safer: more distant, more in tune with the kind of expression of discontent that

was tolerated under the African regime they had so recently toppled.

D.

A hanging man does not plummet

Vodu Wolf, 2014