Black Americans got involved in the Punk scene during the ethos of the mid-seventies, just as Fusion, Disco and early Hip-Hop were going through a nexus and a simultaneous disbanding to stand on their own accord, distancing themselves from one another as they crossed paths at the intersection of Black American music.

Ramón Singley II on Black Punk

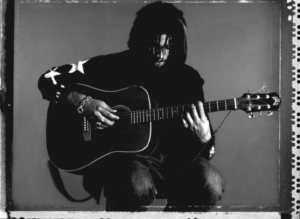

Benatural member Bruce Hatcock

BLACK PUNK

Sub Humans, Chelsea, 999, Dead Boys, The Cramps, Discharge, Black Flag and The Clash. These are just a few of the voices of Punk music’s lineage from the nostalgic early days; throwbacks some of which are forgotten, some not so forgotten. All the while, we’ve all seen the perpetrators and purveyors of this seemingly somewhat mythical ideology; the Mohawks, the black garb, spiked jewelry and in some instances, a total, over the top, all black get-up with a starved, heroine-chic look…Some are appalled upon first glance, while others look and stare with wonder. Moderately, or at some point or another, we’ve harbored an opinion, otherwise. And despite the bodily modifications, cigarettes, otherworldly appearance and far-left, misunderstood lyrics, Punk rock is and has long been a legitimate contender in the music scene with all of its honesty, boldness and just pure havoc. This is, in fact, Punk, as we commonly know it… Today, however, we will examine it a bit further, as Black Americans contributed to the Punk scene in a way most are not even aware of. A character study of sorts, Black Punk was a vision of authenticity, immersed in the annals of the history of music.

*

I was a novice to the Punk scene, so I started prying. After speaking with several gutter punks, I had an in-depth conversation with avid punk listener and Northern California native, Alan Hamm, who’s lived in L.A. for the past ten years, “…there are a lot of messages going on in Punk,” he says. “UK Punk has always had hardcore and extreme in your face messages…anything from sex and drugs, to making people know what’s going on in the world that people ignore altogether,” he says. “The Punk scene in LA is known on an international level. People are aware of what happened in the past here and see what’s happening now.”

*

D.I.Y., a popular saying in Punk, refers to an urging for one to “Do It Yourself”. Much of the music and production was always done on a shoestring budget, barely scraping by. Most of the bands never made much money, but the love of the message led a charge driven by pure passion as real music; a journey and rebellion bottled up in a Punk Rock message that was to be very honest and sincere. How were these creators and visionaries to stand up for their authenticity? The answer: whatever it took, it was to be finished no matter what. It was up to you and thus the meaning of D.I.Y was born.

Long considered a genre embraced by young outcasts and progenies of the Caucasian class throughout the United States, Australia and parts of Europe in the mid 70’s, Punk indirectly had a crossover influence and piqued the interests of bohemian, alternative-minded Black Americans who had an inclination to look for things that were different and contrasted what most typically associated with the culture. Black Americans got involved in the Punk scene during the ethos of the mid-seventies, just as Fusion, Disco and early Hip-Hop were going through a nexus and a simultaneous disbanding to stand on their own accord, distancing themselves from one another as they crossed paths at the intersection of Black American music. Fusion was left to only be embraced by the jazz purists who had the ability to cross over and see beyond classic jazz, as the once brooding sound was going through a transition into a more exotic phase, one of which was often referred to Acid Jazz. At the same time in the seventies, Disco was considered the most popular genre of music in the United States; a shooting star and short-lived all- enveloping apogee that crossed boundaries of race, sex, gender and all that proved to be happy and free and wild. The top was off, the girls were happy and everyone was on their way to a daylong remembered.

*

But at the same time, Rock purists and followers didn’t swoon to this. There was a massive backlash within the Rock community. Disco was a climactic enigma that as the eighties approached, everything abruptly stopped, sort of like the girl you saw in passing that you ogled and contemplated approaching, but after turning your head for just a moment, you looked back and she was gone; inexplicably vanished into thin air, while you were left shrouded in regret for not talking to her. So why did this happen? Far-right thinking could explain it, as “Disco Demolition Day”, Thursday, July 12, 1979 in the middle of a baseball stadium at Comiskey Park in Chicago hundreds of disco records were brought out to the middle of the stadium and subsequently burned, culminating with a riot. It was the epitome of love vs. hate.

“Some felt disco was too mechanical; TIME magazine deemed it a ‘diabolical thump- and-shriek’. Others hated it for the associated scene, with its emphasis on personal appearance and style of dress. The media emphasized its roots in gay culture. According to historian Gillian Frank, “by the time of the Disco Demolition in Comiskey Park, the media … cultivated a widespread perception that disco was taking over”. Performers who cultivated a gay image, such as the Village People (described by Rolling Stone as “the face of disco”), did nothing to efface these perceptions, and fears that Rock would die out after disco albums dominated the 21st Grammy Awards in 1979.” Disco, in its own way, was Punk, too. It struck nerves and caused angst, while at the same time created ineffable joy, in what I’d consider one of the more perplexing epochs in music history.

70’s equipment, photo author

As for the boundless and determined Hip-Hop, even though Afrika Bambaata and the Sugar Hill Gang were setting the foundation for the likes of Public Enemy and N.W.A. to be, early contemporary Hip-Hop of the early to mid-eighties was in many ways just as volatile and violently contagious as any Punk song. In many ways, the not as pretty girl who was super sexy with lots of style and confidence was crashing the Punk party next door. But to some, Hip-Hop was Punk. Ask Rick Rubin. He swore Public Enemy was actually a Punk band, and a hard sell, once asking Russell Simmons what he was thinking when he first considered them for the historic Def Jam record label. Early on, many Hip- Hop acts were risqué and lyrically thought provoking, pushing the boundaries of topics involving politics, sex, violence, drugs and oppression, similar to many Punk mantras then and now. These purveyors and founding fathers of Hip-Hop’s genesis pushed the boundaries and limits, as early practitioners and pioneers of most art forms are typically wont to do. In doing so, the early records of the hardcore east and west coast acts were considered somewhat Punk in nature by those who were privy to Punk standards and for those who saw these similarities aptly known to them as Punk. So yes, mid-eighties Hip- Hop was, in fact, and in many ways Punk, believe it or not.

*

But even before we can take a look at these Hip-Hop acts, we have to look deeper into the mid-seventies at mostly Black American pioneering Punk bands like Death, Pure Hell and Bad Brains. Cumulatively, they received moderate acclaim outside the bastion of the Punk universe, yet within the construct of Punk, they were known as some of the purest hardcore practitioners of the genre; the first of their kinds, compared to the sounds of Disco and early Hip-Hop of the time which often left conservatives throughout the community perplexed. Those mid-seventies bands were to Punk what the Ultramagnetic MC’s, Run D.M.C., L.L., NWA and the Native Tongues were to Hip-Hop. And despite the racism and resistance that existed on the periphery of the genre, theses early bands miraculously pushed through and made the music be heard.

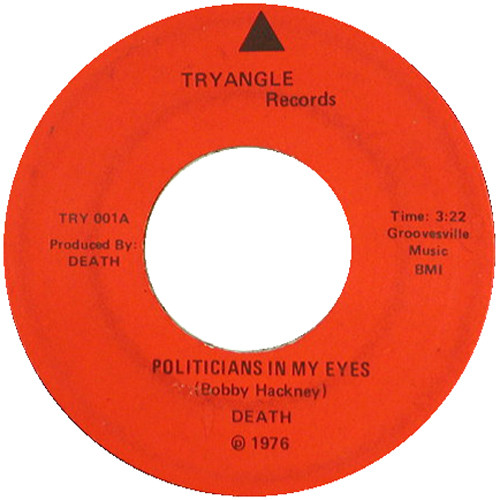

Death, the hardcore pioneering Black American Punk outfit comprised of three brothers hailing from Detroit, were an exception to the rule. They were Punk to its core; wild and crazy black dudes, skinny with wild hair, screaming into the microphone with something relevant to say for those closely listening. While mostly obscure for the past thirty years and only known to the truest Punk collectors and purists, Death popped up on the radar back in 2009 when their self-released demo tape was re-released for the first time since 1976. Their demo tape single sold for $800 to an undisclosed collector of fine music. While Death is known to true underground Punk heads who rocked out during the seventies and for hardcore kids since, they most likely would have stayed in anonymity to the mainstream and collectors, had it not been for this rare discovery in the attic of Bobby Sr., one of the 3 brothers. Subsequently, the demo tape was re-released by Drag City Records as, For the Whole World to See. The discovery of these recordings casts a new light upon their prowess and link between the high-energy hard Rock banks of Detroit like MC5 and The Stooges from the early to mid-seventies. It shows the prowess of Death, as they hit the music scene 5 years ahead of the most revered Black Punk band of all time, Bad Brains. To many, Death was the standard.

*

Today, predominantly Black American and other global bands whose work ventures towards Punk, don’t even mean to classify themselves as Punk. In their minds, it’s more effortless, as they just happen to be Punk in nature. Despite their perspective, they still get prescribed. “I am in Punk Because I got put into Punk, but I consider myself in Hip-Hop too” says William “Ambush” Nicholson of the L.A. based outfit, William & William, Inc. “… I liked N.W.A., early-nineties Hip-Hop, The Doors, and all of that, but people put you into this Punk category and other categories for that matter. A lot of what new music people are doing just automatically gets put into different genres. When I do music, it’s just music, “ he says.

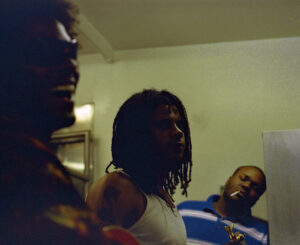

The band Benatural, photo the author

TCIYF (The Cum In Your Face), hailing from South Africa, or Big Joanie, hailing from the U.K., are two bands on the international Punk scene, who despite racism that still exists in the music, still push through as determined outfits on a mission to be heard.

“John Doe, bassist and a founding member of the band X, witnessed the rise of fascist attitudes in the hardcore scene first hand, and saw it as a bastardization of what attracted him to punk in the first place. The entire essence of being a punk was, as he puts it, ‘never letting someone tell you what to do.’ But somehow factions of the hardcore scene managed to flip that notion on its head to the point where it creates angst. If you don’t look and act like us, get lost.”

*

Having taken the baton from the seventies and eighties purveyors of Punk, these international and stateside bands have staved off epithets and infiltration of neo-Nazis and other racists who for some strange reason don’t see people of color contributing to the music. But this is part of the Punk way; determined cohorts who band together against a fight, whether it be politics, racism, drugs or even personal tragedies and demons.

*

According to Nicholson, he and other Punk(ish) contemporaries frequenting the L.A. area such as Emani Fela, Piel, Blackbirds and Richard Ray the Square Disc Jockey don’t even consider themselves 100% Punk. They just happen to get classified that way. Similarly, this dilemma of being classified within constructs of music can have positive and negative effects. For instance, Tyler the Creator expressed frustration when he won a Grammy for “Best Rap Album” despite the fact he doesn’t consider himself to be a Hip- Hop artist, per se. Getting classified in the “Urban” category is a complete mishap because he doesn’t think of himself in an “urban” sense. His thinking and his way is not “Hip-Hop” or “Urban”. To me, he’s a Punk kid with style, grace and a unique voice. These umbrella terms exist for many artists. Some are okay with it, others not so much.

Collage by the author

“It sucks that whenever we — and I mean guys that look like me — do anything that’s genre-bending or that’s anything they always put it in a rap or urban category. I don’t like that ‘urban’ word…” Tyler says.

Punk is a mindset. It’s a music aesthetic, that when coupled with one’s ideas and messages, culminates in a sound. To a degree, we all are Punk, indeed. Our beliefs, mantras and aesthetic define us. To Tyler and other musicians, this is a Punk sort of issue; a rebellion, a validation, a fighting for one’s right to be free with their music. To them, their music is Jazz, rock and everything in between. No frills. Yes, there are the classic influences factored in, but in the end, it’s just music to them. Some embrace categorizing, while others are more averse. Maybe they’ve evolved in such a way they are ahead of their time, basking in the cache of the alternative prior to a huge music revival. But come to think of it, this always seems to happen in music. It happened with Bad Brains and Death. Someone opens up ears with something totally new, while most don’t seem to have a clue, not hearing the lyrics, only intrigued or damned by the drum. Suddenly, someone of stature validates its premise and the next thing you know, someone is a genius, sitting back laughing with a cocktail in hand on vacation in Positano or sitting for an interview in front of The Viper Room in Hollywood with their chest hairs poked out, while having all the answers to all the questions. It always happens this way.