Through their art work, these women confront the injustices of misrepresentation done to black women throughout history and disrupt the built-in prejudices they have faced. Importantly they also prove that the importance of black female’s bodies run more than just skin deep.

Christabel Johanson on Black Women’s Bodies in Art.

First published: September 3, 2019

Black Women’s Bodies in Art

Women’s bodies have always created a stir within society, especially from the seeming contradiction between female sexuality and motherhood. Often called the “Madonna and whore dichotomy” this ambivalence makes the site of the female body a contentious spectacle for men and women alike. Add to this mixture the sight of a black female body and the racial context it elicits, we find ourselves in the middle of a textured conversation about womanhood, race and inevitably society’s opinions upon it.

*

“The Male Gaze” is a phrase known in feminist theory relating to how women are depicted in literature, cinema, art and wider society. The gaze is assumed from a cis-gendered, heterosexual masculine perspective. It commonly objectifies women, represents them as sexual objects or objects of desire for a man. The term was coined by Laura Mulvey and takes the perspective that the male is behind the lens, or within the audience. Applying this to black female bodies can also transform black women as the object of fetishism or racism, assuming the male takes up a seat of ultimate privilege (i.e. whiteness) as well.

*

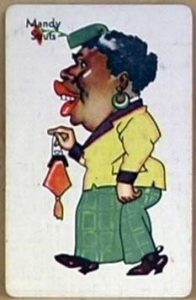

Socially this renders black female bodies disempowered towards their depictions on-screen, in books and in art. The impact on wider society is an imbalanced perception of black women. For instance the “Mammy” archetype presented black women as plump older figures with caricatured facial features in order to create a matronly, desexualised and racial rendering of black women. Historical cartoons of black women have also exaggerated their figures to hyper-sexualise them as nymphomaniacs or look more animalistic or ape-like.

The Mammy stereotype

These images essentially create an anti-black attitude, a threatening sexuality or position black bodies into servitude. Within a political context black females have been treated unfairly through social injustices. Take for example the attention white missing children have (Madeline McCann for instance) compared to black children. This disparity was highlighted when the #BringBackOurGirls campaign was in full force in 2014 when 276 Nigerian girls were kidnapped by the Boko Haram. However these campaigns fade quickly from the minds of society.

*

Going forward to today, artists are leading the reclamation of space for black bodies – particularly female bodies – in order to challenge audiences to think about them in a different way. As an object of art, the figures have a relationship within the art work itself, a relationship to the artist and a relationship to the audience. These are the dimensions in which the artists are able to play with the Male Gaze, shape the perceptions of blackness and speak about wider social contexts. There is also something to be taken from the fact these artists are themselves female and how their lives and art imitate each other.

Does one’s own gender and identity feed into the work? In cases like these I think it would be difficult to separate art from artist, which gives an authenticity to the pieces. This is especially true of Lesley Asare’s piece discussed later. Being a woman in the art world is as challenging as it is with any sphere where men still dominate. For instance there are still only a small percentage of female artists featured in key art galleries within Britain, such as the Tate Modern’s collections in which only 35% of works are by female artists .

Therefore the spotlight here will focus on three artists who are shaping the conversations about black female bodies; Harmonia Rosales, Sola Olulude and Lesly Asare.

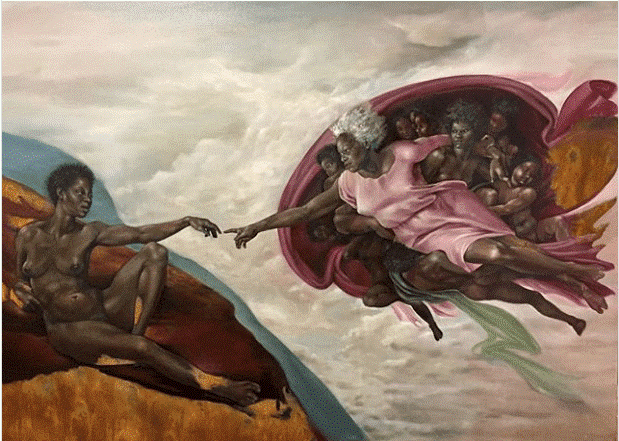

Harmonia Rosales

Rosales transforms classic pieces of art into black-led visions. For example she repaints The Creation of Adam by Michaelangelo to show God as a black woman. Rosales, who is of Afro-Cuban descent, places women of colour into these famous recreations in order to stretch the viewer’s understanding that humankind is not just the white, male representations that have always been shown. Her remake entitled The Creation of God replaces all the figures as black women and so deconstructs the dominant European theology of a white male God and angels. It also challenges the standards of the “ideal” human body and standards of beauty of Adam as a white man. It also harks to the modern understanding of humankind originating from Africa and the importance of maternity in mankind’s story.

The Creation of Adam, Michaelangelo

The Creation of God (2017), Harmonia Rosales

In the body of her work there is a deeper message of how power, misogyny and beauty are dictated, from where and why. Historically white aesthetics have seeped into the arts, culture and religion and Rosales’ work helps to unpick this – and even though the portrait has invited controversy it is a necessary thought-provoking milestone.

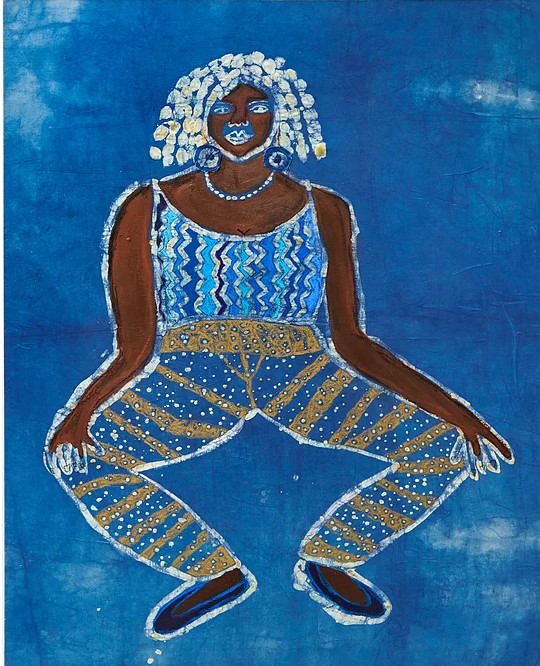

Sola Olulode

Sola Olulode, a Nigerian-British artist who hails from Brighton, portrays black women within the themes of friendships and happiness. Olulode works with blues which create a calming effect on her pictures. This blue colour is from Adire, an indigo-dye material, made traditionally by Yoruba Nigerian women. Olulode says that the blues also “confront the whiteness and white walls in art institutions”. The colour also contrasts with the darkness of the women’s skin, thus highlighting their black identity further. The paintings are dreamlike due to their ambiguous-looking gender presentations and sexual identities which Olulude describes as fluid, and as such positions them also for a queer or LGBT reading.

And you Sabi do the dance well (2018), Sola Olulode

Looking good, feeling good (2018), Sola Olulode

Featuring these black female bodies at their centre, Olulode shows the beauty of its form through dynamic or celebratory poses. These movements show the women to be victorious, happy and dancing in joy – a departure from the aggressive, masculine or tormented figures that black women have been presented as in the past.

Lesley Asare

Lesley Asare is a British Ghanian artist whose belief is that creative expression is therapeutic and through her work explores the history and experiences of black women. She aims to “create a space for play, self-reflection, self-awareness, empowerment and healing”.

*

In her project entitled I Shape Beauty she asks the question “when you look at your body what do you see?” For Lesley herself the answer is “Shapes and curves. Different shades of brown. Scars and blemishes. I see myself”. For this project, captured in a series of photographs, Lesley wears a “costume” that lifts and shapes her figure (similar to body contouring suits that are available in women’s department stores). Through the course of the series she peels away each layer to draw closer to her most authentic final form.

Here we question how Western standards of beauty fit into a black woman’s physique, using Lesley herself as the canvas. Being a thicker female, she is not a size zero and so the binding of her body conflates both the absurd standards of body shaming, as well as contrasting it with her female shape. From the sides of her costume she pulls out a tribal cloth that represents her racial heritage. This becomes a headdress with which she adorns herself. As the costume is stripped away and transformed, Lesley slowly recreates her outfit into a new dress. In this project she theatrically demonstrates that from the bindings of society, (black) women can emerge from it with their own culture and identity celebrated, exemplified by the affirmation in its title “I shape myself”.

I Shape Beauty, Lesley Asare

These artists have worked to strike conversation about how black women’s imagery has been distorted in society by reshaping and reclaiming these representations for themselves. By demonstrating what their bodies can represent – be it their curves, their happiness, or their own historic value – divinity, ancestry and physicality are drawn out through these artist’s work.

*

In these ways, what is achieved is not only a fuller, richer stake in society but a subversion of a traditionally biased perspective (the Male Gaze) that has historically been dominated by men and whiteness. Through their art work, these women confront the injustices of misrepresentation done to black women throughout history and disrupt the built-in prejudices they have faced. Importantly they also prove that the importance of black female’s bodies run more than just skin deep.