“Well you know, sometimes I get so irritated with audiences, especially male audiences who will say stupid things like “that’s a nice ass” or something like that. For me, I think as long as the performer knows exactly what the intention is with the body everybody will get over everything else. There are some people who just don’t get it, and that’s ok too. I know what my body is loaded with. I know what it is and I know how to use it. I know I’ve gotten to the point where I know how it works. I don’t necessarily care anymore.”

Buhlebezwe Siwani in conversation with Candice Allison.

Buhlebezwe Siwani

I am a performance artist, but I don’t want to just say, that’s it.

Buhlebezwe Siwani was raised in Johannesburg, South Africa. Due to the nomadic nature of her upbringing she has also lived in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu Natal provinces. Working predominantly in the medium of performance and installation, she includes photographic stills and videos of some performances as a stand in for her body which is physically absent from the space. As a practising isangoma, a traditional healer and spiritual diviner, Siwani performs the creative and sacred rituals that inform her history, identity, and politics. She completed her BAFA (Hons) at the Wits School of Arts in Johannesburg in 2011 and her MFA at the Michaelis School of Fine Arts in 2015.

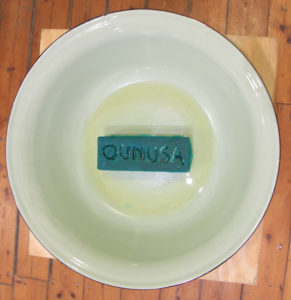

Qunusa! Buhle, 2015

I caught up with Buhlebezwe at her studio at Greatmore Studios in Cape Town. She dons a blue overall jacket and while we talk she grates long bars of green soap, an inexpensive multi-purpose household soap generally used in South Africa’s low income, predominantly black households. Spread out across the floor is an assortment of yellow and white enamel bowls, into which she has moulded the soap into different forms, in preparation for an upcoming show, Skattie Celebrates Buhlebezwe Siwani: Ingxowa yeGqwirhakazi at WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery. The chemical smell of the soap punctuates the air as we talk; she keeps apologising for this, but it is a pleasant smell, like the sharp tang of green lemons. We have very different childhood memories of this soap, something that reminds us of the two South Africa’s that we grew up in: mine an urban, ‘white’ South Africa and hers a mostly rural, ‘black’ South Africa. The only connection I had to this soap was standing in the checkout line at the supermarket, sometimes behind a black man, usually wearing the blue overalls of a labourer, holding in his hands a ‘half loaf’ of white bread, a 1L packet of milk and a bar of Sunlight soap, while around him white people might discreetly – or in some cases not so discreetly – cover their noses, offended by the smell of a man who had been physically working hard all day, in the hot South African sun; a man who could not afford the luxury of deodorant, fancy soap, or washing powder for his clothes, and who would most likely go home each night and bathe himself from a bucket or an enamel bowl of water just like the ones spread out before us. Her memory of the soap is at her grandmother’s house, where it was used for washing clothes, dishes, cleaning the house and as part of a humiliating routine of body washing – her grandmother would scrub her down while she stood naked, often in front of family or guests who were sometimes male. She dreaded the point when she would be told to ‘bend over’ so that her ‘dirty places’ could be cleansed and purified. This daily routine was something reserved for girl children; she never saw a boy being washed in this way. The emotion we both share around these recollections is shame.

The conversation is at times interspersed with the crackling of plastic packaging as she works her way through the bars, and at one point we distract ourselves comparing the different shades of green that emerge with the grated pieces, even though the bars look exactly the same on the outside. Lively music drifts through the walls when the artist in the adjoining studio arrives.

Qunusa! Buhle (detail), performance, 2015.

She talks a lot about not caring what other people think – it could come across as abrasive, or even a case of ‘the lady doth protest too much’, but as we talk I realise that she has reached a reflective and accepting approach to her practise, a confident self-awareness. She creates work first and foremost for herself.

CA: You’ve just returned to Cape Town after travelling for three months. Where did you go and what did you do?

BS: I went to Switzerland initially for the Swiss exchange Pro Helvetia Residency, which basically is an open residency, you can do anything. My residency was at Rote Fabrik in Zurich, so I decided to create work about the kind of relationship that the Swiss have with South Africa and the fact that over 90% of South African gold is in Zurich, that’s where all the banks are. Also the interesting thing is that Switzerland has never colonised, neither has it been colonised. So I decided to make performance pieces around colonialism and that kind of relationship that Switzerland has with itself, with Europe and with Africa. I also did work on the last witch that was burned, especially since I work with matters of spirituality, and the last witch that was burned was in Switzerland. The series was called Black Heidi. I did impromptu public performances where I didn’t tell anyone, I just arrived in the space. I did four performances like that, two about the witch burning, and the other two were about the gold, colonialism and human capital.

Black Heidi, 2016, performance in Zurich, Switzerland.

CA: Is that gold that we own, or that the Swiss own?

BS: It’s owned by different people. More than 50% of the gold there is owned by the Swiss, but the rest is kept for other people. They also kept money for the Apartheid government, and they still have it, so yeah. They have Gaddafi’s gold, Mugabe’s gold is also there. There’s a lot of interesting stuff. But you know, they are neutral, or they say they are neutral.

CA: How were the peformances received?

BS: Besides going for the residency, I was invited for a performance festival called Theater Spektakel, where I was one of the short pieces. I was nominated for a prize. I didn’t win. It doesn’t matter (laughs).

The performances, I had a couple of people cry, in the Theater Spektakel one, but in the impromptu performances, well, the Swiss are very conservative, so they’ll just look and they’ll pretend like they can’t see what’s happening, but you’ll get a lot of tourists, in one of the streets I went to, they were very interested, they wanted to take photos, and I was like no, I didn’t want to engage with that.

CA: Why did they cry? What do you think brought on that reaction?

BS: The first performance I did at the Theater Spektakel was basically around reparations, how we take back the land, and I used the student protests as the starting point. I started with video pieces of these different camps for Boere (Afrikaans) guys who run the camp because they think black people are going to invade and kill them all, and then I move on to the student protests, and after that I go to the land matter. It’s also about how the female black body is viewed in protests, how black women have protested certain things, and how they are kept out of protest history. If women must protest they must protest not to make a mark, you know, it’s not like you can be a part of the ANC and be there with Mandela.

CA: Yeah, you will end up being side lined.

BS: Always. So it was pretty emotive. And another thing I found out while I was in Europe, a lot of people actually don’t know what’s going on here. They have no idea. Meanwhile we’re busy praying for Paris. I don’t know how that’s going to help us. Paris isn’t going to pray for us.

CA: So this travelling is going to be part of your life now.

BS: Yeah, I guess so. Is this a question? (laughs)

CA: Yes, it is a question. Have you accepted that? And the people close to you, have they accepted those absences?

BS: My partner nearly had a nervous breakdown, when I told him I might be going somewhere else for a residency for five months, because I just came back after three months. I’m prepared for it; I’ve been ready for it. My mother especially has known that when I decide to stop being lazy and make art that makes sense, for me, and that’s honest to me, then I would probably not be around much. So I think she knew from the day I left Johannesburg for Cape Town that ok, I’m becoming serious. I think it was a happy thing for her, but also a sad thing, in that she won’t see me as often. I think she’s used to it.

Zemnk’inkomo Magwalandini, 2015

CA: I visited your Master’s show last year, titled Imfihlo (2015), at UCT’s Michaelis School of Fine Art, which included a variety of media including photographs, video, installation, and for the audience who attended the exhibition which was up for only one evening, there was also a performance. From what I understand you consider yourself first and foremost a performance artist, and I am curious about what role these other mediums play within your practise, and to your performances in particular. What is their connection or disconnection?

BS: No, I guess I got that title, but I’m an artist. Yes I do primarily do performance, my stills are performative even, my photographs are performative, my videos are performative, so I guess in that sense, yes, I am a performance artist, but I don’t want to just say, that’s it. I do many other things, I make stuff; I make installations; the photographs and the videos perform differently to my body in the space in front of you.

CA: The concept of your graduate show was around the idea of secrecy, what we choose to reveal and what we choose to conceal. Can you tell me more about this, and how this is reflected in your practise?

BS: Primarily it is because I am an isangoma, and it was around rituals and rites of passage in Africa, and how artists have worked with themes of secrecy concerning circumcision, virginity testing, and all of these very interesting rituals. Nobody has really interrogated ubungoma, being isangoma, and me looking from the inside and being an outsider in a sense, because I am making work about it so there is this kind of duality that needs to exist, which is basically how I’ve always seen my work. I guess the entire Imfihlo (2015) was about whose secret, why is it secret, and how do you preserve the secret, or how do you reveal the secret without revealing everything about it? What remains hidden and what can we show people? It was just around not saying too much but saying enough, and how you reveal it. Around that I was interrogating African religion and the female form. It became so nebulous, because as I continued to research and as I continued to make work it just became bigger than I anticipated. There is so much to talk about.

CA: Did you take a particular stance taken on how much is enough to reveal and how much is too much?

BS: No, there wasn’t a stance, I wanted to leave the decision to the audience, or whoever is seeing, but for me I know it was enough. I kind of figured myself what was enough to show people and what was not enough. Whether I like it or not, people normally say I’m making work for myself, which yeah, I am, because I can’t let other bodies speak for me.

Installation view from Skattie Celebrates Buhlebezwe Siwani Ingxowa yeGqwirhakazi, 2016 (Exhibition at WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery, Cape Town).

CA: And you can’t speak for other bodies.

BS: Yes, I can’t, so I wasn’t going to photograph other bodies, I was going to use my own. I wasn’t going to put other bodies in my video. I wasn’t going to put other bodies in my performance, but in the end I did actually, for the one with the scars, Zemk’inkomo magwalandini (2015), the one that you came to. But she was very aware of what she was doing. She came in, and there was a very clear purpose of why she was there. There was a reason why she was there, it was clear to me, it was clear to her, and that’s how we worked. And it was also clear to whoever was watching, why that person was there.

CA: We cannot talk about performance art without talking about the body. As a tool for engaging with your audience, the body – your body – is loaded with history, culture, violence, shame. What kind of responses have you had from your audiences, during and after your performances?

BS: Well you know, sometimes I get so irritated with audiences, especially male audiences who will say stupid things like “that’s a nice ass” or something like that. For me, I think as long as the performer knows exactly what the intention is with the body everybody will get over everything else. There are some people who just don’t get it, and that’s ok too. I know what my body is loaded with. I know what it is and I know how to use it. I know I’ve gotten to the point where I know how it works. I don’t necessarily care anymore. I can’t say I don’t care about the spectator because it is about the spectator, but I don’t care what many people think, because the moment you allow them, then you allow people to violate you again and again. I don’t want to be violated anymore. People bring a lot of their own things into how they see the body. It can just be too hectic, so I guess it’s also the artist’s decision. This is why I don’t like using other bodies, because other bodies can imply different things. You come in with your own feelings, background, and history. Even though experiences aren’t written physically on the body, the body is such an emotive tool that you can feel certain vibrations, if you are open to feeling them. I would rather just keep using my own body. I know what kind of violent places it’s been to and what kind of violence it’s been through. So that’s why I mean I understand my body, I would rather use it as a vehicle than other people’s bodies.

CA: Do you expect anything from your audience? Do you think your audience expects anything from you or from performance art in general?

BS: I think that audiences always expect. I guess it also depends on who you are, they expect to be wowed. I don’t really care, I just get on with it and do what I feel I need to do and if somebody doesn’t like it, I’m also ok with that. I’m here to just create and to add. I don’t really have expectations for the audience. I think sometimes they come in and try to just be pure spectators, but what they don’t realise is that when you sit there, you become an active participant in the performance. You become part of the performance. A large part of my thesis at that time was also about spectatorship, and the fact that spectators are involuntary participants.

CA: Do you ever create/recreate the same performance more than once? In the case of that performance, but in all of them, is there choreography, or a format?

BS: No, it’s actually a bit of both. So I sit down and I let her know what the idea was, ask how she feels about it, what she would like to do, and if I feel like I could incorporate that into what I’m doing, then it comes in to the bigger idea, we see how we can fit it in. If not, then it goes. It’s really that simple, because it’s not her piece of work. I like the whole process to be very organic, so whatever you feel like you’ve come up with, let’s think about it.

CA: And then do you recreate performances?

BS: I do, there have been two that I’ve been asked to recreate, but they never actually work in the same way. They’re always really different. I think space changes a lot of things. It never really works the same.

CA: Your works obviously originate from a personal and subjective narrative. Does this help you work through moments in your past and your present, or does it create more tension for you to re-enact these emotions?

BS: No, I think it’s become a cathartic process for me, where I get to figure it out over and over again. Sometimes a lot of artists go back and they think, that’s embarrassing (laughs) that work that I did then, and after five years of practising I can also go back and ask myself, why did I do that? I’ve never had that moment where I’ve felt embarrassed though, because everything I’ve done has come from an honest place. I can go back and say I still feel that way sometimes, and its ok. I still understand what’s going on there. So I want to live in that emotion for a while, and I want to know that this emotion existed, or that this journey happened.

Zemk’inkomo magwalandini, 2015, performance at Michaelis Galleries, Cape Town.

CA: Are there any performances that you just would not want to do again? It happened, it was done, and it lives in that place.

BS: Yes, there are two performances that I think, let it live there, by itself, it will not happen again. One was iJoowish (2016) that I did for Live Architecture: the 55 Minute Hour in Salt River, earlier this year, during Art Week Cape Town. I don’t think I would ever want to do that again. I don’t want to revisit it, because I feel that it’s done.

CA: Your use of language – titling your works in isiXhosa or isiZulu – It’s also a conscious decision about what to reveal and what to conceal depending on who your audience is.

BS: Yeah exactly.

CA: Language has been used as a powerful tool for exclusion in our past, and even our present.

BS: Well I mean, the whole point of that was, South Africans embarrass me. You are born here, and yet you can’t speak one vernacular language is an issue for me. You’ve had the chance, I mean you are surrounded by people, are you telling me that as a white person you are honestly not going to make that effort. I know how to speak English, I wasn’t born around people who speak English, and I was born around people who speak isiXhosa, isiZulu. Yet I know how to speak seSotho, which is totally different from my own language, and you are telling me it’s difficult to speak one. So I’m just not buying it. I’m not interested. I title my work in a language that resonates with the work. It is also to exclude, because I know you can’t speak it, and I know that most of the audience coming in need a translation, which forces you to engage with the work even further. So it’s also a conscious decision – it might be a bad strategy, but at this point in time I don’t really care – I’m going to continue doing it.

CA: Get a dictionary and learn?

BS: Yeah, exactly (laughs). I feel like you could make an effort, you know, but people don’t make that effort, so I also feel like why should I? Also the work is so close to what it is that honestly I feel like I don’t want to tear it away from that, I need the work to remain as honest as possible. I kind of have this insane puritanical obsession with the work, it must just exist. I don’t want to overcomplicate the work because as it stands, the work itself is complicated, so I would rather simplify it and keep it real.

CA: Do you ever use your voice in your performance work?

BS: I used it once, when I was in Berlin, I sang. But I know how to sing. I was part of a band.

CA: Really? What band?

BS: Now you’re asking questions. A band, just a band. It still exists. A soul funk band. I can sing. I just don’t like to. I actually did two performances where I sang, once in Berlin and once when I came to Cape Town, it was my first performance actually. It was at Theatre Arts Admin in Observatory.

CA: Does that make people feel like they want to applaud?

BS: I don’t even know anymore. It’s so weird, how people kind of change modalities between ‘this is art, and this is theatre’. It was a directed piece, not that art isn’t directed, I mean Tino Sehgal, there are artists who are active directors, but you know Cape Town theatre, they like to say who it was directed by. So I kind of just decided that it was not for me. Also I don’t like being told what to do by people.

CA: The work you produced for the group exhibition The Quiet Violence of Dreams at Stevenson Gallery.

BS: I had two works. One was the performance.

CA: Ok, so the performance, it was done in private and not for an audience. Why did you choose this strategy?

BS: I don’t think everybody needs to see the performance, like Joseph Beuys did a performance by himself, he didn’t let anybody in. I just felt that I didn’t need anybody, it was about solitary confinement. It was called Umthakati Akalali (2016) which is basically ‘the witch doesn’t sleep’. It was just me sleeping in the gallery for 24 hours without speaking to anybody.

CA: You staged a performance at Njelele Arts Station in Harare, Zimbabwe, earlier this year that reflected on your relationship with your mother and your grandmother. Can you tell me more about it?

Indlovukazi, 2016, performance (detail) at Njelele Arts Station, Harare.

Same performance (detail) in Harare, 2016.

BS: It was called Indlovukazi (2016). My grandmother got really sick after my other grandmother died, they were sisters. She had beaten cancer twice, and she had no cancer, no tumours, she just died from a heart attack. Then my grandmother got sick and nobody could figure out why. I think it was just down to, she’s broken now, it happens, when someone has a relationship like that and that person is no longer there, they give up. It’s time for them to go as well. My grandmother is getting ready for her death; she’s just preparing the rest of us. The reason why she’s still here is because there are people who are struggling, and she’s just here to make sure that by the time she leaves, they’re fine.

My mother was diagnosed with depression in her early twenties and she sometimes has suicidal thoughts. Recently she was diagnosed with diabetes; she has difficulty seeing now, so it feels like death is just around the corner. She felt like I should prepare myself for her death and for my grandmother’s death as well. So the conversation was around what do you tell your black daughter? It was around them not being around and what they would have told themselves when they were younger, about how they raised me, and why they raised me the way they did. Also, because my dad is not completely black, it was about being the type of black woman that I am. My mom was never too sure what to do with my hair, and even though I’m a black woman they would question certain things about me being her child – why do I look like this, why do I have hair like this, why are my eyes the colour that they are, why are some of my features like that – my mom was never one to want to explain those kinds of things, it’s the way that she is – but it was about me coming to terms with the fact that I have a mixed heritage and I have to accept that. It was me not being ashamed of not being black enough. Yeah, so I had a conversation about blackness, with my grandmother and mother, and if they left me, what is the legacy that they would like to leave behind?

CA: That’s quite emotional.

BS: Yeah, it was, it was a very intimate performance.

CA: And it involved typing letters?

BS: Yeah, typing letters to each other, love-hate letters, like “I remember when it was this day, and I hated you for this”. It was very personal, but the thing is, I invited the audience in, what would you tell your child if this had happened, so it wasn’t like the audience wasn’t out of it completely, they were also part of the performance, because you know, someone in Zimbabwe is the parent of a black daughter, so tell us, what would you tell your child?

CA: From what I understand, you were brought up in a very strong matriarchal household. How has this informed your practice?

BS: A lot. In this strong matriarchal household, I was never really told what to do. I just kind of went about my business and it was like “you’re so wrong and you know it, so we’re not going to tell you that you’re wrong, you know it’”. Also my grandmother worked for children’s rights.

CA: So she had a firm belief that children knew what they wanted?

BS: Yeah, I think she was very right. You know, with kids that age people think that we need to do everything for them. My grandmother did jack diddly squat, she just washed us. If we didn’t get home by six or do our homework, my gran would just say that’s on you, if you don’t do your work and you start failing, I’m not paying for school fees. This is how it worked. It was a house where kids respect the elders, elders respect the kids, and you don’t get beaten, you would sit down and talk. Oh, but my mother was the complete opposite. She will beat your ass first, and then she will give you a lecture. So I grew up very differently with my grandmother. When my mother came back, because she was gone for a while, it was very different. My mother was a hip woman, she was a magazine editor, a journalist, and then she worked for the entertainment industry. I used to get babysat by celebrities.

I think it informed my work in terms of sensitivities, but also allowing things to speak for themselves. I mean, people do way too much. The simplest thing, I could literally just have an exhibition by putting this bowl down. For me, that would be enough. But for some people they’ve always got to go extra, extra, extra. I don’t feel the same way. And I think that’s largely because of growing up with these women where everything was simple and it wasn’t too much. It was dramatic in the way it was lived out, not seen. Those two things are very different things, but they can exist in the same sphere. Those are the kinds of things that inform my work. And also, growing up with them, they are wells of information. My partner is also a well of information, so whenever I have something to ask, I ask my mother first and then I ask him, and I put something together using those two things.

Also, I think being with these women and also having a very male family – my father’s side of the family only has four women, I’m one of them, and the rest are just male. Even the women are giving birth to boys.

CA: So you had to be a strong woman?

BS: Not strong. Dudes are dudes. But there’s also an understanding of how men are. Especially cis het men. And there’s also an understanding of how cis het women are. I have an uncle who is gay that I used to live with for about a year, he and his partner were very ostentations, so they used to take us to places where I got to see cis het men, queer men, but also queer women, through him, and through my mother – working in the entertainment industry, not everyone is straight – so I got to meet a lot of different types of people, and I also discovered my own sexuality through that, and I got to discover that I’m really comfortable with my sexuality, not being gay, not being straight, but just liking human beings.

CA: You are also a member of a black female collective called iQhiya. Has this had an effect on your personal work?

BS: Yeah it does, I really, you know for a minute there I hated the collective because I couldn’t pay attention to my work. I can’t say they spring-boarded my career because they really haven’t, it’s just that I add a different dimension to the collective. It’s really good to sit down and reflect with the collective. People think it’s just about making work but it’s not, we have conversations about things. We have fights about things. We exist as people who get mad at each other because we’re all friends and as time goes on we find ourselves at this point where if one was to leave it would be ok, but we’d still be friends. Yeah, the collective is pretty cool. Right now I’m on sabbatical from the collective because I feel like I need to focus on my personal work.

CA: That’s what I wanted to know, are you able to keep these areas of your life separate or do they infiltrate one another?

BS: My own practise is difficult. iQhiya is demanding. There are eleven of us and we all have certain tasks. I couldn’t do it while I was in Switzerland, so I just took sabbatical and now that I’m back I need time to sort out my studio practise and what my plan is for next year because I am a working artist, I don’t have another job. This is what I do and I’m ok with that. That’s the choice that I made. So I just need to take a sabbatical from the collective until I feel comfortable with my practise again.

CA: We live in a patriarchal society, which is reflected in the art world. What has been the response to a collective that celebrates black female empowerment? Collectively are you stronger than individually?

BS: I don’t think so, I think there are really strong individuals and people will be surprised when we show individually. The thing is, they don’t give people a chance. That’s the main problem.

CA: Why do you think that is?

BS: I still don’t know. It has to do with the preservation of the white art world, and that’s ok, they can preserve the white art world, but this is Africa, things are going to happen regardless. So right now it’s fine. But iQhiya is coming out and the members are strong individually. Some of the members are not strong with their art, but they are strong with their words and people are getting to know themselves too. The collective, I think, there’s been some interest with collectors, but nothing serious. I don’t really think that matters, I think what matters is that you’re honest to the work, that you don’t betray the integrity of the work that you’re making. If you do that then what are you making art for? I wouldn’t buy an artist’s work who I feel is lying to me. You can try and lie, but you’re going to feel bad about it.

CA: Do you think female artists, or black female artists, are challenging the way we perceive art that is made by women? Are female artists actively breaking out of stereotypical categories of ‘female art production’?

BS: No. Not at all, I think a lot of women are falling into the trap. It’s still continuing, because they go to these institutions – and that is what needs to change first, the institution – but they go there and they are told, “you know, what would be interesting is if you did this or that”, because they haven’t seen any other woman do this. I remember taking photos of men together, when I was at art school and I was discouraged from making that work. Then Zanele Muholi came along. You know, they still push you to make work about identity; they try and push black kids into making stereotypical traditional art forms, especially females. They put you off, even in workshops, they used to tell me, “you can’t handle the welding machine, let me do it for you.” I was like, “no, just teach me how to use this thing, I’ll be fine.”

Installation view (detail) from Skattie Celebrates Buhlebezwe Siwani Ingxowa yeGqwirhakazi, 2016 (Exhibition at WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery, Cape Town).

CA: You are an isangoma as well as an artist, and you have previously spoken about how the two are inextricably linked. Do you think a Western audience is able to view your work from an objective point of view, or do you think there will always be a kind of fetishist fascination that comes from the pre-conceived notion of a sangoma as being a ‘witch doctor’?

BS: Of course, even here, it’s always going to be ‘witch doctor’ but you know, I’ve gotten to the point where I’m ok with it, just barely, because I understand that religion, spirituality has still got a long way to go in Africa. Getting rid of the Bible is going to take us forever, because it’s been around for centuries. Right now I’m ok with it, because I don’t fetishize myself. As long as I do that, I think I speak through the fetishism, through the work that I create.

CA: And the work that you did now in Switzerland, that is crossing over into ideas of the witch, how do you see the connection, or the disconnection, is there a parallel understanding do you think, to what we consider a herbal healer?

BS: Well, number one, I’m black, right, so there’s this extended thing, and I’m African. But no, a witch was just a sexually liberated woman. If you lived by yourself, or if you were a woman who didn’t necessarily want to get married, and this is how it started in the Middle Ages, the wives were worried that their husbands would want to go there, so they started accusing women of being witches. Or someone would get sick and she would get blamed, to get rid of her. There were also some who were actual gypsy healers who came from those lines.

CA: What are you working on now?

BS: I have the Skattie Celebrates exhibition opening on 17 November at WHATIFTHEWORLD, which will be on for a month.

CA: And you’re working with this soap moulded into bowls?

BS: Yes, some of the bowls will be very different; even as you see them now, things are subject to change very quickly because this is not the final work. It’s about washing and colonialism and it all stems from purification, from my masters body of work.

CA: And after that?

BS: I’m applying for my PhD. I don’t like to not know what I’m making work about. So even though I can be the authority on ubungoma, I need to back it up. I’m tired of Western philosophy constantly backing my work up, so I figured if people won’t write then I’m going to do my PhD and write about it myself.